Chief

Benjamin

"Ben"

Marshall

Son of Thomas Marshall senior

and Hitskartay (Unknown) Marshall

[uncertain]

Brother of

Joseph Marshall, James Marshall, David Kowemarthlar Marshall, Henry Marshall, Matthew Marshall, William Marshall, Thomas Marshall junior, Lucy Marshall and Josey Marshall

[spouse(s) unknown]

[children unknown]

Profile last modified

| Created 2 Nov 2020

This page has been accessed 657 times.

The Birth Date is a rough estimate. See the text for details.

Biography

Origins

- Benjamin Marshall was born in or near Coweta in Lower Creek territory, Georgia.[1][2] He was the son of Thomas Marshall, an emigrant from county Tyrone, Ireland. An old contemporary, Thomas N. Woodward, remembered Benjamin as the son of "old man Marshall, an Englishman."[3] Alternatively, Benjamin was described as a "mixed-blood" Creek of Irish descent.[4][5] His mother might have been one of Mr Marshall's two wives, one of whom was known as Hits kar tay.[2] — Please see research notes: "Coweta place names in Georgia, Alabama, and the Indian Territory;" and "Children of Thomas Marshall."

Treaty of Indian Springs

- On 28th February 1825, Benjamin Marshall and his brother, Joseph, were two of fifty-two Creek representatives under Head Chief William McIntosh, who signed the Treaty of Indian Springs. By this treaty, the Creek representatives agreed to cede their lands lying within the State of Georgia and to the Removal of the Nation into the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi.[6] For various reasons, this treaty was superseded by the Treaty of Washington, which was executed on 24th January 1826. This treaty held that "the signatories of the Treaty of Indian Springs would have the same privileges as those who signed the new treaty. ... The Creeks legally retained possession of all their lands until January 1, 1827, after which they would retain a small portion on the Alabama-Georgia border."[7] On 30th April, Benjamin's friend, Chief William McIntosh, was executed at the hands of Creek dissidents,[8] a fate which Benjamin managed to escape.

- In accordance with the provision of that treaty, Chief Benjamin Marshall travelled to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River in late 1829,[9] as reported by The Georgia Enquirer, reprinted by The Arkansas Gazette:

- Benjamin Marshall, a Creek Chief, has just returned from Arkansas, and gives of the soil, climate, and abundance of game, so flattering an account, that all to whom he had made known the true situation and prospects of the country allotted to the Indians had signified their intention to emigrate; and it was Marshall’s opinion that half the Creeks would remove before next fall.—Georgia Enquirer.[10]

Friends of Chief William McIntosh

- On 5th December 1825, the following Marshall entries were recorded in a list of the friends and followers of the late General William McIntosh regarding the balance of Joel Baley, sundry goods to the amounts of:

- Col. Joseph Marshall for self and friends 561.87 1/2

- Capt. Benjamin Marshall 26.93 3/4

- Henry Marshall 32.75;

- William Marshall 8.00;

- James Marshall 35.50;

- Mathew Marshall 28.50;

- David Marshall 6.75.[11]

Predations on Creek property and a new treaty

- On 14th February 1831, an abstract of property taken from Creek Nation members by white people since 1825 included the following Marshall entries:

- Format: No., Indian name; Witness; horses / cows / hogs; By whom taken; Valuation; In what year taken

- No. 56, Mathew Marshall, Charly Marshall, 6 cows, Brodnax, $34, 1828

- No. 57, Dear?, Charly Marshall, 1 horse, 8 cows, Waley, $110, 1827

- No. 79, Henry Marshall, Charly Marshall, 14 cows, 9 hogs, citizens of Georgia, $100, 1827

- No. 80, T Marshall, David Marshall, 4 cows, 9 hogs, citizens of Georgia, $31, 1827

- No. 81, Mrs Marshall, Henry Marshall, [blank], citizens of Georgia, $40, 1927

- No. 82, James Marshall, Thos Marshall, 1 horse, 5 cows, 5 hogs, citizens of Georgia, $80., 1826 & 1827

- No. 83, Simmiar, David Marshall, 1 horse, citizens of Georgia, $80, 1828

- No. 113, Joseph Marshall, [—] & Esfa Micco?, 1 horse, 3[-] cows, 60? hogs, Thomas of Georgia, $310, 1826

- No. 118, Benj Marshall, [no witness], 10 cows, 20 hogs, Osburn of Georgia, [—], 1826[12]

