Biography

From the introduction to the book: "Some of the most revealing chronicles of life during the Civil War came from the busiest people. Moreover, those who recorded lengthy observations tended to be well educated and farsighted. Judith Brockenbrough McGuire was in that relatively small class.

Her Diary of a Southern Refugee during the War is among the first such works published after the Civil War. The book initially appeared in 1867 and has been reprinted four times. It is one of the most quoted of memoirs written by a Confederate woman. Yet no historian has heretofore assumed the tasks of identifying scores of individuals mentioned by initials only, giving references for poems and quotations sprinkled throughout the text, or even providing an adequate summary of the Mrs. McGuire’s extraordinary life.

She came from solid Virginia stock. Brockenbroughs were principal settlers of Essex County, where the Rappahannock River widens toward its confluence with the Chesapeake Bay. Her father, William Brockenbrough (1778–1838), was a native of Tappahannock and graduate of the College of William and Mary. In 1802 he won election to the Virginia General Assembly. That began a long career as a Richmond attorney and judge. Eventually Brockenbrough became a member of the Virginia Court of Appeals. An acquaintance described the jurist as “a gentleman distinguished for the soundness of his legal knowledge and honored for the purity of his life, during a period when the old Commonwealth could point with becoming pride to the unsullied ermine of her judiciary.”

Brockenbrough married Judith Robinson White, whose King William County antecedents included a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a long line of Episcopal ministers. The family home, Westwood, was near Richmond in Hanover County. There, on March 19, 1813, the youngest daughter of the Brockenbroughs’ six children was born. Named for her mother, young Judith grew up among Richmond’s elite. A cousin, Dr. John Brockenbrough, had built a palatial downtown residence that became “the center of social life in the state capital.” (It later would become the White House of the Confederacy.) Such figures as John Marshall and Benjamin Watkins Leigh were regular dinner guests at the Brockenbrough home. Private tutors supplied the child with an excellent education. Judith’s knowledge of poetry and the great authors of literature are evident throughout her wartime diary.

After the death of her father in 1838, Judith lived at Westwood with her mother and younger brother, Dr. William S. R. Brockenbrough. The family was ardently Episcopalian, as was usually the case among Virginia aristocrats. That association led to a friendship between Judith and Rev. John Peyton McGuire.

Born in 1800, he was from a well-known Winchester family. His father had been an artillerist in the American Revolution. John McGuire was one of three brothers who entered the Episcopal ministry. In 1825 young McGuire assumed the rectorates of Saint Anne’s and South Farnham parishes in Essex County, neither of which had known a regular Episcopal priest for a quarter of a century. Methodists and Baptists had long dominated life in that area. McGuire borrowed their evangelic methods, organized missionary societies, and carried the faith to rich and poor alike. Through his devoted labors, one observer noted, “a dynamic pastor singlehandedly revived the Episcopal Church in Essex and much of the Rappahannock Valley.”

In 1827 Rev. McGuire married Mary Mercer Garnett. Her father was a former congressman and the largest landowner in the county. From that union came eight children, five of whom survived infancy: James, John P. Jr., Mary Mercer, Grace Fenton, and Emily. The unexpected death of their mother left the minister and his five young children bereft.

John McGuire’s close friendship with spinster Judith Brockenbrough led to marriage in November 1846, when he was forty-six, she thirty-three, and the minister’s children thirteen, ten, eight, seven, and six. For six years the new Mrs. McGuire devoted herself exclusively to caring for her new family. Judith McGuire never bore any children of her own, but she had a close, loving relationship with her stepchildren.

In the late 1840s, the ever-active priest opened a small school at Loretto in Essex County. McGuire’s English and Classical School emphasized a traditional curriculum focusing on proficiency in Latin and Greek. The headmaster introduced a new system of monitoring student performances by use of periodic report cards—a system American education in general later adopted. All the students lived at the pastor’s home, where they were “members of the family circle, and under a firm, vigilant, parental government.”

This educational venture was short lived, ending when Rev. McGuire accepted a call to become rector of the influential Christ Church in Alexandria. This too proved a short appointment, for in 1853 he agreed to become the third headmaster of the all-male Episcopal High School in Alexandria. The school was then attached as a diocesan academy to the Virginia Theological Seminary, the second-oldest Episcopal seminary in the nation.

