| Preceded by 2nd Premier William Fox Preceded by 9th Premier Daniel Pollen Preceded by 8th Minister William Fitzherbert Preceded by 12th Minister Thomas Gillies Preceded by 13th Minister Harry Atkinson Preceded by 13th Minister Harry Atkinson Preceded by 7th Minister James Crowe Richmond Preceded by 2nd Minister Henry Sewell Preceded by 13th Minister George McLean |

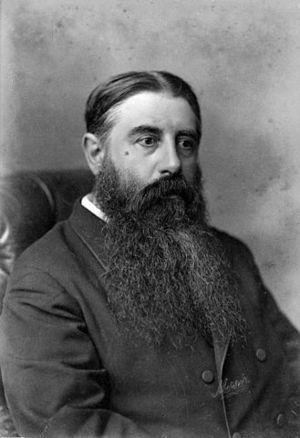

Sir Julius Vogel 8th Premier of New Zealand1873–1875 1876 11th Minister of Finance of New ZealandJun 28 1869 - Sep 10 1872 Oct 11 1872 - Jul 6 1875 Feb 15 1876 - Sep 1 1876 Aug 16 1884 - Aug 28 1884 Sep 3 1884 - Oct 8 1887 8th Minister of Customs of New Zealand28 Jun 1869 - 8 Jan 1871 30 Oct 1871 - 10 Sep 1872 3 Sep 1884 - 8 Oct 887 |

Succeeded by 9th Premier Daniel Pollen Succeeded by 10th Premier Harry Atkinson Succeeded by 12th Minister Thomas Gillies Succeeded by 13th Minister Harry Atkinson Succeeded by 13th Minister Harry Atkinson Succeeded by 13th Minister Harry Atkinson Succeeded by 2nd Minister Henry Sewell Succeeded by 9th Minister Oswald Curtis Succeeded by 18th Minister George Fisher |

Biography

Julius Vogel was born in the Dutch Jewish quarter of the East End of London. He was of Jewish descent [1] and taught at home by his parents, Albert Leopold and Pheobe Isaac. Julius parents separated when he was six years old [2] from which time onwards his maternal grandfather, Alexander Isaac, a West Indian merchant, cared for him. Julius studied at the University College School, made a voyage to South America under the auspices of his grandfather, and worked in a stockbroker's office. When the news of Australian gold fired his imagination, he took a course in metallurgy and chemistry at the Royal School of Mines in order to fit himself for a new life. He arrived alone in Victoria, Australia in 1852 at seventeen years of age.

Vogel opened a business, but after losses through speculation he went to the goldfields He started a drug store in the new town of Maryborough. An interest in journalism led to his becoming editor of the Inglewood Advertiser and the Talbot Leader. With journalism came an increasing interest in politics. Severe defeat in his candidature for the Avoca seat, combined with news of the Otago gold rush of 1861, drew his attention towards New Zealand.

He arrived in New Zealand1861 and, shortly after, his interest in journalism led to the establishment with a partner, W. H. Cutten, of the Otago Daily Times [2] which appeared on 15 November 1861. With Farjeon as manager, the paper was a brilliant success, but Vogel's continual advocacy of the separation of the North and South Islands, to relieve the latter of the burden of debt caused by the Maori Wars, led to his dismissal in 1868. In retaliation Vogel established The Sun as opposition, but shortly after discarded it to concentrate on national politics. His interest in journalism continued, however, for in 1870 he bought the Auckland newspaper Southern Cross.

