| Illustrious Men William Marshal was one of 16 Illustrious Men, counselors to King John, who were listed in the preamble to Magna Carta. Join: Magna Carta Project Discuss: magna_carta |

Contents |

Biography

Birth and Parentage

William was the son of John Marshal and Sybil, daughter of Walter de Salisbury.[1][2] He was probably born in late 1146 or early 1147.[1][2] His birthplace is unknown - see the Research Notes.

Earlier Life

In 1152, during the siege of Newbury, Berkshire, his father handed him over to King Stephen as a hostage. His father broke the terms of his agreement with Stephen, who expected the surrender of Newbury Castle, but William's life was spared.[1] King Stephen is said to have played in his tent with William[2] instead of, as threatened, catapulting William over the battlements into Newbury Castle.[3] The story goes that William's father, threatened with the death of his hostage son, responded that he had the anvils and hammers to make a finer one.[1]

Subsequently, William was a squire of William de Tancarville, Master Chamberlain of Normandy, for eight years.[1][2] He was a younger son, and had to a great extent to make his own way initially, which he did as a warrior and participant in tournaments.[1][4] He was probably knighted in 1166 and was almost immediately involved in a frontier war.[1]

In 1168 he went with his uncle Patrick, Earl of Salisbury to Poitou, where Patrick was killed and William was captured by the forces of Guy de Lusignan. He was ransomed by Eleanor of Aquitaine and returned to England.[1][2] Eleanor made him a member of her household.[5]

Henry the Young King

In 1170 William Marshal went on to join the household of Henry the Young King[1][2] whom he trained in arms and chivalry.[1][6] In 1173 he supported the Young King in his rebellion. In 1174 he was a witness to the subsequent agreement between Henry II and his children.[1][2]

William's relationship with the Young King and the rewards from his participation in tournaments gave him financial independence and the resources to maintain a household of knights.[1]

The Young King had made a vow to go on crusade, but died in 1183. On his deathbed, he asked William to crusade in his place. This William did[2], after escorting the remains of Henry the Young King to Rouen.[1]

Last Years of Henry II

William was back in Normandy, possibly by the spring of 1186, and became a member of Henry II's household.[1] He took part in the fighting in the next two years against the future King Richard I.[2] In Henry II's last months he was a commander of the king's household guard, was in command of the rearguard when Henry II escaped from Le Mans to Angers in 1189. The story goes that in rearguard action against the future Richard I, he had Richard at his mercy and spared his life, killing his horse instead.[1] He attended Henry II's deathbed at Chinon and escorted the king's corpse to Fontevraud.[2]

Marriage and Children

William Marshal retained royal favour on the accession of Richard I, who gave him as wife Isabel de Clare.[2] Their marriage took place in July or August 1189.[1] in London[2] where she lived in the Tower (for her protection against abduction and a forced marriage). The marriage made him a very wealthy lord, with lands and claims to lands in England, Wales, Ireland and Normandy.[1][4] Through his wife he assumed the title Earl of Strigoil.[2]

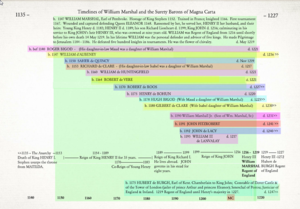

William and Isabel had ten children - five sons and five daughters - who lived to adulthood, but none of his sons had any legitimate heirs.

- William Marshal, 2nd/5th Earl of Pembroke[1][7]

- Richard Marshal, 3rd/6th Earl of Pembroke[1][8]

- Gilbert (Knight Templar), 4th/7th Earl of Pembroke[1][9]

- Walter, 5th/8th Earl of Pembroke[1][10]

- Anselm, 6th/9th Earl of Pembroke[1][11]

- Isabel, who married Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and Hertford, and Richard, Earl of Cornwall[1]

- Eva, who married William de Braose, Baron Abergavenny[1]

- Sibyl, who married William de Ferrers, Earl of Derby[1]

- Joan, who married Warin de Munchensy[1]

- Maud or Matilda, who married Hugh Bigod Earl of Norfolk and William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey[1]

Reign of Richard I

At Richard I's coronation on 3 September 1189, William carried the gold sceptre and cross, and indication of the favour in which he was held.[1][2] Soon after he was made a justiciar under William de Longchamp, Chief Justiciar of England.[2] When Walter de Coutances, Archbishop of Rouen became Chief Justiciar in the autumn of 1191, William was his main assistant.[1][2]