- On 24th March 1832, the Creek Nation agreed a further treaty at the City of Washington, whereby the Creeks reaffirmed their agreement to cede their lands east of the Mississippi River and to be removed to the Indian Territory out west. The establishment of a trading post at Columbus on traditional Creek ground at Coweta Town in 1828, "in order to strengthen the western border of Georgia,"[13][14] appears to have given rise to the need for this further treaty. Pending their removal ("emigration"), twenty-nine sections, with patents, were granted to the Creek people on the west side of the Chattahoochee River in Russell County, Alabama. Additional annuities and other sums were promised for everything from the payment of debts, to compensate for improvements given up on their old lands east of the River, and so on. The treaty included a provision that any Creek people who wished to remain in the district could do so and receive U.S. patents in fee simple for their lands.[15]

Temporary settlement in Russell County, Alabama

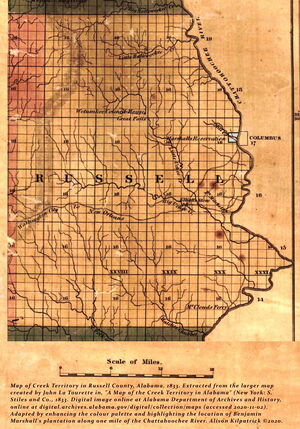

- Settling up his plantation on the east side of the river for the sum of $35,000,[16] Benjamin Marshall was granted a larger piece of land running one mile in a direct line along the west bank of the river and for a mile back.[15][17] This land enclosed Mill Creek and lay directly opposite the newly constituted town of Columbus. Of his tenure at this place, Haveman (2009) wrote, Benjamin Marshall constructed a mill adjacent to one of his fields on Mill Creek [in Russell County, Alabama], had numerous dwellings, and no doubt engaged in business with travelers using one of two roads that passed through his property,”[18] including a bridge over the Chattahoochee to Columbus.[19] — See the "Map of Creek Territory in Russell County, Alabama, 1833,"[20] included with this profile to see the location of Mr Marshall's plantation.

1833 census of the Creek Nation

- Accordingly, Benjamin Marshall was recorded in the census of the Creek Nation enumerated in eastern Alabama on 13th May 1833:[1][2]

- Census of the Principal Chiefs and Heads of Families of the Creek tribe of Indians, taken by virtue of the second article of the treaty concluded with that tribe at the city of Washington, March 24th, 1832.

- Names of the Principal Chiefs. …

- Co we ta Town. …

- – Joseph Marshall, 4 males, 2 females, 16 slaves, total: 22 (pg 335.) …

- Coweta Town – Kooch ka lecha. …

- – David Marshall, Ko we marth lar, 4 males, 2 females, 1 slave, total: 7

- – Benjamin Marshall, 2 males, 4 females, total: 6; US Interpreter

- Coweta, on Too silks too koo Hatch ee.

- – Henry Marshall, 1 male, 3 females, 2 slaves, total: 6

- – Matthew Marshall, 3 males, 2 females, total: 5

- – William Marshall, 1 male, 1 female, 1 slave, total: 3

- – Old Mrs Marshall, Hits Kartay or Hits kar tay, 2 females, 3 slaves, total: 5

- – James Marshall, 1 male, 1 female, 6 slaves, total: 8

- – Lucy Marshall, 1 male, 1 female, 1 slave, total: 3

- – Josey Marshall, 1 male, 1 female, total: 2

- – Thomas Marshall, 1 male, 4 females, 2 slaves, total: 7

- Thlobhtlocco Town 2

- – John Marshall, 1 male, 1 female, 5 slaves, total: 7[2] (possibly the son of Thomas Marshall's son, Joseph.)

- Footnote (in original text): Benjamin Marshall[,] the United States interpreter, for the Creek nation of Indians, having already by the late treaty had a special reservation of land assigned him, and having presented himself before me, and asserted a right to be enrolled as the head of a family, in order to be put in possession of the quantum of land reserved to heads of families respectively, I deemed it my duty to note his case, and submit the same to the determination of the department. T. J. A.[1][2]

Removal to the western Indian Territory

- Nearly five months later, in November 1833, during the early stages of the Removal, the Creek Nation was enumerated in the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. A total of 2,459 people were counted, of whom 30 were white, 2 Cherokee, 13 free black people, and 498 enslaved black people. The remaining 1,918 people comprised Creek Indians, of whom 236 were in Coweta Town. John Campbell, agent for the Western Creek Agency, appended the following note:

