Contents |

Biography

|

| London in 1758 |

Richard Chamberlayne Esq was a Citizen of London, silk mercer to the Royal Household of King George I, [1]and became a wealthy landowner. He was High Sheriff of Essex in 1722 and Justice of the Peace for Islington, Middlesex.

In many ways, the history of the Chamberlayne family from the end of the 1600s reflects in microcosm the way that the English Middle Class developed. [2]From an origin in minor Anglo-Norman nobility with the inevitable marriage of cousins, affected like every other family by the Civil War and social change, throughout the centuries the English side of the family gradually moved from being courtiers and administrators into merchant trade and the law. After the Great Plague of 1665 and the Fire of London, London was rebuilt and became again the place of opportunity. Although Stoney Thorpe near Long Itchington in Warwickshire continued to be the Chamberlaynes' country seat, the establishment of status and fortune was to be found in London. Younger sons profited from the demise of their older brothers, and marriages were made into families which had developed along similar lines, such as the Brocketts, the Caves, and those with Huguenot backgrounds, like the Fauquiers.

- The end of the 17th Century was difficult. The weather, which had also been atrocious in the 1640s, entered a bleak spell in the 1690s with a series of pitiably poor, starvation harvests. Revenues and rents from land began to be depressed. The growth in population slowed. On top the that, the new government that had come in with the Dutch William III was now militarising fast. Between 1689 and 1714, the Royal Navy became the biggest in Europe. In 1692, a land tax was imposed at 4 shillings in the pound, a 20 per cent tax on gentry incomes. A government which had looked as if it would be the embodiment of landholding England became instead the government of a combination of the Whig aristocrats, the commercial interests of the City of London and its growing Atlantic empire.

- In the century to come, which would belong to the merchants and the great Whig oligarchs, the nature of the gentry began to divide into an old Tory world view and a new Whig one. If there is a hinge in gentry history, this is it. [3]

|

Birth, Parentage and Childhood

Two years before the death of Charles II, Richard Chamberlayne was born in February 1683, and baptised on 22 February, [5][6]the son of Edward Chamberlayne [7] and Jane, his wife. [8]

Born in Warwickshire, at the manor of Princethorpe, on the Fosse Way, halfway between the towns of Rugby and Leamington Spa, Richard entered Rugby School when he was eight years old, in 1691. [9]

His infant sister Jane died when he was nine, and two years later his father died. He was fourteen when his older brother Edward died, and 24, 25 and 26 when his sisters Frances and Elizabeth and then his brother John died, leaving him the inheritor of Princethorpe.

He would have had to care for his mother and siblings and manage his deceased father’s estate for some time.

Princethorpe[10] was originally in the parish of Wolston but was made, for convenience, a separate parish with Stretton by an Act of Parliament in the reign of William III.[11] The Parish was to be known as the Parish of All Saints with the vicar, Francis Hunt,[8] a cousin of the Chamberlaynes, residing in Stretton.

Life and Career

On 10th September 1700, for the statutory duration of seven years, Richard apprenticed himself to John Rudyard, Citizen and Skinner of London, his 5th cousin twice removed, a man contracted to build the second Eddystone Lighthouse, and whose family owned a well-respected silk trading business on Ludgate Hill, London.[12] [13] Many of Richard's family members had made their fortunes in various merchant trades in London; being attached to an influential Guild member would have been an advantage.

Now a mercer (a dealer in textile fabrics, especially silks, velvets, and other fine materials), according to the Archivist of the Mercers' Company*, Richard never became a member of the guild. By this time, the Mercers had lost much of the influence and power they had had between the Middle Ages and 16th Century, and

- the Company began to fall into debt so that the beginning of the 18th century they were insolvent. They had loaned money out to help public services in need but many of these debts had not been honoured, now all those who the Company sought to assist were in distress[14]so to be an independent retailer may have been preferable. Through his business contacts in the City of London, and probably through knowing Thomas Dummer, who was also Deputy Master of the Great Wardrobe,[15][16] Richard made valuable business contacts.