Throughout the sixties Vogel's interest in journalism had been matched by his activity in local and national politics. After two vain attempts in early 1863 to enter the House of Representatives as a member for a Dunedin constituency, he had to be content with representing Waikouaiti in the Otago Provincial Council. Here he had greater opportunity to advocate publicly his views on separation, as well as to put forward his imaginative and often far-sighted ideas on subjects usually outside the scope of provincial politics. The period from 1863 to 1867 was a time of increasing political change and activity in Vogel's life. In September 1863 he was elected unopposed to Parliament for Dunedin Suburbs. Though his schemes were distrusted in the House of Representatives, he managed in 1866 to carry a resolution to reunite Otago and Southland. In the same year he was defeated in the contest for the Waikouaiti seat in the General Assembly. He resigned his seat in the Provincial Council and shortly afterwards contested and won the Taieri seat from a bitter opponent, A. J. Burns. Meanwhile he was again sent back to the House of Representatives for the goldfields. In February 1867 he further changed his seat to represent Dunedin in the Provincial Assembly, where he now became head of the Government. This position he held until he left Otago. A dispute between Macandrew the Superintendent of Otago, and the General Government over the administration of the goldfields gave Vogel his opportunity to continue his demand for provincial autonomy. Despite his vehemence he failed.

Meanwhile, in Parliament the absence of William Fox from politics gave Vogel the opportunity to become the leading light of the Opposition in its attacks on the native policy of Stafford. He also defended provincial rights against Stafford's centralism – a fact later used against himself when he, Vogel, began the fight to abolish the provinces. After the defeat of Stafford in June 1869 Vogel was appointed Colonial Treasurer, Postmaster-General, and Commissioner of Customs in Fox's Ministry. His concern with provincial matters now gradually lessened as he turned completely to national politics.

Fox was the titular head of the Ministry but Vogel soon became the real exponent of Government policy. He was now in a position to put into practice the large and imaginative schemes which provincial politics could not encompass, and which the national politicians had distrusted in earlier years. But by the end of the sixties the colony, in a state of economic stagnation, was ready to accept Vogel's dramatic Financial Statement of 28 June 1870 in which he proposed that development would be financed by £10 million, to be borrowed on overseas markets. The essence of the scheme he outlined in one sentence: “We recognize that the great wants of the Colony are – public works, in the shape of roads and railways; and immigration … the two are, or ought to be, inseparably united.…”. Provision for the repayment of the 5 ½ per cent interest charges was to be made from receipts above working expenses, from railway revenue, and from stamp duty. As security, and to ensure that the provinces would be able to meet repayments, Vogel intended that the land should bear a considerable portion of the financial burden.

Vogel stated three principles of Government policy regarding administration of public works and immigration. Both islands would share in the scheme; there would be no changes in political institutions; and although the need for colonisation was general, the Ministry realised that conditions throughout the colony varied widely. The scheme was intelligent and appropriate in its conception. Had its administration been careful and the safeguards heeded, it may have benefited the colony greatly. Vogel, however, was not the man to insist on maintaining the controls. His main object was to borrow the capital, regardless of the concessions he had to make to provincialism and local greed. Featherston and Bell were sent to England during the year to raise the money, but while they obtained a guarantee for £1 million, Vogel had authorised the spending of £4 million on the first stage of the policy. He himself left on a loan-raising visit to England and the United States at the end of 1870 and, after borrowing £1,200,000, granted railway and immigration contracts to John Brogden and Sons.

Vogel returned to the colony in 1871 and took his seat as member for Auckland City East constituency where his popularity was considerably higher than in Otago. Virtual leader of the Government and spokesman for its policy measures, Vogel was nevertheless not yet at the peak of his power. In 1872 sufficient caution still remained in the House for the prudent Stafford to defeat the Government in September and establish his own Ministry. Unfortunately for the cautious advocates, Stafford lasted only a month. Vogel returned to power with the support of the provincialist-minded politicians, and for the next three years his power was supreme. Although serving under two titular heads, he soon assumed the forms of power in addition to the substance. In April 1873 he became Prime Minister.