- This part of the Creek nation numbered near three thousand, three years ago, and they are on the decline ever since their arrival here; from the prevailing diseases of the country; there are not more than a fourth of the Indian Children that were born in this country that is now living; there is a great want of medical assistance wanting here; for the first two or three years after the emigrants reached this country; so that they could be rendered all the necessary medical aid, until their Constitutions, would get formed and a---tated [acclimated?] to the climate.[21]

- Sanford & Company, a contractor for the removal of the Creeks from Alabama, engaged Benjamin Marshall to facilitate enrolment. Benjamin agreed, if only because he was most anxious to "get his negroes removed" before he and his family left at a later date. On the first leg of their journey, a party of 511 souls, including thirty-five of Benjamin's slaves, made the first leg of their journey, arriving at Wetumpka, Alabama.[22] Benjamin was also anxious to move his kith and kin because they "were being furnished with whiskey and all they possessed was carried to grog shops."[23] Weighing heavily on all of the Nation were increasingly violent acts perpetrated by an aggrieved white population, in particular, against those Creek Indians who had elected under the Treaty of 24th March 1832 to stay in their homeland.[24] — Note: The diary of the journey of this particular journey has been reproduced in Gaston's "The Journal of a Party of Emigrating Creek Indians, 1835-36." For sixty-one days, this party travelled a distance of 750 miles from Wetumpka to Fort Gibson, by foot and by steamboat.[25]

- For his part, Benjamin's departure was delayed by having to attend to legal matters involving his late brother's Joseph's estate.[22] In the fall of 1836, Benjamin and his party,—comprised of forty-five Creek people, most of whom were his relatives (his immediate family counted eight in number), and twenty-eight slaves,—made the journey out west without the aid of an emigration company.[22][23] The party arrived at Fort Gibson on 14th January 1837.[26]

Plantation at Marshalltown

- Benjamin Marshall settled his family at the fork of the Arkansas and Verdigris Rivers in the Coweta District of the Creek Nation.[23][27] In an interview conducted in 1937, his grandson, Richard Adkins, recalled that:

- In the following years he accumulated three large farms by hard work and using good business judgment. Mr. Marshall, farming on a large scale, raised wheat, oats, rice, corn and cotton with the aid of one hundred or more slaves that he owned. He bought hides, corn, oats, wheat, wood and pecans from the Indians on the Verdigris River, where he had a warehouse eight miles north of Muskogee.

- The small steamers would come by way of the Arkansas and Verdigris Rivers to Mr. Marshall’s warehouse and he would ship his produce to Fort Smith, Arkansas, selling the produce at a nice profit.[28]

- Benjamin also bought, sold, and enslaved black people up till the Civil War. He was said to have employed about one hundred slaves on his plantation.[27][28]

- In time, Benjamin Marshall's district became known as Marshalltown.[27]

1843 census and Creek Nation administration

- By the end of 1843, the number of Creek people amounted to 14,440. The number of black people tallied to 50 freed men and 1,077 enslaved. General Roly McIntosh, Head Chief, estimated that two thousand of the Creek people had dispersed into the Cherokee Nation (700), Chickasaw Nation (500), the Old Nation (300), into the Mississippi swamps (150), into Texas (250), and into Mexico and associated hunting grounds (100).[29] Amongst the Creek people, there were bands speaking different languages, e.g., the Uchees, Hitchitys, Natches, Piankeshaws, Cooshatties, &c.[30]

- In 1847, Mr Marshall was selected to fill the vacant post of Second Chief of the Lower Towns in the Creek territory. He was deemed to have been "favorably inclined to religion and education, and much good may be anticipated to arise from his appointment."[5]

- On 7th August 1856, the Creek Nation agreed to cede a tract of land to the Seminole Nation. The signatories included George Manypenny [commissioner on the part of the United States], Tuck-a-batchee-micco, Echo-Harjo, Chilly McIntosh, Benjamin Marshall, George W. Stidham, and Daniel N. McIntosh were the Creek commissioners while the Seminoles were represented by John Jumper, Tuste-nue-o-chee, Pars-co-fer, and James Factor, commissioners on the part of the Seminoles.[15][31]

1857-59 census and 1860 slave schedule

- Some twenty years after the Removal of the Creek people from their homelands east of the Mississippi, a census conducted between 1857-59 recorded Benjamin Marshall's household in the western Indian Territory as follows:

- Benjamin Marshall, total in family: 7, amount due each $16.65, amount receipted for $116.55, signature: Benjamin Marshall