In the Spectator of 27 October 1714, barely four weeks after the coronation of King George I, Richard advertised the fact that he had moved his business from The Great Wheat-Sheaf to the King's Arms on Ludgate Hill, a thriving centre of Mercer activity, and selleth all Sorts of Silks, Silver and Gold Stuffs, &¢.

|

| Advertisement for Richard Chamberlayne[17] |

|

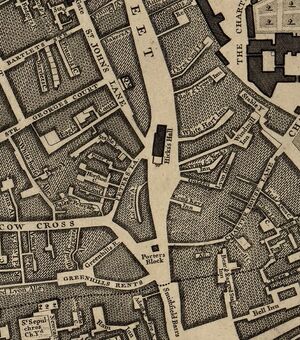

| Richard Chamberlayne's London; King's Arms on Ludgate Hill and St Bride's Church, Fleet Street, from John Rocque's Map of London, 1746.[18] |

In 1714, his name appears in the Index of Royal Household Staff.[19][20]Guild membership was unnecessary - royal patronage was advertisement enough. On 28 March 1715, he was commissioned to supply the crimson silk for 18 stools and matching hangings for the state bed of Georg August, Prince of Wales, and his bride, Princess Caroline, in Hampton Court Palace.[21]

|

| State Bed |

On 31 January 1716, the Prince of Wales approved and signed an account for amongst other things, soft furnishings for the Council Chamber and royal bedchambers at St James' Palace, commissioned from Richard Chamberlayne and Company, Mercers. [22]

Richard Chamberlayne, Mercer[19]

| Name of Company | Time period |

|---|---|

| Richard Chamberlayne & Company | 1 Aug 1714 – Michaelmas 1715 |

| Richard Chamberlayne & Partners | Michaelmas 1715 – 1716 |

| Richard Chamberlayne & Partner | Michaelmas 1716 – 1717 |

| Richard Chamberlayne & Partner, Mercer | Michaelmas 1717 – 1718 |

| Richard Chamberlayne & Partner, Mercer | Michaelmas 1718 – 1719 |

| Richard Chamberlayne alone, Mercer | Michaelmas 1719 – 1720 |

There was family litigation between the Chamberlaynes and the Drys, in 1720, in Chamberlayne v. Dry when Richard brought a case against Henry Dry senior, Henry Dry junior, John Dry and Mary Dry his wife, (Richard's own sister) Mary Dry and Elizabeth Dry (their children), infants, (by said John Dry, their father), [23]and another case in 1753 (Dry v Chamberlayne b.). [24]

Richard became High Sheriff of Essex on 22 Dec 1721, for one year. [25]

In 1724, he was paying an annual rent of £9. 11s. 8d. for his premises in Goat Court/King's Arms Court, Farringdon Without, just off Ludgate Hill (£1,112.70 purchasing power in 2017).

he brought litigation against the powerful Dutch de Neufville silk and linen merchant family; John de Neufville, Matthew de Neufville, Peter de Neufville and Isaac de Neufville. [26][27]

He was a supplier of silk to country landowners as well as to the wealthy in the city. On 29 October 1748, Sophia, Lady Newdigate wrote from Arbury to Mrs Elizabeth Palmer of Ladbroke:

- Dear Madam, I desired Miss Palmer to ask you whither you had not forgot ye lace of her Capucin, to which she yesterday received an answer that Mr. Chamberlayn says they are worn without, that ye stuff is not worth making up, and that I may do as I please about it. I must beg Mr. Chamberlayn and your pardons or saying I believe nobody ever yet wore them without some trimming, and he is very little likely to know as a silk mercer, for they neither sell lace or fringe. If the stuff is not worth making up, tis pity Mr. Palmer should be at ye expence of it, and for my self I had rather do nothing about it and therefore return you ye materials to put in what form you think proper, only disiring you to remember Molly has nothing of that kind to wear, and that this old one which like ye rest of her cloaths has been sent ragged for my maids to mend can have nothing more done to it. [28]

Marriage and Family

At the age of 34, Richard was able to marry Sarah, daughter of a wealthy, local landowner and his wife - Jeffery and Mary Stanes. [7] The Records of St Mary's Priory, Princethorpe show that the Chamberlaynes were involved in numerous business and property transactions between 1717 and 1833. Thomas Dummer of the Inner Temple, a renowned lawyer and conveyancer (b.1667, d. 26 Sep 1749) [29][30]was one of the parties to the marriage settlement between Richard and Sarah. Samuel Shepheard, Richard's great uncle, of the South Sea Company was another. Interestingly, it seems that the Dummer family would have dealings and connections with the Chamberlaynes for some time. The Chamberlaynes of Cranbury Park inherited the estate through marriage with the Dummer family.[31]