In 1189 he was granted Pembroke Castle, which he began to turn from an edifice of wood and earth into a stone fortification.[12]

In about 1190 he added considerably to his estates by acquiring a moiety of the lands of Walter Giffard, former Earl of Buckingham, thereby becoming Lord of Longueville.[1][2]

In 1193 the future King John rebelled against his brother: William Marshal stayed loyal to the king and captured Windsor Castle[1][2] but declined to do homage to Richard I for his Irish lands, saying the homage was owed to John.[1] That year he was made Sheriff of Sussex.[13]

In March 1193/4 he inherited the title of Marshal of England from his brother John[2], who was killed fighting on the side of the future King John against forces loyal to Richard I.[4]

William spent most of the years from 1194 to 1199 in Normandy and Northern France.[1][2] As he was dying in 1199, Richard I appointed him custodian of Rouen and the royal treasure there.[1][2]

Reign of King John

William Marshal helped to secure the smooth accession of King John in 1199[1][2], and was present at the coronation on 27 May 1199.[2] King John granted him the title and estates of Earl of Pembroke which his wife's father had had, but had been deprived of by Henry II in 1154.[1][2][4][14]

From 1198/9 to 1206/7 he was Sheriff of Gloucestershire.[13][15]

He served King John in Gascony, England, and Normandy, and fought for him in Wales.[2] In 1202 he was made Constable of the castle of Lillebonne in Normandy.[2] In 1203 his forces were defeated when he tried to relieve the castle of Chateau Gaillard in Normandy. Soon after that, he accompanied King John to England.[1]

King John's loss of Normandy threatened William's possession of his estates there. John sought to give him some compensation with lands in England, but William entered into negotiations with Philippe-Auguste, leading to his paying the French king homage for his Normandy possessions in 1205. This led to his falling temporarily into John's displeasure, exacerbated when William Marshal refused to join in a planned expedition to Poitou.[1] At one point King John sought to have him arraigned for treason, but other peers refused.[1] John also tried to get one of his household knights to challenge William Marshal, but nobody was willing to do so.[1]

Between 1207 and 1213 William was mainly in Ireland, effectively in exile.[2] King John deprived him of some of his offices, and some of William's supporters abandoned him.[1] William sought to build bridges with John in 1212, when he clearly sided with the king at a time of threatened baronial conspiracy.[1] In 1213 William was summoned back to England, where lands that had been confiscated were returned to him and he was given additional lordships.[1] He was a witness to King John's act of submission to the Pope.[2] The king entrusted him with castles in Wales and Ireland.[2]

In 1215 William Marshal was one of the Illustrious Men listed as King John's counsellors in the Magna Carta.[2][16][17] He stayed loyal to the king and when civil war broke out, he secured the Welsh Marches.[1] He oversaw King John's funeral at Worcester[1] and was one of the executors of his will.[1][2]

Final Years

William was present for the third time at a coronation when Henry III was crowned in 1216.[2] In November that year he was chosen as Regent, a position he held until his death.[1][2]

The next year, at the age of about 70, he commanded the royal forces in their victory over rebels and the French in the Battle of Lincoln, taking an active part in the fighting.[1][2] In September 1217 he concluded a peace treaty with the French.[1][2] An agreement with Llywelyn of Gwynedd followed in March 1218.[1]

Death

William died in May 1219.[1][2] On his deathbed he committed Henry III to the care of the Papal legate[1][2], and also was formally made a member of the Knights Templar in fulfilment of a vow made on crusade.[4][18] He died at Caversham, Berkshire on 14 May 1219[1][14] and was buried in the round chapel of the Knights Templar in what is now the Temple, London.[1][14]

His son William commissioned an adulatory verse biography of him - L'Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal - soon after his death.[19]

Research Notes

Earl of Pembroke

In William's lifetime, no one actually called him 'the 4th Earl of Pembroke' nor did they call him 'the 1st Earl of Pembroke' - "re-created" or otherwise. He was simply the Earl of Pembroke. Whether The Marshal was the 4th or the 1st of Pembroke is a distinction which scholars of modern time debate. Isabel de Clare's father, Gilbert de Clare (Strongbow) was Earl of Pembroke. After her brother died, Isabel became Countess of Pembroke.

William's Birth Date or Location is Unknown

It is doubtful that William was born at Pembroke, which he obtained through his wife's inheritance later in his life, not from William's father. It is doubtful he was born in France, while his father was fighting Earl Patrick and King Stephen for his castles in England. It is likely he was born in England, but it is not stated in a known record.