- Fanny Marshall (in the typescript copy), but Betsy per the digital image

- Martha Marshall

- George Marshall

- Benjamin Marshall

- Elmira Adkins

- Rosell[a] Adkins

- census place: Coweta Town (household no 90). Lower Creek Towns[32]

- The 1860 U.S. census slave schedules included the number of enslaved inhabitants in the Creek Nation. As of 5th November 1860, Benjamin kept seventy-five black people,[33] of whom:

- 65 were under the age of forty years, of whom 47 were under the age of thirty years, and the eldest was an 86-year-old black man;

- 41 were female, and 31 were male; and

- 54 were black, and 21 classified as “mulatto.”[34]

- The largest group were little girls under the age of ten years (15), older girls (13), and young women (7). All but one of the “mulatto” group were under the age of twenty, thirteen of whom were young children.[34]

Claim filed under Article 6 in 1859

- On 15th February 1859, claims were filed under Article 6 of the Treaty of 7th August 1856. The list of Marshall individuals who were entitled to participate in the fund of $70,000 included the following, all in Coweta Town:

- Jno. Marshall $600

- Joseph Marshall $1000 †

- Polly Marshall $1000 ‡

- Benjamin Marshall $1000

- Henry Marshall $400

- Mathew Marshall $900

- James Marshall $400

- Thomas Marshall senr. $1000

- Nicholas Marshall $55 ‡

- Betsey Marshall $245 [35]

- Notes:

- – Article 6 provided, in part, for "$70,000 for the adjustment and final settlement of such other claims of individual Creek Indians, as may be found to be equitable and just by the general council of the nation."[15] This part of Article 6 appears to apply to the Creek Indians who had received reservations in the land on the western side of the Chattahoochee River in 1832, prior to their Removal to the West.

- – Those names marked ‡ appear to be descendants, whose names were not recorded in the 1833 census in eastern Alabama.

- – † Which Joseph Marshall was meant is not clear, as Chief Joseph Marshall died in the Creek reserve land (Alabama), c.1833,[3] and the two Joseph Marshalls recorded in the 1857-59 census of the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) were not heads of household.[36]

The Civil War and Death at Old Stonewall

- Richard Adkins related the last chapter of his grandfather's story, viz.—

- After the Civil War started, Mr. Marshall, his wife, two daughters, and his grandson Richard Adkins, started south with six or seven wagons and thirty slaves. The other slaves that Mr. Marshall owned escaped and went North.

- As treasurer of the Creek Nation, Mr. Marshall was in possession of a large amount of gold, silver, and paper money that belonged to the tribe as well as his own fortune. Burdened with the responsibility of guarding the money Mr. Marshall would bury the money which he had placed in coffee pots and gallon cans with the help of his slaves every night when he camped for the night. With Mr. Marshall and his family moving south after the start of the Civil War were the Lewis’ and the McIntosh’s; Roley, John and Ennis McIntosh who later joined the Confederate Army.

- Mr. Marshall first stopped near the mouth of Deep Fork Creek, south of Okmulgee, where they made one crop, but as the fighting between the Southern and Northern armies was getting closer to Deep Fork, Mr. Marshall moved on again to Big Blue Creek and finally settled near Old Stonewall. [...]

- Mr. Richard Adkins’ mother, Millie Adkins, and his grandfather, Ben Marshall, died during the third and fourth years of the Civil War. They were buried in John Petslinn graveyard, fifteen miles south of Old Stonewall.[28]

- Thus, Benjamin Marshall died in 1864, and was buried at the old location for the village of Stonewall, southeast of Ada in Pontotoc County.[37]

Postscripts

- Many were the men who attempted over the succeeding years to find buried treasure in this locale, without success, as old man Marshall took the secret of its burying place to his own grave.[38] — Note: See the digital image of the article published to this effect in the 5th January 1919 edition of The Daily Oklahoman, filed under the "Images" tab of this profile.