Richard and Sarah’s marriage took place at the church of St Stephen Walbrook and St Benet Sherehog, London, on 3 August 1717. Present at the wedding were Humfry Stanes, esq., Jeremiah Dummer, Esq, founder of Yale university and a distant cousin of Thomas's; Richard’s mother Mrs Jane Chamberlayne, Richard's sister, Bridget, a Mrs Rawson, a Mr William Goodgroom (who may have been the church organist) [32]and a Mr John Salter and his wife.[33]Salter may have been the John Salter who became Lord Mayor of London in 1739. He must have been a close associate of the family

|

| Marriage Record[34] |

In 1714, three years before Richard married Sarah, his future wife's father had bought an Inigo Jones-designed mansion, ‘The Ryes’, Hatfield Broad Oak, Essex from Dr Benjamin Woodroff[35] once Chaplain to Charles II. [36]The house stayed in the Chamberlayne family until it was eventually sold to John Archer Houblon of Great Hallingbury between 1834 and 1838.[37] in 1838, who would demolish it soon afterwards. [38]

|

| St Stephen Walbrook and St Benet Sherehog [39] |

The settlement is also recorded in The Princethorpe Foundation’s Archive Catalogue [7] and is interesting, as it involved relatives of Richard’s; an uncle, Francis Chamberlayne of London, Richard’s new father in law Jeffery, his father, Henry Stanes, and two cousins, Francis and Samuel II Shepheard, sons of Richard’s aunt Marie Chamberlayne. [40] Their father, Samuel Shepheard, Aunt Marie’s husband, had been M.P. for the City of London from 1705 to 1708, and was one of the founders and original directors of the new East India Company and head of the South Sea Company, and was described in 1710 as being …‘for shipping and foreign trade by far the first in England’. Three years after Richard and Sarah married however, the South Sea Bubble collapsed, ruining thousands of investors.

Jane Chamberlayne would have lived with her son and new daughter-in-law at Princethorpe until her death 14 years later. Richard must have had a house in London, however, because on 1 March, 1720, his son Stanes, named after Sarah's father, was born, and subsequently baptised just around the corner from where their London residence on Ludgate Hill was, in St Bride's Church, Fleet Street on 17 March. [41]The following Family Search record, however, shows another Stanes, baptised in the same place, the previous year. Perhaps it is a clerical error, since the day is the same, or perhaps this record refers to a previously born son, who died. [42]

After Jeffery Stanes died on 1 February 1731, Sarah, her father’s only child and heiress inherited The Ryes, and when Richard’s mother Jane died 11 months later on 29 December 1731, Richard and Sarah and their 11 year old son Stanes removed to Essex.

Some three years later, on 30 July 1734, when Richard and Sarah's son Staines was 14, he was, (with other unnamed parties - presumably his parents) defendant in a cause in relation to a Decree of the High Court in Chancery, in connection with the Will of his late grandfather Jeffrey Staines. It seems that Jeffrey had left debts and his creditors were seeking reimbursement. The case came before Thomas Bennett Esq.

|

| [43] |

- In pursuance of a decree of the High Court of Chancery, made in a Cause wherein John Salter Esq; and Thomas Salter, are Plaintiffs, and Staines Chamberlaine, an infant, and others, are Defendants, the Creditors, and Legatees of Jeffrey Staines, late of Ryes, in the Parish of Hatfield Broad-Oak, in Essex. Esq; deceased, are forthwith to come in and prove their debts before Thomas Bennett, Esq, one of the Masters of the said Court, at his House in Castle- Yard, Holborn, in order to have a satisfaction of the same, or in Default thereof such Creditors and Legatees will be excluded the benefit of the said Decree.[43]

Was the first plaintiff the same John Salter who had been present at Staines' parents' wedding and who was made Lord Mayor of London in 1739?

Property

|

| Private drive to Lofts Hall

Looking (through the gates) along the drive from Essex Hill. Gatehouse to the left. [44] |

A person of some standing in the county, Richard also owned the manor of Lofts Hall at Wendon Lofts, or Loughts, (which in 1670 had 21 hearths) [45]which he bought from the Mede family in 1720[46][47] and rebuilt in 1722. On 22 June 1731, the London Gazette carried a notice to say that the property was up for sale. This time the case was the responsibility of a John Bennett Esq of the High Court.