In the next two years, however, it became evident that the policy was running out of the control both of Vogel and of his Government, as insatiable provincialist members demanded capital in return for their votes. The principles which Vogel had enunciated were disregarded in the scramble and, gradually, he came to the conclusion that either the provinces or his scheme must be sacrificed. The pretext for action was the rejection of his New Zealand Forests Bill by the provincialists who objected to it as an encroachment by the Central Government on their land. But Vogel did not push through the unpopular Abolition Bill himself. He left in 1874 to raise another loan while H. A. Atkinson took over and passed the Act in 1875. In the following February Vogel returned to New Zealand as a K.C.M.G., but his long absence, charges of extravagance, the dislike of the provincialists, and the drop in export prices had reduced his popularity throughout the colony. In September 1876 he resigned the Premiership to become 'Agent-General in London'.

For almost eight years Vogel dropped out of New Zealand politics and in 1880 severed his connection with the colony altogether. After disputes with the Government over his connection with the New Zealand Agricultural Co., as well as his coming forward as candidate for a Cornish constituency while still representing New Zealand, he resigned the post of Agent-General.

In December 1882 Vogel visited New Zealand as the representative of the Electric Lighting Co.; he repeated the visit in 1883, this time on behalf of the Australian Electric Light, Power and Storage Co. On the second occasion he spent some time surveying the political scene and estimating his chances of re-entering colonial politics. New Zealand was by now dissatisfied with Atkinson's policy of cautious borrowing to finance steady economic development. Seeing this, Vogel put himself forward for the 1884 elections. His lack of popularity in 1876 was forgotten, and he became again the epitome of an almost forgotten “boom” prosperity. With such an electoral appeal he was returned to Parliament for the Christchurch North seat and found himself leader of the largest party, with 33 members of the 91 in the Assembly. With Stout as the nominal head of the Ministry he assumed power on 16 August 1884. The Ministry was defeated by a vote in the House on 28 August. In turn, Atkinson was defeated on 3 September and, again with Stout, Vogel held office until October 1887.

Vogel's final fling in politics was a disaster both for himself and for the colony. After a mildly successful first year in which he resumed borrowing at a rather higher rate than Atkinson had maintained, Vogel found that his policy of keeping depression at a distance by expenditure on public works was not staving off recession. In the face of worsening depression, and the continual defeat of Government on its financial policy, he was forced to fall back on retrenchment before Stout decided to end the humiliation, and the Ministry resigned in 1887. In the ensuing election Vogel was again returned for Christchurch North, but Stout was defeated and the Ministry lost its majority. Atkinson took office in October.

After his Ministry's resignation Vogel returned to London to devote himself to literature and, less successfully, to business. In 1889 he finally severed his political connections with the colony by resigning his seat. Illness and business failure prompted him to apply for a pension from the New Zealand Government. Eventually he was granted £300 a year in 1896, three years before his death. He died at Hillersdon, East Molesey, England, on 12 March 1899, and his widow later received £1,500 as a grant from the New Zealand Government. [2] (see notes below)

Sources

- ↑ Jews and Journalism, [1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Raewyn Dalziel. 'Vogel, Julius', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1990, updated September, 2022. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1v4/vogel-julius (accessed 18 June 2023)

See also:

- Wikidata: Item Q1363572, en:Wikipedia

- Julius Vogel

Notes

- All text from [2] licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand Licence unless otherwise stated. Commercial re-use may be allowed on request. All non-text content is subject to specific conditions. © Crown Copyright.

No known carriers of Julius's DNA have taken a DNA test.

Have you taken a DNA test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Julius is 20 degrees from Maria Mitchell, 30 degrees from Carl Sagan, 19 degrees from Tycho Brahe, 28 degrees from Nicholaus Copernicus, 25 degrees from Eise Eisinga, 16 degrees from Caroline Lucretia Herschel, 22 degrees from Thomas Maclear, 18 degrees from Simon Newcomb, 18 degrees from Isaac Newton, 20 degrees from Pierre Henri Puiseux, 18 degrees from Beatrice Tinsley and 22 degrees from Edith Woodward on our single family tree. Login to find your connection.