- Benjamin Marshall's estate was tied up in the courts as late as 1875. His son, George W. Marshall, was the administrator "according to the laws and customs of the Creek nation of Indians." In 1860, Ben. Marshall, a native and citizen of the Creek nation, had recovered judgement in action against William B. Nowland in Crawford Circuit Court, in the amount of $1692.23. However, pending the suit, he died in the Indian nation, intestate. A man named Whitesides was appointed administrator of the estate, in whose favour judgement was found on 10 November 1868 for $2757. George and six others, all children of Benjamin Marshall, claimed to be the sole heirs at law. They brought a suit to the Supreme Court of Arkansas against a series of people, including Whitesides aforementioned, and Messrs Thomason and Humphries, attorneys of the estate.[39]

- A man of complex qualities, Benjamin Marshall was described as "a man of unblemished character and one of the most farseeing statesmen the Creek people ever had, and one of the chief councillors of the nation." He served as national treasurer for forty years, was entrusted as one of the Chiefs of the Creek nation to treat with the U.S. government, and served as national interpreter.[5][23] Yet this was also a man who, like some of his Creek peers, enslaved black people and acquired great wealth thereby. Finally, and notwithstanding his reasons, notably the welfare of his Creek family and neighbours in the face of a hostile takeover of their homeland, Chief Marshall's rôle in facilitating the Removal of the Creek Nation remains controversial—memorialized as one of the several infamous Trails of Tears which led the Creek Nation out of the southeastern United States, 750 miles away into the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi.

Research notes

- Estimated date of birth:—His brother Joseph having been active in Creek Nation affairs at an earlier date, it seems reasonable to assume that Benjamin Marshall was the younger of the two. However, Benjamin acquiring the honour of the title of Chief, suggests also that siblings other than Joseph were younger. In any event, without other sources, the year, 1790, is an estimate, only. ~Kilpatrick-1128 (2020-11-03)

- Coweta place names in Georgia, Alabama, and the Indian Territory:—Coweta was a tribal town of the Lower Creek Indians. Until c.1828, Coweta was sited on the eastern side of the Chattahoochee River, in Georgia, about three miles below the falls (at modern Waveshaper Island), on a flat extending back one mile.[40] After the Treaty of Indian Springs (1825), the Lower Creeks of Coweta removed first to the western bank of the Chattahoochee River in Alabama. One of the new settlements in what is now Russell County, just south of (modern) Phenix City, was given the name, Coweta Town.[1][2][41] When the Lower Creek people were removed from Alabama during the 1830s to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River, one of the places in that Territory acquired the name, Coweta.[42]

- Children of Thomas Marshall, sen.:—One source identifies Thomas as having a Creek nation wife as early as 1784.[43] By 1797, he had two Creek wives.[44] While an old, contemporary Coweta resident, Thomas S. Woodward, identified Thomas Marshall's three sons as Joseph, James, and Benjamin,[3] the 1832 census lists six other individuals who might also have been Thomas's children, perhaps by his second wife or otherwise; or some might have been Thomas's grandchildren, just old enough in 1832 to have their own households. In any event, information has yet to be found about the number of Thomas's children and which wife gave birth to each. — In order to record profiles for the Marshalls enumerated in the 1832 census, each will be assigned as children of Thomas and Hitsarkay pending the discovery of records which might shed light on the specifics of the family constellation. ~Kilpatrick-1128 (2020-10-27)

- This profile is a collaborative work-in-progress. Can you contribute any information or sources?

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 United States of America. Correspondence on the Subject of the Emigration of Indians, between the 30th November, 1831, and 27th December, 1833. Vol. IV. “Census of the Principal Chiefs and Heads of Families of the Creek tribe of Indians, taken by virtue of the second article of the treaty concluded with that tribe at the city of Washington, March 24th, 1832.” Washington: Duff Green, 1835.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.6: Records Relating to Indian Removal. “By a treaty of March 24, 1832, the Creek Indians ceded to the United States all of their land east of the Mississippi River; &c.; certified 13th May 1833.” Microfilm ref. T275, roll 1. Transcripts posted to Creek Indian Records, “1832 Creek Nation (Alabama) Census;” (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Woodward, Thomas S. Woodward’s Reminiscences of the Creek, or Muscogee Indians, contained in Letter to Friends in Georgia and Alabama. Montgomery, Alabama: Barrett & Wimbish, 1859.

- ↑ Schoolcraft, Henry R. Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Conditions, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Part 1. Ch. 9, “Some Information Respecting the Creeks, or Muscogees.” Extract: “8. The present rulers of the nation consist of a first and second chief, who, in connection with the town chiefs, administer the affairs of the nation in general council. The present principal chief, General Roly McIntosh, is of Scotch descent. The second chief, Benjamin Marshall, is of Irish descent: both the friends of the white man.” (pg 267.) Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, 1851.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Foreman, Carolyn Thomas. “Marshalltown, Creek Nation.” (pp 52–57.) Citing: Grant Foreman, Indian Removal (Norman, 1932), pg. 142; Office Indian Affairs, Creek Emigration, muster roll, October, 1835†. The Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. XXXII, No. 1 (Spring 1954). Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society, 1954; printed by Co-Operative Publishing Co., Guthrie, Ohio. Record by National Archives (USA), “Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs [BIA,” Record Group 75. Microfilm copies of records listed online, www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/075.html (accessed 2020-10-27).