What was a 'Marshal'?

"Marshal" originally referred to a function of "horse servant", which is what the word meant in the old language of the Franks. By William's lifetime, the work of the king's Marshal had grown far away from its original tasks. There were thus many marshals, but William's family held the highest marshalcy in the royal household. The office became hereditary in the time of William's father.[20][21]

Duties of the Master Marshall "involved the keeping of certain royal records" and the management of "four other lesser marshals, both clerks and knights, assistants called sergeants, the knight ushers and common ushers of the royal hall, the usher of the king's chamber, the watchmen of court, the tent-keeper and the keeper of the king's hearth".[22][23]

Even before he inherited the office William was apparently referred to as "the Marshal" (li Mareschal in the French of the time). By the time William died, all of Europe referred to him this way, and he had given the position a new status, leading in later generations to the peerage title of "Earl Marshall", something William had sometimes been called (comes mareschallus in Latin).[20][14][24]

Sources

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 1.39 1.40 1.41 1.42 1.43 1.44 1.45 1.46 1.47 1.48 1.49 1.50 1.51 1.52 1.53 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry for 'Marshal, William [called the Marshal], fourth earl of Pembroke (c. 1146–1219)', print and online 2004, available online via some libraries

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 2.33 2.34 2.35 2.36 G E Cokayne. Complete Peerage, new edition, Vol. X, St Catherine Press, 1945, pp. 358-264, PEMBROKE IV

- ↑ David Carpenter. The Struggle for Mastery (The Penguin History of Britain 1066-1284), Penguin Books 2004, p. 188

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Wikipedia: William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke

- ↑ D Crouch. William Marshal: Knighthood, War and Chivalry, 1147- 1219. GB: Pearson Education Ltd, 1990 (reprinted 2002), p. 30

- ↑ C A Armstrong. William Marshal Earl of Pembroke, Kennesaw, GA: Seneschal Press, 2006, pp.90, 100, 135 - 141

- ↑ G E Cokayne, Complete Peerage, Vol. X, pp. 365-368

- ↑ G E Cokayne, Complete Peerage, Vol. X, pp. 368-371

- ↑ G E Cokayne, Complete Peerage, Vol. X, pp. 371-374

- ↑ G E Cokayne, Complete Peerage, Vol. X, pp. 374-376

- ↑ G E Cokayne, Complete Peerage, Vol. X, pp. 376-377

- ↑ Wikipedia: Pembroke Castle

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Richardson, Douglas (2013). Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 5 vols., ed. Kimball G. Everingham (Salt Lake City, Utah: the author, 2013), Volume IV, pp. 40ff

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 C Cawley. Medieval Lands v.3, 2006, entry for 'William Marshal son of John FitzGilbert'

- ↑ Wikipedia: High Sheriff of Gloucestershire]

- ↑ Preface to the Magna Carta (The Magna Carta Project website)

- ↑ Douglas Richardson. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 4 vols, ed. Kimball G. Everingham. 2nd edition. Salt Lake City: the author, 2011, p. 8. See also WikiTree's source page for ‘’Magna Carta Ancestry.’’

- ↑ Sydney Painter. William Marshal Knight-Errant, Baron and Regent of England, Canada: Medieval Academy of America, Johns Hopkins Press, 1933, reissued 1982, reprinted 2001, pp. 56 and 284

- ↑ Wikipedia: L'Histoire de Guillaume le Marechal

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Wikipedia: Earl Marshal

- ↑ Wikipedia: John Marshal (Marshal of England)

- ↑ D Crouch, William Marshal: Knighthood, War and Chivalry 1147-1219

- ↑ From a treatise of 1136 made for King Stephen, describing the duties of the Marshal.