McGuire began his new duties with seventy boys. The following year, eighty-two students were enrolled. Steady growth marked the high school’s progress thereafter. To the boys, Rev. McGuire was “Old Mac.” One wrote of the headmaster: “He was about five feet ten inches high, dressed in strictly clerical clothes. … His head was close set on a stout, robust body, and his every action was with vigor. … His face was kept scrupulously free of every sign of beard, his broad, high forehead was crowned with a thick suit of almost snow-white hair, and his penetrating eyes were always protected and aided by gold-rimmed spectacles.”

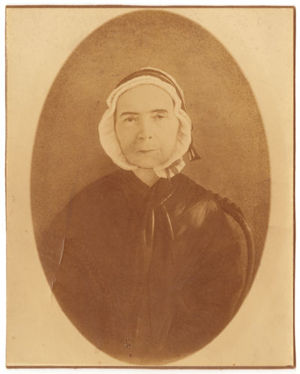

No word picture or portrait exists of Mrs. McGuire from that time. According to family lore, she was short and plump, with black hair pinned back tightly into a bun. She also had a drooping eye, a genetic trait of the Brockenbroughs. To the academy students, she was a second mother. “Her marvelous wisdom and goodness, gentleness and tact,” one recalled, “was the influence which softened the boarding school life to boys who had never before left home.”

The school historian was even more laudatory. “Mrs. McGuire was one of those women who came as near to divinity as mortal man can do in this world. The High School boys adored her; she was gentle, lovable and tender. … She reminded one of Matthew Arnold’s description of Mary, the mother of Christ: ‘If thou wouldst fetch a thousand pearls from the Arab Sea, one would gleam brightest, the best, the queenliest gem.’”

By 1861 the McGuires enjoyed a respected position in Alexandria society. Rev. McGuire was sixty-one and displaying signs of old age. His forty-eight-year-old wife remained active and enthusiastic. Judith McGuire responded to Virginia’s secession and the coming of war in typical womanly fashion. She spent days sewing and cooking for Virginia troops encamped at Alexandria; she faithfully attended services in the now half-empty college chapel; she cared for her flower bed, believing her flowers would bloom as usual and she would be there to see them. Nevertheless, she prudently prepared for any eventuality: she buried the family silver in the backyard and packed personal belongings in case she should be forced to leave home. Alexandria’s location directly across the Potomac River from Washington, combined with her husband’s known secessionist views, placed the family in uncertainty, if not danger.

On May 3, Rev. McGuire reluctantly closed the high school. Only thirteen students were left to pack their luggage and start home. Sons James and John were then drilling at a nearby camp; the three daughters were sent for safety to the home of their father’s sister in Clarke County near the Blue Ridge Mountains. When Rev. and Mrs. McGuire learned on May 25 that Union soldiers were crossing the river to occupy Alexandria, they abandoned their home and headed west across the Virginia piedmont. They would be among the first of tens of thousands of Civil War refugees.

Three weeks before leaving Alexandria, Mrs. McGuire began making entries in a diary. It offered an outlet for her turbulent emotions in a world so changed. As Mrs. McGuire was educated and possessed of a strong sense of history, the journal would also provide an invaluable record of events and observations as the family faced the indeterminable storm that lay ahead. The chronicle, in fact, is a riches-to-rags story illustrative of the Southern Confederacy.

For four years the McGuires lived a gypsy-like existence, moving thirty-four times in search of safety and stability. “Home” came to mean a temporary dwelling consisting of one to three rooms in someone else’s already-crowded residence.

The family stayed with in-laws in the Winchester area until Christmas Eve 1861, when Rev. and Mrs. McGuire and two daughters began a wintry trip to Mrs. McGuire’s home near Richmond. Lack of income forced the family to seek work in the satiated capital of the Confederacy.

Mrs. McGuire found this situation extremely painful. While her enfeebled husband sought employment, she went door-to-door in search of lodging. Rentals were scarce and expensive. Both husband and wife obtained minor jobs and endured the cramped atmosphere of their quarters. By the summer of 1862, Rev. McGuire’s health had worsened because of the unclean climate of Richmond. The couple spent six weeks with acquaintances in Charlottesville and Lynchburg and then returned to the capital.

Richmond was swollen to ten times its 1860 population. Eventually the McGuires found habitation in the village of Ashland, twelve miles north of the city astride the Richmond, Fredericksburg, & Potomac Railroad. The McGuires shared an eight-room home with three other families.