|

| The Gazette - 22 June 1731 |

- To be peremptorily Sold before John Bennett Esq, one of the Masters of the High Court of Chancery, pursuant to a Decree of the said Court, on Friday the 30th of July next, at five of the Clock in the Afternoon, the Freehold Estate of Richard Chamberlayne Esq, situate in Lofts and Elmdon, in the County of Essex, consisting of a large Mannor (sic) House and four Acres of Gardening, new walled and planted with the best Fruits, with new Coach houses, and Stables for Twenty Horses, with several large Fish Ponds therein, well stored with Fish, adjoyning to a Common with a fine Turf to sweat Horses on, with several Farmes adjyning thereto; in the whole upwards of 520l per Annum, which, if enclosed, as it is in the power of the Owner so do (sic) do, will be double the Value, being very rich Land, and producing Saffron after once set for many years together; there was formerly a Park set round the House, which with little expense may be made so again, the Air and Situation is very healthful and pleasant, it is situated about three Miles out of the great Road from London to New-Market, three from Saffron Waldon, and five from Royston, 10 from Cambridge, 10 from New-Market, and 30 from London, particulars whereof may be had at the said Master's House in Chancery Lane.[48]

What is astonishing is that Wendon Tofts had once been the house of Sir John Mede, [53]whose daughter Elizabeth had married, as her second husband, another Richard Chamberlayne, this Richard's second cousin once removed. Is it too far out to imagine that he had known this? He would have had the deeds of the house and known its history. Gentlemen of that day, interested in antiquities, as Richard's forbears had been, were keen to discover their own family lineage and history. Wendon Tofts was demolished in 1938 and replaced with a new building.[54]

|

| Hicks Hall Magistrates Court[55] |

Justice of the Peace

Richard became a Justice of the Peace for Middlesex at Islington. Court sessions were held at Hicks Hall, [56][57] at the southern end of St John's St, Clerkenwell. Only 17 years before Richard was born, on 9 October 1660, a grand jury had convened there to try 29 of the men who had signed the death warrant of Charles I. [58] Samuel Pepys mentioned it in his diary entry for 6 December 1660.

- Before I went forth this morning, one came to give me notice that the Justices of Middlesex do meet tomorrow at Hickes hall and that I, as one, am desired to be there; but I fear I cannot be there, though I much desire it. [59]

In August[60] and September 1750, Richard presided over various cases in which petty criminals were tried for stealing money and other valuables. [61]

|

| [62] |

On 14 August:

- Last Night, about Eight o‘ Clock, as Richard Chamberlayne Esq; one of his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace for the County of Middlesex, was returning in his Chariot from Hamstead (sic) to his House at Islington, he was attack’d at Lower Holloway, near Islington Workhouse, by a single Highwayman, who robb’d him of near £3 (equivalent of £350.01 in 2017) The Villain attempted to shoot the Coachman, for not stopping so soon as he would have had him, but the Pistol only flash’d in the Pan. [63]

The following year, 1751, the Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal reported on Wednesday 21 August:

- Yesterday, Mary Graves, a very noted and beautiful Courtesan, was committed, by Richard Chamberlayne, Esq; to New-Prison, for picking the Pocket of a Gentleman who had been the same evening regaling with the Lady at a Tavern in Catherine-Street.[64]

The General Evening Post in August 1755 reported on the outcome of a murder case, in which Richard committed a coachman to Newgate gaol for intentionally running over a Mr Ashmore, undertaker and on 4 June 1757, the London Chronicle reported the sentence of a soldier for armed robbery.

|

| [68] |

|

| [69] |

(Hicks Hall was demolished in 1782, and the site is marked by a traffic island in the middle of the street today.)[70][71]

Death and Burial

Sarah died on 10 January 1742 at the age of 50.

|

| Richard Chamberlayne Cartouche |

Richard passed away eight years later on 28 March 1758. [72]

|

| [73][74] |

They are both buried in St Mary’s, Hatfield Broad Oak, Essex, with Richard's 14th great grandfather, Robert de Vere, 3rd Earl of Oxford, [75][76]and are commemorated by two classical wall monuments inside the church. [77]

|

| St Mary's Hatfield Broad Oak wall memorial Richard Chamberlayne [78] |

Richard's name also appears in "The Names and Descriptions of the Proprietors of Unclaimed Dividends... Etc". His single dividend became payable in July 1757 and remained unpaid in 1800.[79]

Research

One Dick Adams, later a highwayman, pretended to be the Bishop of London's nephew in order to escape from a silk mercer (on Ludgate Hill, who had done business with St James' Palace) whom he had robbed. Adams was executed at Tyburn in 1713. This can't have been Richard Chamberlayne, who only moved to Ludgate Hill in 1714. Retrieved from British Executions (Here;) and (Here;) Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

Sources

- ↑ Morant, Philip., (1768)., The history and antiquities of the county of Essex. Compiled from the best and most ancient historians; ... In two volumes. ... Vol 2 Illustrated with copper plates: Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 1 May 2024.

