Biography

Roman Peter Pautler (1917-1945)

Roman Pautler was the grandson of Christine Nuwer Pautler—the youngest child of John Nuwer and Catherine Kieffer. He was born June 10, 1917 in the Village of Lancaster. The only boy in the family, he was one of five children born to Peter Pautler and Clara Anstett. His mother died in 1919 when Roman was only two years old. The 1920 and 1930 Censuses found Peter Pautler and his children living at Christine Nuwer Pautler’s residence in the Village of Lancaster.

Roman Pautler attended school in Lancaster and, at the age of 15, after completing one year of high school, he began working a blue-collar job. The 1940 Census found Roman and his father working at the Magnus Metal Co. which was one of the railroad-related factories located in Depew. Roman worked as a semiskilled grinder and polisher. Both Peter and Roman were still living in the Village with Christine Nuwer Pautler.

Roman Pautler married Helen Roll on August 16, 1941. She was the daughter of William Roll and Ester Pickard. Helen Roll’s grandparents were Joseph Roll and Mary A. Staebell who operated the Cayuga House hotel in Depew from 1888 to 1902.

It was only four months after Roman Pautler and Helen Roll were married that the United States entered World War Two. War was declared on December 8, 1941. Almost a year later, on November 7, 1942, Roman Pautler enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was 25 years old and had been married a bit less than 15 months. His enlistment documents, however, state that he was separated from his wife at that time.

Roman Pautler’s assignment for the next two years is not well documented. We know he was stationed with the 89th Infantry Division in 1945 and he may have been assigned to that unit shortly after his enlistment. The 89th Infantry Division was activated in June 1942 and was deployed to the European Theater in December 1944. The only document identifying Roman Pautler in this time frame was a February 1944 hospitalization for a “trivial wound,” but the location of the hospital was not recorded.

In 1942 the 89th Division was stationed five miles south of Colorado Springs at Camp Carson, Colorado. It received its full quota of personnel, over 13,000 men, by January 1943. Throughout that year, the unit trained for combat and engaged in field exercise. In the autumn of 1943 and again in the winter of 1944, the 89th Division participated in combined maneuvers where military scientists tested field tactics, experimented with equipment, and explored alternative means of transportation. The first set of maneuvers were conducted in Louisiana and the second in California.

In May 1944 the division sent 2,700 men to the European Theater and moved its headquarters to Camp Butner, North Carolina. In the following months the division took on new men and engaged in their training. Then, in November, the 89th Infantry Division was alerted that it would ship as a unit to the European Theater. In December the entire division, with all its equipment, was moved by train from North Carolina to a camp near Boston Massachusetts. On January 10, “a clear, cold morning,” the entire division boarded five troop transport ships and left Boston harbor.

Roman Paulter’s unit, the 354th regiment, was on the Edmund B Alexander along with the division commander and his staff. There were over 5,400 men packed abroad the convoy flagship. The following description of the voyage was provided by one of the solders.

- Life on board was necessarily cramped. There was room for every man, none to spare. Canvas and iron bunks were staked five and six high, with just enough room for each man between, with his pack, blanket roll, duffle bag, helmet, gas mask and rifle. Routine was strict: troops were allowed on deck only at certain times, and after dark smoking was permitted only in the latrines. Because of the huge number of men using limited facilities, only two meals were served daily.

The original orders had called for the 89th Division to disembark in England and complete their training objectives. But the Battle of the Bulge (Dec 16, 1944 - Jan 25, 1945) changed those plans and the 89th Division was directed to land in France.

Roman Pautler’s unit moved into the European theater during the closing days of the Battle of Budge. The division began landing in France on January 21, 1945. The transport ships anchored near the Port of Le Havre. This was the same port where many of Roman Pautler’s ancestors embarked for America on sailing ships one hundred years earlier.

In 1945 the unloading facilities at Le Havre had been thoroughly blasted by Allied bombers, and, to get ashore, it was necessary to transfer the troops to smaller landing crafts. Accounts by solders of the 89th Division describe the challenges of getting ashore in the winter at docks that were in various stages of destruction. The troops had to climb down rope ladders to the landing crafts and the landing was conducted in the “pitch dark” of night. While waiting for landing crafts on the decks of their transport ships, the troops were “weakened by the cold” and many by “hunger as the result of seasickness.”

After arriving on land, the solders again waited many hours for trucks that would transport them forty-mile to their next camp. One veteran of the unit recalled that the trucks were “completely open to the near-zero weather and we were packed into them.... As the trucks gained speed, chill winds penetrated to the bone.” The veteran continued, “at the destination some GIs lined up for coffee but most, frozen and exhausted, simple unrolled blankets on the snow where they stood. The tents were almost all either blown down or never put up. It was a miserable time for 89ers.”

