Biography

John Penn (14 July 1729 – 9 February 1795) was the last governor of colonial Pennsylvania, serving in that office from 1763 to 1771 and from 1773 to 1776. Educated in Britain and Switzerland, he was also one of the Penn family proprietors of the Province of Pennsylvania from 1771 until 1776, holding a one-fourth share, when the creation of the independent Commonwealth of Pennsylvania during the American Revolution removed the Penn family from power.

Held in exile in New Jersey after the British occupation of Philadelphia, Penn and his wife returned to the city in July 1778, following the British evacuation. After the war, the unsold lands of the proprietorship were confiscated by the new state government, but it provided Penn and his cousin, John Penn "of Stoke", who held three-fourths of the proprietorship, with compensation. They both appealed as well to Parliament, which granted them more compensation.

Contents [hide] 1 Early life and education 1.1 Marriage (1)

2 Immigration to Pennsylvania 3 Governorship 3.1 Marriage (2) and family 3.2 Second appointment as governor

4 Revolution and after 5 See also 6 Notes 7 References 8 External links

Early life and education[edit]

John Penn was born in London, the eldest son of Richard Penn and Hannah Lardner. His father Richard had inherited a one-fourth interest in the Pennsylvania proprietorship from his father, the Pennsylvania founder William Penn. It provided the family a fairly comfortable living. Richard's older brother Thomas Penn controlled the other three-fourths of the proprietorship. As Thomas did not have any sons while John Penn was in his youth, the younger man was in line to inherit the entire proprietorship (one-fourth from his father and three-fourths from his paternal uncle). John Penn's upbringing and conduct was of concern to the entire family.

Marriage (1)[edit]

In 1747, when John Penn was eighteen years old and still in school, he secretly married Grace Cox, a daughter of Dr. James Cox of London.[1] The Penn family disapproved of the marriage, believing that Cox had married Penn to share in the family fortune. For a while, John's father refused to speak to him because of the marriage. Thomas Penn sponsored a trip for the younger Penn to Geneva to study and to get him away from his wife. Apparently regretting his marriage, Penn made no effort to contact Grace during this period. The Cox family sued Penn for support of Grace Penn in 1755, but after that time, no further reference to her appears in the Penn family records. How the marriage was dissolved is unknown; they had no children.[2]

Immigration to Pennsylvania[edit]

John Penn first traveled to Pennsylvania in 1752, sent by his uncle Thomas to the province as a political apprentice to Governor James Hamilton. Penn served on the governor's council, associating with important Penn family appointees such as Richard Peters and William Allen. In 1754, Penn attended the Albany Conference alongside other Pennsylvania delegates, including Peters, Benjamin Franklin, and Isaac Norris, but the younger man was there primarily as an observer.[3] The meeting was held by representatives of seven colonies to plan common defense against the French and Indians before the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War between Britain and France.

From his home in England, the chief proprietor Thomas Penn soon became alarmed at John's extravagant expenses. Peters reported John's close association with an Italian musician, whose rent Penn paid and at whose home Penn stayed until two or three in the morning. The "debauched" musician was, in turn, "constantly tagging after him".[4] Thomas Penn summoned his nephew John back to England in late 1755.[4]

Governorship[edit]

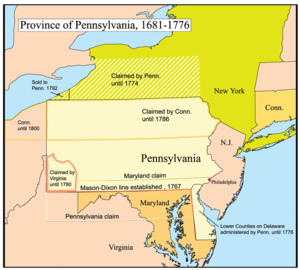

In 1763, Thomas Penn sent his nephew John Penn back to Pennsylvania to take over the governorship from Hamilton. The Penns were not displeased with Hamilton, but they believed John was prepared to assume leadership in the province for the family. He took the oath of office as governor—officially "lieutenant governor"—on 31 October 1763 and served until 1771 in his first tenure. The new governor faced many challenges: Pontiac's Rebellion, the Paxton Boys, border disputes with other colonies, controversy over the taxation of Penn family lands, and the efforts of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, led by Benjamin Franklin, to have the Penn proprietary government replaced with a royal government.

Marriage (2) and family[edit]

In 1766, Penn married Anne Allen, the daughter of William Allen and his wife, who were later Loyalists in Philadelphia. Penn reluctantly returned with his family to England in 1771 after his father's death, where he took over his father's position and affairs as one of the proprietors of Pennsylvania. His uncle Thomas Penn still held three-fourths of the proprietorship, but had a son born in 1760. John's brother, Richard Penn, Jr., was appointed governor of the province in his place.

Second appointment as governor[edit]

As Thomas Penn was displeased with Richard, Jr's performance, in 1773 he arranged for the re-appointment of John Penn as governor. Returning to the province with his family, Penn served until 1776. That year, the revolutionary government took control during the American Revolution.

Thomas Penn had died in 1775, and his son John Penn "of Stoke" inherited the chief proprietorship (and three-quarters of the total property). John Penn "of Stoke", born in 1760, was age 15 when his father died. He was assigned a guardian for the proprietorship until he came of age, but the Revolution disrupted his control of the holdings.

Revolution and after[edit]

The Penns were slow to perceive that the growing unrest which became the American Revolution would threaten their proprietary interests.[5] After the War of Independence began at Lexington and Concord, John Penn watched with apprehension as Pennsylvania colonists formed militia companies and prepared for war. Soon after the Declaration of Independence was adopted, "Patriots" (or "Whigs") in Pennsylvania created the 1776 Pennsylvania Constitution. It replaced Penn's government with a Supreme Executive Council. With no real power at his command, Penn remained aloof and carefully neutral, hoping the radicals would be defeated or at least reconciled with Great Britain.