- ↑ Business, Society and Family Life in London, 1660–1730, Earle, Peter.,UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1989 The Regents of the University of California, The Making of the English Middle Class: Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 28 May 2021.

- ↑ Nicolson, Adam, Gentry, Six Hundred Years of a Peculiarly English Class, HarperPress 2011

- ↑ London Lives, Crime, Poverty and Social Policiy in the Metropolis 16690-1800, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Warwickshire County Record Office; Warwick, England; Warwickshire Anglican Registers; Roll: Engl/2/1041; Document Reference: DR 108, Source Information Ancestry.com. Warwickshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1535-1812 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Warwickshire Anglican Registers. Warwick, England: Warwickshire County Record Office. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Richard Chamberlain in 1683, Warwickshire Baptisms, Stretton-On-Dunsmore, Warwickshire, England. Retrieved from Find My Past (Here;) Accessed 16 Dec 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Assignment to attend the uses of a marriage settlement between Francis Chamberlayne, Robert Huntman, Richard Chamberlayne, Samuel Shepheard, Francis Shepheard, Jeffery Stanes, Sir Gregory Page, Thomas Dummer and Henry Stanes of lands in London, 2nd Aug 1717. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ecclesiastical Commissioners J.G. & F. Rivington, 1837 - Appendix No 1, pp25-32, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 18 Nov 2020.

- ↑ Rugby school register: with annotations and alphabetical index. Entrances in 1691. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (p.8;) Accessed 1 Apr 2022.

- ↑ Ed. Salzman, L. F., (1951). Parishes: Stretton-upon-Dunsmore and Princethorpe, in A History of the County of Warwick: Knightlow Hundred, (Vol. 6, pp. 241-245). London: British History Online, Retrieved from British History Online (Here;) Accessed 18 Nov 2020.

- ↑ Journals of the House of Commons, Volume 11, Great Britain House of Commons H.M. Stationery Office, 1693. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 18 Nov 2020.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. John Rudyard. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. February 12, 2020, 20:23 UTC. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Boase, George Clement., Courtney, William Prideaux., (1878)., Bibliotheca Cornubiensis, A Catalogue of the Writings, Both Manuscript and Printed of Cornishmen, and of Works Relating to the County of Cornwall. P-Z · (Vol. 2. p.606)., Retrieved from Google e-books [Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ The Mercers Company. Intriguing History. Retrieved from Intriguing History (Here;) Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

- ↑ Calendar of Treasury Papers, 1556-7--[1728]: 1708-1714. (1879)., Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. Retrieved from Google e-Books (Here;) Accessed 20 July 2022.

- ↑ The New England Historical and Genealogical Register (1881)., Retrieved from Google e-Books (Here;) Accessed 20 July 2022.

- ↑ The Spectator 1714-10-27: Vol 1-8 Iss 613. Freely available from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

- ↑ From the Free Internet Repository: "John Rocque's Map of London, 1746," (D2). Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (Here;) Accessed 7 Dec 2022,

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Find My Past. Royal Household Staff 1526-1924. Retrieved from Find My Past (Here;) Accessed 5 Feb 2023.

- ↑ Rothstein, Natalie, The silk industry in London, 1702-1766, Thesis (MA), University of London (1961). Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

- ↑ Hampton Court Richard Roberts Stool for the Hampton Court Bedchamber: Silk damask supplied by John Johnson or Richard Chamberlayne. (Here;) Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

- ↑ Bird, Rufus. “The Furniture and Furnishing of St James's Palace 1714-1715.” Furniture History 50 (2014): 147–203. Retrieved from Jstor (Here;) Accessed 19 July 2022. Also retrieved from academia edu (Here;) Accessed 19 July 2022.

- ↑ The National Archives, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Discovery. The National Archives. Dry v Chamberlayne b., 1753. Ref: C 12/1858/34. Retrieved from the National Archives (Here;) Accessed 25 Oct 2022.