The 89th Division remained at this camp during the month of February, and at the beginning of March received orders to move into Luxembourg in preparation for going into battle. The first units moved on March 3rd. Some troops loaded into “ancient freight cars,” others into trucks. “The trip averaged over three hundred miles and blown bridges, ruined roads and detours delayed trucks frequently.” By March 8, the entire division had arrived at its designated area. The 89th Division had been assigned to XII Corps of the U.S. Third Army which was under the command of General George S. Patton, Jr.

|

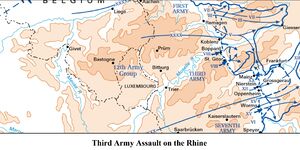

Following the Battle of Bulge, allied forces in Europe entered the Rhineland Offensive, which was a series of operations aimed at occupying the Rhineland and securing passage over the Rhine river. The U.S. Third Army was involved with Operation Lumberjack. The plan called for the U.S. First Army to attack toward the juncture of the Ahr and Rhine Rivers and then to meet the U.S. Third Army. General Patton’s forces would capture the Eifel Mountains and then the Mosel Valley, trapping the remainder of the German Seventh Army in the Eifel area. If successful, Lumberjack would capture Cologne, secure the Koblenz sector, and bring the two Armies to the western shore of the Rhine River.

The 89th Division was committed to this operation on March 12. The battleground ahead was the forested Eifel highland. The assignment involved (a) clearing and securing towns of enemy machine-gun nests and snipers, and (b) opening supply routes as German engineers were blowing bridges and felling trees to block the roads.

On March 16, the 89th Division was tasked to establish a bridgehead across the Moselle River. This assignment was intended to open a vital supply route over the river and to protect the XII Corps’ right flank. On the evening of March 16th, assault boats were unloaded from trucks and concealed along the waterfront.

At 3:30 a.m., March 17, the first riflemen climbed into the boats and silently paddled across the river, which was about two hundred yards wide. The initial three waves crossed at one-hour intervals; first riflemen, followed by heavy weapons and then antitank crews. Roman Pautler’s regiment, the 354th, went over without drawing a shot, while the 353rd received only light sniper fire. By dawn, rafts were ferrying vehicles across the river. By the end of the day, engineers had competed a span and heavy traffic was moving across. Meanwhile the Division infantry cleared towns and villages thirteen miles beyond the Moselle bridgehead.

Crossing the Rhine river was the next objective. The original plan called for the 89th Division to cross the Rhine with the Third Army’s main force south of Mainz, but this assignment was given instead to the 5th Division. On March 23, the 89th was transferred to the Third Army’s VIII Corps.

|

“The location of the Rhine river-crossing was critical,” explained an Army strategist. “General Patton knew that the most obvious place to jump the river was at Mainz or just downstream, north of the city. The choice was obvious because the Main River ... empties into the Rhine at Mainz and an advance south of the city would involve crossing two rivers rather than one. However, Patton also realized that the Germans were aware of this difficulty and would expect his attack north of Mainz. Thus, he decided to feint at Mainz while making his real effort at Nierstein and Oppenheim, 9 to 10 miles south of the city. Following this primary assault, which the XII Corps would undertake, the VIII Corps would execute supporting crossings at Boppard and St. Goar, 25 to 30 miles northwest of Mainz.”

On March 22, with a bright moon lighting the sky, elements of the XII Corps’ 5th Infantry Division began the Third Army’s Rhine crossing. Two more Third Army crossings, both by the VIII Corps, followed. In the early morning hours of March 25, the 87th Infantry Division crossed the Rhine to the north at Boppard, and then twenty-four hours later the 89th Infantry Division crossed 8 miles south of Boppard at St. Goar. The defense of these sites was more determined than that which the XII Corps had faced.

The 89th Division attacked at 2 a.m. on March 26. Two regiments, the 354th and 353rd, made the assault while the 355th was held in reserve. The 354th Infantry Regiment attacked from St. Goar. The 1st Battalion attacked towards Wellmich and the 2nd (Roman Pautler’s unit) towards St. Goarshausen. Both attacks met strong resistance. The crossing by the 2nd battalion was described as follows.

- It’s first wave (E and F Companies) attacked across the river from St. Goar at 0200, directly at the town of St. Goarshausen, a natural fortification. The river is about 300 yards wide here. On the trip across they met point-blank, grazing fire just above the water from machine guns and 20 mm antiaircraft weapons. The defenders had ignited a number of river barges on the St. Goarshausen side, thus lighting up the river clearly and the vulnerable assault boats on it. Also, German artillery, mortar, and 88 mm fire, fell on the west shore. There were no friendly artillery preparations for the attack was planned as a surprise. To this day, survivors recall this scene as one from hell.