The war soon began to go badly for the revolutionaries. In August 1777, as General William Howe began his campaign to capture Philadelphia, Patriot soldiers arrived at Penn's Lansdowne estate near Philadelphia. They demanded that he sign a parole stating that he would do nothing to harm the revolutionary cause. Penn refused and was taken to Philadelphia, where he was kept under house arrest. As Howe's army drew close, the Patriots threatened Penn with exile to another colony, and he signed the parole. With Howe near Philadelphia, Patriot leaders decided to exile Penn to an Allen family estate in New Jersey called "the Union", about 50 miles (80 km) from Philadelphia in present Union Township.[6] Anne Penn initially stayed in Philadelphia to look after family affairs while British forces occupied the city, but she later joined her husband in New Jersey.[7]

After the British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778, John and Anne Penn returned to the city in July of that year. The new government of Pennsylvania required that all residents take a loyalty oath to the Commonwealth or face confiscation of their property. With the consent of his family, John Penn took the oath.[8] While this protected Penn's private lands and manors, the Pennsylvania Assembly passed the Divestment Act of 1779. This confiscated about 24,000,000 acres (97,000 km2) of unsold lands held by the proprietorship, and abolished the practice of paying quitrents for new purchases. As compensation, John Penn and his cousin were paid £130,000. While it was a fraction of what the lands were worth, it was a surprisingly large sum, as in some areas Loyalist properties were taken without compensation.[9] Penn retired to Lansdowne and waited out the final years of the war, which ended in 1781.

For several years after the war, Penn and his cousin, John Penn "of Stoke", who had inherited three-fourths of the proprietorship and received that portion of the settlement, lobbied the Pennsylvania government for greater compensation for their confiscated property. John Penn "of Stoke" lived in Pennsylvania from 1783 to 1788. Failing there, they travelled to England in 1789 to seek compensation from Parliament. It awarded the Penn cousins a total of £4,000 per year in perpetuity.[10] (Penn "of Stoke" stayed in England for the rest of his life, serving as a Member of Parliament in the early 1800s.)

Returning to Pennsylvania, John Penn lived the rest of his life with his family quietly at Lansdowne. After his 1795 death, Penn was buried under the floor of Christ Church, Philadelphia, the only proprietor to be buried in Pennsylvania.[10] Some older accounts state that his remains were eventually taken back to England, but there are no records of this.[11]

John Penn was a grandson to William Penn the founder of Pennsylvania. He was the last proprietary governor of Pennsylvania serving first from 1763 through 1771 and then from 1773 until 1776 when the Revolutionary War began and most of his land and his positions were taken.

William Penn was granted a vast piece of land in the American colonies in1681 by Charles II of England in repayment of a debt owed his father, Sir Admiral William Penn. With the Crown granting a charter to Penn, he set the colony's governance up using a plan entitled "The Frame of 1682". It constituted a parliament consisting of two houses. The upper house, or the council, consisted of 72 members who were the first fifty purchasers of 5,000 acres or more in the colony and had the exclusive power to propose legislation. They were also authorized to nominate all officers in church and state and supervise financial and military affairs through committees. The lower house, or the assembly, consisted of smaller landowners. It had no power to initiate legislation, but could accept or reject the council’s legislative proposal only. The two-house parliament assisted the governor with his executive functions. By allowing landowners a say in the governing of the colony Penn was able to influence people to move there at the cost of quite a bit of power.

William Penn had two wives and even though he and his first wife had a son, William Penn Jr., Penn evidently favored the four sons he and his second wife had since he left them all his land in the Province of Pennsylvania. Of these four sons, Richard Penn was the father of John who along with his younger brother Richard (1736-1811) took turns as Governor.

When acting as Governor John was considered to be a fair man and thought to have done a good job.

During the early part of the Revolutionary War John and his wife Anne (Allen) remained loyal to the Crown albeit "neutral" but faced with losing everything in the colony they swore a loyalty oath to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1778.

After most of the Pennsylvania lands were stripped away from the Penn family, John and Richard, along with their cousin John (15 years old at the time but the holder of 75% of all the unsold chartered lands), won payment from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the amount of £130,000 "in remembrance of the enterprising spirit of the founder, and of the expectations and dependence of his descendants". Although the payment was a lot of money at the time it didn't come close to the actual value of what the Penn family had lost (estimated to be 24,000,000 acres). John and his brother Richard split 25% of the amount giving them each just £16,250. Later, after the war, the English government granted the Penn family an additional £4,000 per year in recognition of its lost sources of revenue. 12.5% of that, or £500 per year would go to John Penn.

Despite what happened during the Revolutionary War, John and his relatives still owned several thousand acres of privately held lands in Pennsylvania.

Of all the Penn family, John was the only one who made his home in Pennsylvania rather than returning to England. He would live out his years at Lansdowne Manor passing away in 1795.

Sources

- PERSONAL BIO WIKIPEDIA

Cadbury, Henry J. "John Penn". Dictionary of American Biography, vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 430. Treese, Lorett. The Storm Gathering: The Penn Family and the American Revolution. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-271-00858-X.

- Jenkins, Howard Malcolm. The Family of William Penn: Founder of Pennsylvania, Ancestry and Descendants

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Penn_(governor)

No known carriers of John's ancestors' DNA have taken a DNA test.

Have you taken a DNA test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

John is 22 degrees from Emeril Lagasse, 16 degrees from Nigella Lawson, 19 degrees from Maggie Beer, 37 degrees from Mary Hunnings, 30 degrees from Joop Braakhekke, 33 degrees from Michael Chow, 21 degrees from Ree Drummond, 26 degrees from Paul Hollywood, 23 degrees from Matty Matheson, 19 degrees from Martha Stewart, 31 degrees from Danny Trejo and 28 degrees from Molly Yeh on our single family tree. Login to find your connection.