The sojourn in Ashland, which lasted ten months, was the only pleasant time the McGuires experienced in the war years. Husband and wife commuted to Richmond by rail: he toiling as a government clerk and serving as a hospital chaplain, she working as a clerk in the C.S. Commissary Department, making and selling soap, and devoting hours as a volunteer nurse in the small military hospital run by Sally Tompkins. It was also during the Ashland stay that Judith McGuire was witness to a military engagement.

August 1863 found the McGuires forced to return to Richmond. A quirk of fate then occurred: the family secured rooms in the Brockenbrough home where Judith had spent much of her growing years. She reentered the house with a combination of relief and humiliation. Here the McGuire family resided for the remainder of the war.

Mrs. McGuire was an indefatigable woman. She attended church regularly, cared for her ailing husband, walked the streets several times in search of temporary shelter, agonized over friends and loved ones, became one of history’s first female nurses, and did clerical work to bolster the family’s meager income in a wartime economy that saw inflation spiral 300 percent. (Her monthly wage of $ 125 as a clerk came at a time when a pair of boots cost $110, linen $12 per yard, a spool of thread or a package of pins $5—when such items were available, which they often were not.)

Throughout the war years, Mrs. McGuire made poignant entries in her diary. She wrote of travails, her many friends and acquaintances, and the multitude of activities of which she was a part and to which she was a witness. The journal was her sounding board for the strong emotions she felt and the horrors of war that she beheld. Her entries are a highly personal, revealing mixture of records of family activities, military reports and rumors, descriptions of conditions behind the battle lines, and her observations of life, her protestations of faith, and her fears and hopes for the future.

Three themes are consistent throughout her journal. First was the immense pride she had in her native land. A month into the war, she declared: “Our soldiers do not think of weakness. … Their hearts feel strong when they think of the justice of their cause. In that is our hope.” In 1863 she wrote: “It is grievous to think how much of Virginia is down-trodden and lying in ruins. The old State has bared her breast to the destroyer, and borne the brunt of battle for the good of the Confederacy.”

Second, she saw few redeeming qualities in Union soldiers. Commenting on their superior numbers pushing toward Richmond, Mrs. McGuire stated: “They come like the frogs, the flies, the locusts, and the rest of the vermin which infested the land of Egypt, to destroy our peace.” In rather unChristian fashion, she advocated the same total-war practices that Federal soldiers were exercising against the South. “I want the North to feel the war to its core,” she asserted, “and then it will end, and not before.”

The third characteristic fully evident throughout the diary is a religious faith that no ill fortune could blunt. Mrs. McGuire’s entries contain incisive commentaries on society, ruminations of past glories, and details of present hardships. Yet underneath it all is an unwavering dedication to the will of her Heavenly Father. At one low point, she wrote: “God will give us the fruits of the earth abundantly, as in days past, and if we are reduced, which I do not anticipate, to bread and water, we will bear it cheerfully, thank God, and take courage.”

Mrs. McGuire knew nothing about the intricacies of the battles in Virginia and adjacent states. She was far more concerned about the human casualties than of the strategic consequences of the engagements. Unlike Mary Chesnut’s well-known diary, Mrs. McGuire’s journal does not present views of the Confederate government, describe personality clashes between generals or politicians, or give opinions about the high levels of society.

Rather, Mrs. McGuire concentrated on class conflicts, the plight of the once-hads and the have-nots. She showed conclusively that those who had the least to gain from the war were the ones who suffered most. Her diary teems with the human, truly emotional episodes that are so often lost in the general rush of history. In fact, Mrs. McGuire often turned her journal into a collaborative narrative, as she frequently related the stories of others.

From her comes the tragedy of a Kentucky widow trying desperately to reach her wounded soldier-son in Virginia but encountering obstacle after obstacle in what proved to be a fruitless pilgrimage. Mrs. McGuire’s diary is the only source of an eyewitness account of the burial of Capt William Latane, the lone Confederate fatality in Gen. Jeb Stuart’s famous “Ride around McClellan” exploit. And very often she recounted what she knew of the lives of the sick and injured soldiers she nursed. Her comments are a far cry from the usual accepted picture of uniformed men marching gaily off to war. The few gaps in the diary are attributable mostly to personal fatigue. On one occasion, Mrs. McGuire apologized to herself, confessing: “After looking over commissary accounts for six hours in the day, and attending to home or hospital duties in the afternoon, I am too much wearied to write much at night.”

By 1865, when Mrs. McGuire was reduced to two meals a day, hearing weekly of the deaths of friends and family members, the diary entries assume the nature of a lengthy obituary of the Confederacy. Mrs. McGuire’s accounts of the evacuation and destruction of Richmond rank among the most detailed in Civil War history.