- 2nd Battalion [Pautler’s unit] took casualties. Assault boats were smashed and sank, and numbers of men were killed, wounded, or missing. More than a few were lost in the turbulent current. Survivors were lucky: many swam ashore or were picked up by other boats. The surprise is that so many men made it—getting ashore with their helmets, rifles, and ammunition. Troops waiting to cross were driven behind walls and houses at St. Goar by the fire as they tried to deploy on the riverbank. Radio communications failed with the first wave on the east side, and only restored (with E Company) about 0430 that morning. The first wave of 2nd Battalion was cut off until well into the morning.

Despite the terrain, enemy machine-guns, and 20-mm antiaircraft guns, VIII Corps troops managed to gain control of the east bank, and by dark on the 26th, with German resistance crumbling all along the Rhine, the American soldiers were preparing to continue their drive the next morning.

Roman P. Pautler, however, was killed in action on the Rhine river while crossing from St. Goar to St. Goarhausen. He was a member of the company headquarters and in the assault boat with the Commander of Company E and the First Sergeant. A 20-mm antiaircraft shell exploded in the boat, killing all but one of the occupants. His hospital admission record simply stated: “Battle casualty; killed in action; location unknown.”

Roman Pautler was buried at the American Cemetery in Luxembourg City, Luxembourg. This cemetery had been established in December 1944 by the U.S. Third Army. There are 5,070 service members buried at the cemetery, most of them lost their lives in the Battle of the Bulge or in the advance to the Rhine River. The cemetery is also the final resting place of General George S. Patton, Jr.

Back in Buffalo, the Evening News reported Roman Pautler’s death on May 16, 1945.

- One of the soldiers who gave their lives to make victory possible in Germany was Pfc. Roman P. Pautler of 27 St. Joseph St., Lancaster, who was killed in Germany March 26. He is survived by his father, Peter Pautler of the St. Joseph St. address, and four sisters, Miss Margaret Pautler, Mrs. George Smith, Mrs. William Ott, and Mrs. Donald Thomas. A memorial mass was sung in St. Mary’s Church, Lancaster at 8 o’clock Tuesday.

|

Bibliography

- 89th Infantry Division of World War II,

https://89infdivww2.org/index.htm - 89th Infantry Division - Rolling W,

https://www.armydivs.com/89th-infantry-division - 89th Infantry Division (United States),

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/89th_Infantry_Division_(United_States) - The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II: Rhineland

https://history.army.mil/brochures/rhineland/rhineland.htm - The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II: Central Europe

https://history.army.mil/brochures/centeur/centeur.htm - Operation Lumberjack

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Lumberjack - Luxembourg American Cemetery

https://www.abmc.gov/Luxembourg - Memorial to Roman P. Pautler

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56062887/roman-p-pautler

Roman served as a Private First Class, 354th Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division, U.S. Army during World War II.

He resided in Erie County, New York prior to the war.

He enlisted in the Army on November 7, 1942 in Buffalo, New York. He was noted as being employed as a filer, grinder, buffer, and polisher of metal and also as Separated, without dependents.

Roman was "Killed In Action" during the war and was awarded a Purple Heart.

Service # 32580976

Sources

- Roman Peter Pautler (1917-1945) by Michael Nuwer, May 2021, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Alb_uLrLe9KS51A5-mXW9ac6YeA6qExn/edit?fbclid=IwAR1kHlzY6MUnCTwxe705adj6s8ote84xA-eyJVdyw7jS0FCXRqATeOX6pIk

- 1920 United States Census, Lancaster, Erie, New York, United States

- 1940 United States Census, Ward 3, Lancaster, Lancaster Town, Erie, New York, United States

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56062887

It may be possible to confirm family relationships with Roman by comparing test results with other carriers of his ancestors' Y-chromosome or mitochondrial DNA. However, there are no known yDNA or mtDNA test-takers in his direct paternal or maternal line. It is likely that these autosomal DNA test-takers will share some percentage of DNA with Roman:

-

~0.78%

Mark Hallenbeck

:

AncestryDNA, GEDmatch TS9241393 [compare], Ancestry member mhallenbeck56

:

AncestryDNA, GEDmatch TS9241393 [compare], Ancestry member mhallenbeck56

Have you taken a DNA test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Featured National Park champion connections: Roman is 20 degrees from Theodore Roosevelt, 25 degrees from Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, 20 degrees from George Catlin, 23 degrees from Marjory Douglas, 29 degrees from Sueko Embrey, 20 degrees from George Grinnell, 29 degrees from Anton Kröller, 21 degrees from Stephen Mather, 23 degrees from Kara McKean, 21 degrees from John Muir, 22 degrees from Victoria Hanover and 32 degrees from Charles Young on our single family tree. Login to find your connection.