- ↑ The High Sheriff of Essex. List of High Sheriffs of Essex. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

- ↑ The National Archives, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Jan de Vries, Ad van der Woude, Professor of Rural History Ad Van Der Woude, Cambridge University Press, 28 May 1997, The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500-1815, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Hervey, Sydenham Henry Augustus., (1914)., Ladbroke and its Owners. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (p.226-227;) Accessed 9 Sept 2022.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. Thomas Lee Dummer, only son of Thomas Dummer, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. May 10, 2021, 19:32 UTC. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ The New England Historical and Genealogical Register: Volume 35 1881, New England Historic Genealogical Society Heritage Books, 1996, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ John Burke, Bernard Burke H. Colburn, 1847, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, Volume 1 Retrieved from [1] Accessed 22 May 2021

- ↑ Dictionary of Composers for the Church in Great Britain and Ireland Humphreys, Maggie, Evans, Robert, (1997).,Dictionary of Composers for the Church in Great Britain and Ireland. A&C Black. Retrieved from Google books (Here;) Accessed 20 Mar 2022.

- ↑ Bannerman, W. Bruce (William Bruce), Bannerman, William Bruce, Jr. (1919)., St. Stephen's, Walbrook, with St. Benet Sherehog (Parish : London); The registers of St. Stephen's, Walbrook, and of St. Benet Sherehog, London. London: Roworth and Co. Ltd. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (p.149;) Accessed 20 Mar 2022.

- ↑ Bannerman, W. Bruce (William Bruce), Bannerman, William Bruce, Jr. (1919)., St. Stephen's, Walbrook, with St. Benet Sherehog (Parish : London); The registers of St. Stephen's, Walbrook, and of St. Benet Sherehog, London. London: Roworth and Co. Ltd. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (p.149;) Accessed 20 Mar 2022.

- ↑ British History Online, Victoria County History. 'Parishes: Hatfield Broad Oak', in A History of the County of Essex: (Vol. 8). Ed. Powell, W.R., Board, Beryl A., Briggs, Nancy,. Fisher, J.L., Harding, Vanessa A., Hasler, Joan., Knight, Norma & Parsons, Margaret., (1983 pp. 158-186). London: British History Online. Retrieved from British History Online (Here;) Accessed 18 Nov 2020.

- ↑ Benjamin Woodroffe of the Greek College. Retrieved from Oxoniensia (Here;) Accessed 18 Nov 2020.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. John Archer-Houblon. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. May 22, 2021, 02:13 UTC. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ 'Parishes: Hatfield Broad Oak', in A History of the County of Essex: Volume 8, ed. W R Powell, Beryl A Board, Nancy Briggs, J L Fisher, Vanessa A Harding, Joan Hasler, Norma Knight and Margaret Parsons (London, 1983), pp. 158-186. British History Online, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 2 Dec 2020.

- ↑ From the Free Internet Repository: Wikipedia contributors. St Stephen Walbrook. Retrieved from Wikipedia (Here;) Accessed 7 September 2021.

- ↑ History of Parliament Online, Samuel Shepheard. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 18 Nov 2020.

- ↑ Baptism of Stanes Chamberlayne, 17 Mar 1720. Retrieved from FamilySearch (Here;) Accessed 18 Nov 2020.

- ↑ Baptism record for Stanes Chamberlain (sic) 17 Mar 1719. Retrieved from FamilySearch (Here;) Accessed 17 Nov 2020.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 The London Gazette. 30 July 1734. (Issue:7320, Page:3). Retrieved from the Gazette (Here;) Accessed 5 Feb 2023.

- ↑ © Copyright Trevor Harris and licensed for reuse under creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0. Retrieved from Geograph (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- ↑ Essex Hearth Tax Return Michaelmas 1670. Essex Hearth Tax Online. Retrieved from Doczz net (Here;) Accessed 20 Sept 2022.

- ↑ Essex Record Office. 3 July 1720. Reference: D/DB 697. Richard Chamberlayne of London mercer, to William Pitches of Wendon Lofts, gent., and wife Margaret, and John Whalley of New North Street in parish of St.Andrew Holborn, Middlesex) merchant, and wife Jane (who, with said Margaret, is daughter and coheiress of John Mede of Wendon Lofts). Retrieved from Essex Record Office (Here;) Accessed 6 Sept 2022.

- ↑ Ed. Gomme, George Laurence, (1883-1905)., The Gentleman's magazine library: being a classified collection of the chief contents of the Gentleman's magazine from 1731 to 1868. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- ↑ The Gazette. Publication date: 22 June 1731. (Issue:6998, p.2). Retrieved from The Gazette (Here;) Accessed 5 Feb 2023.