- ↑ State of Georgia (USA). Governor’s Message. General Assembly of the State of Georgia at the opening of the Extra Session. May 23, 1825. Milledgeville: Camak[?] & Ragland, printers, 1825.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Treaty of Washington (accessed 2020-11-01).

- ↑ Wikipedia. William McIntosh (accessed 2020-11-01),

- ↑ The Savannah Georgian, 17 November 1829 (pg. 4). "Indian Affairs." Digital image online at newspapers.com (accessed 2020-10-28).

- ↑ The Arkansas Gazette, 6 January 1830 (pg. 3). Citing Benjamin Marshall, a Creek Chief, having returned to Georgia from Arkansas. Reprinted from the Georgia Enquirer. Digital image online at newspapers.com (transcript by Alison Kilpatrick, 2020-10-28).

- ↑ National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.4: General Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. “The friends and followers of Genl. William McIntosh. Georgia, Indian Springs. The friends & followers of the late Genl. William McIntosh of the Creek Nation, bal. of Joel Baley. Sundry goods to the amt. of - annexed to thus Several Names (Viz).” Marshall entries include: Col. Joseph Marshall for self and friends 561.87 1/2; Capt. Benjamin Marshall 26.93 3/4; Henry Marshall 32.75; William Marshall 8.00; James Marshall 35.50; Mathew Marshall 28.50; David Marshall 6.75. This 5th December 1825.” Microfilm ref. M234, reel 220, 338-39. Transcript posted to Creek Indian Records (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.4: General Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Microfilm ref. 234, roll 222, frames 418-23. Extracts entitled, “An Abstract of Property Taken by White Citizens of the United States from the Creek Indians since the year 1825.” Posted to Creek Indian Records, “Abstract of Indian Claims against citizens of Georgia & other states to be laid before the Govr't, Feb 14, 1831;” (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ Columbus, Georgia. History of Columbus, Georgia. Online at www.columbusga.gov/history/ (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ Wikipedia. Columbus, Georgia: History (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Ricky, Donald B., ed., and Nancy K Capace. Encyclopedia of Michigan Indians. Vol. 2. Treaties. Tribes, Nations, and People of the Northern Woodlands. St. Clair Shores, Michigan: Somerset Publishers, Inc., 1998.

- ↑ Haveman, Christopher D. The Removal of the Creek Indians from the Southeast, 1825–1838. A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Citing: John H Brodnax to Lewis Cass, 28 May 1933. National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75, Letters Received by the OIA, Creek Agency Reserves. Microfilm ref. M234, reel 241, 210–211. Auburn, Alabama: Auburn University, 10 August 2009. Online at etd.auburn.edu (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ Haveman wrote: "In fact, agents discovered Benjamin Marshall moving his sister onto a better piece of land before the reserve was assigned." Source: Haveman, Christopher D. The Removal of the Creek Indians from the Southeast, 1825–1838. A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Citing: National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75. Leonard Tarrant to Elbert Herring, 15 May 1833; Letters Received by the OIA, Creek Agency Reserves. Microfilm ref. M234, reel 241, 465–476. Auburn, Alabama: Auburn University, 10 August 2009. Online at etd.auburn.edu (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ Haveman, Christopher D. The Removal of the Creek Indians from the Southeast, 1825–1838. A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Auburn, Alabama: Auburn University, 10 August 2009. Online at etd.auburn.edu (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ U.S. Land Office. Tallapoosa Land District, Plat Book. Reel 30, 161. Held by Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery Alabama. Cited in, Haveman, Christopher D. The Removal of the Creek Indians from the Southeast, 1825–1838. A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Auburn, Alabama: Auburn University, 10 August 2009. Online at etd.auburn.edu (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ La Tourrette John. A Map of the Creek Territory in Alabama, from the United States Surveys. Shewing each Section & Fractional Section. Entered according to the Act of Congress in the year 1833 by John La Tourrette in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the Southern District of Alabama. Florence, Alabama: Surveyor’s Office, 13 April 1833. Digital image hosted online by Alabama Department of State Archives and History, digital.archives.alabama.gov (accessed 2020-10-29). Adapted by enhancing the colour palette and highlighting the location of Benjamin Marshall’s plantation lying one mile alongside the Chattahoochee River and one mile back from the river. Alison Kilpatrick ©2020.