- ↑ Round, J. H. (1911), The King's Serjeants & Officers of State with their Coronation Services. https://archive.org/stream/kingsserjeantsof00rounuoft#page/88/mode/2up

- Preface to the Magna Carta (The Magna Carta Project website, accessed 1 October 2019)

- The Magna Carta Project: website page for William Marshal. Witness to numerous charters of King John, and his 1200 will approved by King John. Accessed 1 October 2019.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry for 'Marshal, William [called the Marshal], fourth earl of Pembroke (c. 1146–1219)', print and online 2004, available online via some libraries

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, entry for 'Marshal, William (d.1219)', Wikisource

- Cokayne, G E. Complete Peerage, new edition, Vol. X, St Catherine Press, 1945, pp. pp. 358-264, PEMBROKE IV

- Nicolas, Nicholas Harris. Testamenta Vetusta (Nichols & Son, London, 1826) Vol. 1, Page 47

- Cawley, C. (2006). Medieval Lands v.3, entry for 'William Marshal son of John FitzGilbert'

- Richardson, Douglas (2013). Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 5 vols., ed. Kimball G. Everingham (Salt Lake City, Utah: the author, 2013), Volume IV, pages 40-47

- Armstrong, C. A. William Marshal Earl of Pembroke. (Kennesaw, GA: Seneschal Press, 2006). Includes his years in Ireland and the lives of all the daughters of William Marshal.

- Asbridge, Thomas. The Greatest Knight: The Remarkable Life of William Marshal, the Power Behind Five English Thrones, Simon & Schuster, 2015

- Buck, J.O. (n.d.). Pedigrees of Some of Emperor Charlemagne's Descendants", Vol. II.

- Crouch, D. (1990 rp 2002). William Marshal: Knighthood, War and Chivalry, 1147- 1219. GB: Pearson Education Ltd.

- Duby, G. (1985), trans. Howard, Richard. William Marshal The Flower of Chivalry, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Painter, Sydney. William Marshal Knight-Errant, Baron and Regent of England Canada: Medieval Academy of America, (1933 Johns Hopkins Press) (reissued 1982, reprinted 2001)

- Johnson, Ben (undated). William Marshall, A Knight’s tale

- Wikipedia: William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke

- Fenton, Richard. A Historical Tour Through Pembrokeshire (Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Co., 1811) Page 379-80.

- "Richard the First,... gave Isabella in marriage to William de la Grace, who thereupon became Earl of Pembroke, was created Earl Marshal of England, and ever after bore the name of Marshal... He died after being earl thirty years, leaving fives sons who were all earls in succession. He was buried in the Temple Church with the following epitaph: Sum Quem Saturnum Sibi Sensit Hibernia, Solem Anglia, Mercurium Normannia, Gallia Martem."

- Historian Richard Abels, in "Practical Chivalry in the 12th Century: The Case of William Marshal" (2012), calls Marshal "among the most extraordinary individuals in medieval English history. Eulogized by Archbishop Stephen Langton as "the best knight in the world" and by King Philip Augustus of France as "the most loyal man" he had ever known". Prof. Abels wrote the 29-page essay as required reading for his course "The Age of Chivalry and Faith" at the U.S. Naval Academy. Available online here:

No known carriers of William's DNA have taken a DNA test.

Have you taken a DNA test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Rejected matches › William Marshall (abt.1877-) › William Preston Marshall › William Preston Marshall › Charles W. Marshall › John William Marshall › Ronald W. Marshall › William Elmo Marshall (abt.1914-1979) › William Henry Marshall (1770-abt.1834) › William Marshall (1858-1936) › William Marshall (abt.1820-) › William Marshall (abt.1760-) › William Marshall (abt.1838-) › William Marshal (-aft.1843) › William Thomas England (1787-abt.1852) › William Marshal (abt.1710-) › William Marshall Boyd Jr. (abt.1916-abt.1993) › William Marshall Bever (1890-1966) › William Marshall Coursen (abt.1830-) › William Marshall Frazier (abt.1866-1958) › William Marshall Grose (abt.1815-1890)

Featured Foodie Connections: William is 27 degrees from Emeril Lagasse, 27 degrees from Nigella Lawson, 26 degrees from Maggie Beer, 41 degrees from Mary Hunnings, 33 degrees from Joop Braakhekke, 32 degrees from Michael Chow, 29 degrees from Ree Drummond, 27 degrees from Paul Hollywood, 27 degrees from Matty Matheson, 29 degrees from Martha Stewart, 33 degrees from Danny Trejo and 33 degrees from Molly Yeh on our single family tree. Login to find your connection.

https://youtu.be/cTjQp_T Thank you!

edited by Clare Bromley III

If this isn't already in his Sources, it should be.

edited by Keith Mann Spencer

This makes Richard's father Gilbert the 1st Earl of Pembroke, Richard the 2nd, Gilbert the 3rd & Isabel's husband William Marshal the 4th. So I'm not sure where 5th comes from for this profile.

Cheers, Liz

Any objections to making that change?? Douglas Richardson apparently refers to him as Earl of Pembroke without a number.