- ↑ Munroe, Bruce, (2009), Some Stately Homes of North-west Essex. Saffron Walden Historical Journal. Retrieved from SWHS (Here;) Accessed 5 Feb 2023.

- ↑ Wenden Lofts, (1916)., in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, (Vol. 1, pp. 328-329). North West. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved from British History Online (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- ↑ Wright, Thomas. (1836). County Of Essex (Vol. 2, p.176). London: George Virtue. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- ↑ Great Britain. (1916)., Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments and Construction of England An inventory of the historical monuments in Essex. Vol.1. p.239. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (here;) Accessed 20 Sept 2022.

- ↑ Cave, E. (1857). The Gentleman's Magazine Or, Monthly Intelligencer for the Year ... By Sylvanus Urban (Google eBook). Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 5 Mar 2023.

- ↑ Lost Heritage. England's Lost County Houses. Lofts Hall. Retrieved from Lost Heritage (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. Hicks Hall. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. March 14, 2021, 14:56 UTC. Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Ed. Cordy Jeaffreson, John., (1892). Sir Baptist Hicks, in Middlesex County Records: 1667-88, (Vol. 4, pp.329-349). London: Middlesex County Record Society. Retrieved from British History Online (Here;) Accessed September 11 2021.

- ↑ Wood engraving published c.1872. Retrieved from (Here;) 17 October 2020.

- ↑ Bayly Howell, Thomas,. (1816)., A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors from the Earliest Period to the Year 1783, Vol. 5, p.981-f).T.C. Hansard. Retrieved from Google Books (Here;) Accessed 10 Sept 2021.

- ↑ The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Daily entries from the 17th century London diary. Thursday 6 December 1660. Retrieved from Diary of Samuel Pepys (Here;) Accessed 10 Sept 2021.

- ↑ London Lives 1690-1800. Middlesex Sessions: Sessions Papers - Justices' Working Documents. Retrieved from London Lives (Here;) Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

- ↑ London Lives 1690-1800. Middlesex Sessions: Sessions Papers - Justices' Working Documents. Retrieved from London Lives (Here;) Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

- ↑ Freely available from the free media repository: Wikimedia Commons contributors. File: The XVIIIth century; its institutions, customs, and costumes France, 1700-1789 (1875) (14594646349).jpg. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, (Here;) Accessed 23 March 2023.

- ↑ British Newspaper Archive. Sat 18 Aug 1750, Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal. Retrieved (with subscription) from BNA (Here;) Accessed 23 Mar 2023.

- ↑ British Newspaper Archive. Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal - Wednesday 21 August. Retrieved (with subscription) from BNA (Here;) Accessed 23 Mar 2023.

- ↑ The Twickenham Museum. The history centre for Twickenham, Whitton, Teddington and the Hamptons. Retrieved from The Twickenham Museum (Here); Accessed 10 Sept 2021.

- ↑ A Complete Collection of State-trials, and Proceedings for High-treason, and Other Crimes and Misdemeanours, (Vol.19. pp.680-692). The Case of Ashley and Simons the Jew. (Jan 1816)., London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. Retrieved from Google Books (Here;) Accessed 10 Sept 2021.

- ↑ Howell, Thomas Bayly., Howell, Thomas Jones., Jardine, David., (1816)., London : Printed by T.C. Hansard for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Browne : (J.M. Richardson : Black, Parbury, and Allen : Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy : E. Jeffery : J. Hatchard : R.H. Evans : J. Booker : E. Lloyd : J. Booth : Budd and Calkin : T.C. Hansard). A complete collection of state trials and proceedings for high treason and other crimes and misdemeanours from the earliest period to the year 1783: with notes and other illustrations. Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 5 Mar 2023.

- ↑ The London Chronicle., (Vol. 1. Jan-30 June 1757). Retrieved from Google Books (Here;) Accessed 28 May 2021.

- ↑ Freely available from: The General Evening Post: 1755. Retrieved from Google e-Books (Here;) Accessed 5 May 2024.

- ↑ Obituary Prior to 1800: (as Far as Relates to England, Scotland, and Ireland) 1899, Harleian Society, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ London Lives, Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the Metropolis 16690-1800, Retrieved from (Here;) Accessed 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Ed. Cave. E. (1758). The Gentleman's Magazine, (Vol. 28, p. 146). Retrieved from Google Books (Here;) Accessed 9 Sept 2021.