War’s end found the McGuires marooned among the rubble of the capital, with no home, no funds, no future. They never regained their antebellum prosperity. For a short time the couple took refuge at Westwood in nearby Hanover County. A cousin, Benjamin Blake Brockenbrough, and his wife, Ann Mason, invited the McGuires to move into the ancestral home at Tappahannock. This would be the final residence for the longtime refugees.

Rev. McGuire gave small parishes in Essex County as much priestly assistance as his declining health would permit. Judith spent late 1865 and early 1866 editing her diary for possible publication. She claimed to be releasing the record to the public at the insistence of her family. That was only partially true. It is highly likely that she ventured into the literary world for the first time because the family was in financial straits.

Her memory and her emotions were fresh as she reworked her diary. The easy flow of grammar and transition in the journal reflects how intently Mrs. McGuire labored on her entries. She expanded some passages into homilies; personal incidents appeared with lengthy conversation added; hindsight is visible here and there. Rarely was her memory guilty of factual error, in spite of her haste to submit the diary to a publisher. On the other hand, and like so many chroniclers of her time, Mrs. McGuire tactfully substituted initials or a blank space for the names of individuals mentioned. (Her broad range of family, in-laws, and friends made this practice an editorial nightmare.)

Shortly after settling in Tappahannock, the McGuires turned their home on the Rappahannock River into a girls’ school. The husband-wife teaching endeavor was short lived. Rev. McGuire died in 1869, hailed as the “Apostle of the Rappahannock” because of his lifetime of spiritual labors.

Mrs. McGuire had an active widowhood of twenty-eight years. Always meticulously dressed and formal in conduct, she possessed what one acquaintance considered “an air of grandeur.” In addition to running the school with assistance from local volunteers, she completed and published in 1873 a small, eulogistic biography of Gen. Robert E. Lee for her students. Much of the text consisted of undocumented quotations and sermonic texts, quite in keeping with Southern emotions accompanying the general’s death. Mrs. McGuire donated all royalties to St. John’s Episcopal Parish in Tappahannock. Indeed, she was charitable in many ways. When Mrs. McGuire discovered a pair of George Washington’s spurs at the Brockenbrough family home, she promptly gave them to the museum at Mount Vernon.

Death came March 21, 1897, two days after her eighty-fourth birthday. She was buried beside her husband in St. John’s Church cemetery. For years the remains lay inside an “iron-railed, vine-covered, but unmarked grave.” The gravesites underwent complete renovation in the 1970s. Two large stone slabs now denote the resting places. Mrs. McGuire’s marker cites her authorship of Diary of a Southern Refugee. However, for an epitaph, she would have much preferred the biblical quotation: “Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth: Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labours; and their works do follow them.”

Sources

- Book: McGuire, Judith White - Diary of a Southern Refugee During the War, by a Lady of Virginia. [1]

It may be possible to confirm family relationships with Judith by comparing test results with other carriers of her ancestors' mitochondrial DNA. However, there are no known mtDNA test-takers in her direct maternal line. It is likely that these autosomal DNA test-takers will share some percentage of DNA with Judith:

-

~1.56%

~6.25%

Brookes McKenzie

~6.25%

Brookes McKenzie  :

23andMe, GEDmatch DU705840C1 [compare]

+

AncestryDNA, Ancestry member McKenzie_Brookes

+

Family Tree DNA Family Finder, GEDmatch T867865 [compare], FTDNA kit #197129

:

23andMe, GEDmatch DU705840C1 [compare]

+

AncestryDNA, Ancestry member McKenzie_Brookes

+

Family Tree DNA Family Finder, GEDmatch T867865 [compare], FTDNA kit #197129

-

~0.39%

Rodney Welch

:

23andMe

:

23andMe

Have you taken a DNA test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Featured National Park champion connections: Judith is 12 degrees from Theodore Roosevelt, 19 degrees from Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, 15 degrees from George Catlin, 11 degrees from Marjory Douglas, 20 degrees from Sueko Embrey, 14 degrees from George Grinnell, 22 degrees from Anton Kröller, 17 degrees from Stephen Mather, 21 degrees from Kara McKean, 15 degrees from John Muir, 14 degrees from Victoria Hanover and 22 degrees from Charles Young on our single family tree. Login to find your connection.

B > Brockenbrough | M > McGuire > Judith Robinson (Brockenbrough) McGuire