- ↑ National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.4: General Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. “A Roll of the Census of the Creek Nation West of the Mississippi River the 30th September 1833.” Microfilm ref. M234, roll 236, frame 371. Transcript posted to Creek Indian Records; (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Haveman, Christopher D. Rivers of Sand: Creek Indian Emigration Relocation, and Ethnic Cleansing in the American South. Nebraska: Lincoln and London UNP, 2016.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Foreman, Carolyn Thomas. “Marshalltown, Creek Nation.” (pp 52–57.) Citing: Grant Foreman, Indian Removal (Norman, 1932), pg. 142; Office Indian Affairs, Creek Emigration, muster roll, October, 1835†. The Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. XXXII, No. 1 (Spring 1954). Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society, 1954; printed by Co-Operative Publishing Co., Guthrie, Ohio. Record by National Archives (USA), “Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs [BIA,” Record Group 75. Microfilm copies of records listed online (accessed 2020-10-27).

- ↑ National Park Service. "The Creek Indian War of 1836." Online at www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture (accessed 2020-11-03).

- ↑ Litton, Gaston. “The Journal of a Party of Emigrating Creek Indians, 1835-36.” (pp 225–242.) The Journal of Southern History. Vol. 7, No. 2 (May 1941). Published by Southern Historical Association.

- ↑ National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.4: General Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Microfilm ref. 234, rolls 237–240. Select transcripts hosted online, “Creek Emigrants to the Western Creek Nation, Muster Rolls and Letters, 1826-52+;” transcript posted to Creek Indian Records (accessed 2020-10-29).

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Baird, W. David, ed. A Creek Warrior for the Confederacy: The Autobiography of Chief G.W. Grayson. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Fife, Dawes. Interview with Richard Adkins of Sapulpa, Oklahoma. Citing Mr Adkins’ family history including Mr Ben Marshall, his grandfather, and Martha (MIllie) Adkins née Marshall, his mother. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma. Digital images online at digital.libraries.ou.edu/cdm/ref/collection/indianpp/id/2994 (transcript by Alison Kilpatrick, 2020-10-27).

- ↑ National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.15.12: Records of the Southern Superintendency. “Statement of General result of the Creek Census;” counted circa December, 1843. Microfilm ref. M640, roll 4, frame 1175. Transcripts posted to Creek Indian Records (accessed 2020-10-30).

- ↑ National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.4: General Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. “Letter to T. Hartley Crawford, Esq., Commissioner, Indian Affairs, from J.L. Dawson, Creek Agent, 19th September 1842. Microfilm ref. M234, roll 923, frames 544-45. Transcript posted to Creek Indian Records (accessed 2020-10-30).

- ↑ Foreman, Carolyn Thomas. “John Jumper.” The Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. XXIX, No. 1 (Spring, 1951). Published by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

- ↑ Oklahoma and Indian Territory. Census, 1857–1859. Household of Benjamin Marshall in Coweta Town. Original record: The National Archives at Fort Worth, Texas, USA; Record Group Number: 75; Record Group Title: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1793-1999; NARA Series Number: 7RA-23; NARA Series Title: Creek Rolls, 1857-1859; pg. 365 of original, pg. 269 of typescript copy. Digital image online at ancestry.ca (extract by Alison Kilpatrick, 2020-10-27).

- ↑ U.S. 1860 Census. Slave Schedule. Benjamin Marshall of the Creek Nation, in the country west of the State of Arkansas. Original record: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. Archival ref. series no. M653, record group: Records of the Bureau of the Census (no. 29). Digital images online at ancestry.ca (accessed 2020-10-27).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Kilpatrick, Alison. Demographic analysis of the people enslaved by Benjamin Marshall of the Creek nation, in the country west of the state of Arkansas, 1860 (prepared 27 October 2020, © Alison Kilpatrick). Data from the U.S. 1860 Census “Slave Schedule.” Original record held by The National Archives (Washington, D.C.), Record Group No. 2.

- ↑ National Archives (USA). Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Record group: RG-75.4: General Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Microfilm ref. M234, roll 230, frames 398ff. Transcript posted to Creek Indian Records, “This is a list of claims connected with the payment of funds stipulated in the 6th Article of the Treaty of 7th August 1856;” (accessed 2020-10-30).