- ↑ R. Baldwin, 1758, The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer, Vol. 27. Retrieved from Google e-Books (Here;) Accessed 28 May 2021.

- ↑ Musgrave, William, Sir, (1899)., Obituary prior to 1800 (as far as relates to England, Scotland, and Ireland. (Vol.44, p.373). Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 24 Oct 2022.

- ↑ WikiTree Relationship Finder: Robert de Vere - Richard Chamberlayne. Retrieved from WikiTree Relationship Finder (Here;) Accessed 9 Sept 2021.

- ↑ Church Monuments Gazetteer. Essex (2). Retrieved from Church Monuments Gazetteer (Here;) Accessed 9 Sept 2021.

- ↑ Walford, Edward, Apperson, George Latimer., Cox, John Charles., (1892). The Antiquary. Vol. 26. Retrieved from Google e-Books (Here;) Accessed 18 July 2022.

- ↑ From the Free Internet Repository: Image © Acabashi; Creative Commons CC-BY-SA 4.0; Source: Wikimedia Commons. File:Church of St Mary Hatfield Broad Oak Essex England - Richard Chamberlayne wall monument.jpg. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (Here;) Accessed 20 November 2020.

- ↑ Bank of England, (1800)., The Names and Descriptions of the Proprietors of Unclaimed Dividends on Bank Stock, and on the Public Funds, Transferable at the Bank of England, which Became Due on and Before the 5th July 1797, and Remained Unpaid on the 1st October 1800, Etc. Bank of England., Treasury Office, South Sea House. (p.48). Retrieved from Google Books (Here;) Accessed 13 Sept 2021.

Further Reference

- Short title: Salter v Chamberlayne. Document type: Bill and three answers. Plaintiffs:...Reference: C 11/695/6. Retrieved from Discovery: The National Archives (Here;) Accessed 12 Dec 2022.

- Princethorpe: Retrieved from The Old Princethorpian (Here;) Accessed 1 Apr 2022.

- Records of St. Mary's Priory from its foundation in 1832 to its closure in 1966. Retrieved from St Mary's Priory (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- Report of Annual Meeting. Chamberlain Association of America (1902). Retrieved from the Internet Archive (Here;) Accessed 2 Apr 2022.

- Wotton, Thomas., (1741). The English Baronetage: Containing a Genealogical and Historical Account of All the English Baronets, Now Existing: Their Descents, Marriages, and Issues...; Retrieved from Google Books (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- Burke, John., Burke, Bernard., (1844)., A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Extinct and Dormant Baronetcies of England, Ireland, and Scotland. Pub. W. Clowes. Retrieved from Google Books (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- William III King of England. Retrieved from Wikipedia (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- Justices of the Peace and the Pre-Trial Process. Retrieved from London Lives (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

- (Here;) Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

- (Here;) Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

- (Here;) Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

- and for other R.C cases, see (Here;) Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

- Farrell, William (2014) Silk and globalisation in eighteenth century London: commodities, people and connections c.1720-1800. [Thesis] (Unpublished). Retrieved from eprints (Here;) Accessed 2 May 2024.

- Spitalfields Life., John Thomas Smith’s Ancient Topography. Retrieved from Spitalfields Life (Here;) Accessed 8 Sept 2021.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Kate Higgins, Consultant Cataloguer, The Mercers’ Company, 6, Frederick’s Place, London, EC2R 8AB., (Here;) for ascertaining that Richard was never a member of the Mercers' Company, (via E-mail, 28 May 2021).

No known carriers of Richard's DNA have taken a DNA test. Have you taken a test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Featured Eurovision connections: Richard is 36 degrees from Agnetha Fältskog, 23 degrees from Anni-Frid Synni Reuß, 30 degrees from Corry Brokken, 24 degrees from Céline Dion, 24 degrees from Françoise Dorin, 23 degrees from France Gall, 23 degrees from Lulu Kennedy-Cairns, 29 degrees from Lill-Babs Svensson, 21 degrees from Olivia Newton-John, 31 degrees from Henriette Nanette Paërl, 33 degrees from Annie Schmidt and 18 degrees from Moira Kennedy on our single family tree. Login to see how you relate to 33 million family members.

C > Chamberlayne > Richard Chamberlayne JP

Categories: Warwick, Warwickshire | Princethorpe, Warwickshire | Silk Merchants | St Stephen Walbrook Church, City of London | St Brides, Middlesex | Lofts Hall, Wenden Lofts | Justices of the Peace | Chamberlayne Name Study