- ↑ Oklahoma and Indian Territory. Census, 1857–1859. Original record: The National Archives at Fort Worth, Texas, USA; Record Group Number: 75; Record Group Title: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1793-1999; NARA Series Number: 7RA-23; NARA Series Title: Creek Rolls, 1857-1859. Digital images and typescript copies online at ancestry.ca (extract by Alison Kilpatrick, 2020-10-27).

- ↑ Find-a-Grave Memorial No. 199309754. Extract: Chief Benjamin “Ben” Marshall, born in 1800 at McIntosh, Liberty County,‡ Georgia; died in 1864 in Pontotoc County, Oklahoma, USA; buried in Frisco Cemetery, Frisco, Pontotoc County, Oklahoma. Memorial created by “wayne,” 21 May 2019 (accessed 2020-10-27). Notes: ‡ Unlikely, but rather, and almost certainly, in Coweta Town.

- ↑ The Daily Oklahoman, 5 January 1919 (pg 37). “Tales of Buried Gold Left by Wealthy Territorial Aristocrat Cause of Many Midnight Rides.” Citing the gold, silver, and cash buried by Benjamin Marshall at or near Stonewall, Oklahoma. Digital image online at newspapers.com (accessed 2020-10-27).

- ↑ Moore, John M.. Reports of Cases at Law and in Equity argued and determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Arkansas, containing Cases Decided at the May & November Terms, 1875. Vol. XXX. “DuVal et al vs. Marshall.” (pp 230-49.) Little Rock, Arkansas: Adams & Blocher, 1877.

- ↑ Collections of the Georgia Historical Society. Vol. III, Part I. "The towns on Chat-to-ho-che, generally called the Lower Creeks. 1. Cow-e-tugh." (pp. 52ff.) Savannah: Printed for the Society, 1848.)

- ↑ Waymarking.com. "Coweta Town (KVWETV) – Phenix City, Alabama." Online at www.waymarking.com (accessed 2020-11-04).

- ↑ Oklahoma and Indian Territory. Census, 1857–1859. Household of Benjamin Marshall in Coweta Town. Original record: The National Archives at Fort Worth, Texas, USA; Record Group Number: 75; Record Group Title: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1793-1999; NARA Series Number: 7RA-23; NARA Series Title: Creek Rolls, 1857-1859; pg. 365 of original, pg. 269 of typescript copy. Digital image online at ancestry.ca (extract by Alison Kilpatrick, 2020-10-27).

- ↑ Snyder, Christina. Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America. Extract: “Thomas Marshall, whose wife was Creek, demanded justice, …”, i.e., on the occasion of the murder of Thomas’ brother, William. (pg. 170.) Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- ↑ Hawkins, Benjamin. Letters of Benjamin Hawkins 1796–1806. Collections of the Georgia Historical Society. Vol. IX. Savannah, Georgia: The Morning News, 1916.

Links

- Wikipedia. Muscogee Creek

- FamilySearch Int'l. Creek Indians

- New Georgia Encyclopedia. Creek Indians

- Wikipedia. Trail of Tears

- Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Slavery in the United States

Is Benjamin your ancestor? Please don't go away!

Login to collaborate or comment, or

Login to collaborate or comment, or

contact

contact

the profile manager, or

the profile manager, or

ask our community of genealogists a question.

ask our community of genealogists a question.

Sponsored Search by Ancestry.com

DNA

No known carriers of Benjamin's ancestors' DNA have taken a DNA test.

No known carriers of Benjamin's ancestors' DNA have taken a DNA test.

Have you taken a DNA test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Images: 6

Comments

Leave a message for others who see this profile.

There are no comments yet.

Login to post a comment.

Featured Female Poet connections: Benjamin is 16 degrees from Anne Bradstreet, 23 degrees from Ruth Niland, 30 degrees from Karin Boye, 29 degrees from 照 松平, 16 degrees from Anne Barnard, 39 degrees from Lola Rodríguez de Tió, 27 degrees from Christina Rossetti, 15 degrees from Emily Dickinson, 34 degrees from Nikki Giovanni, 22 degrees from Isabella Crawford, 24 degrees from Mary Gilmore and 14 degrees from Elizabeth MacDonald on our single family tree. Login to find your connection.

M > Marshall > Benjamin Marshall

Categories: Muscogee Creek Trail of Tears | Estimated Birth Date | Creek