Biography

Conflicting Biographies

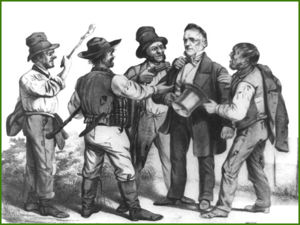

John Murrell was the son of a traveling Methodist minister and a criminally ambitious tavern-keeper known as "Mom Murrell," whose legend grew larger than life as the "Great Western Land Pirate." A horse thief, Natchez Trace Bandit, Mississippi River Marauder, Counterfeiter, Convict, Highwayman, Criminal Gang (aka so-called "Mystic Clan") leader, and a menace (if not to slavery itself), to those already living the nightmare of slavery in America; Murrell was also a son, husband, father, carpenter, then, finally, a blacksmith (of such skill as was imparted during a decade behind bars, where he, himself, was branded with an "H" for "horse thief"). [citation needed]

From Life on the Mississippi, [a fictionalized account] by Mark Twain:

There is a tradition that Island 37 was one of the principal abiding places of the once celebrated 'Murel's Gang.' This was a colossal combination of robbers, horse-thieves, negro-stealers, and counterfeiters, engaged in business along the river some fifty or sixty years ago. While our journey across the country towards St. Louis was in progress we had had no end of Jesse James and his stirring history; for he had just been assassinated by an agent of the Governor of Missouri, and was in consequence occupying a good deal of space in the newspapers. Cheap histories of him were for sale by train boys. According to these, he was the most marvelous creature of his kind that had ever existed. It was a mistake. Murel was his equal in boldness; in pluck; in rapacity; in cruelty, brutality, heartlessness, treachery, and in general and comprehensive vileness and shamelessness; and very much his superior in some larger aspects. James was a retail rascal; Murel, wholesale. James's modest genius dreamed of no loftier flight than the planning of raids upon cars, coaches, and country banks; Murel projected negro insurrections and the capture of New Orleans; and furthermore, on occasion, this Murel could go into a pulpit and edify the congregation. What are James and his half-dozen vulgar rascals compared with this stately old-time criminal, with his sermons, his meditated insurrections and city-captures, and his majestic following of ten hundred men, sworn to do his evil will! [1]

From Encyclopedia of Arkansas, "John Andrews Murrell" (1806–1844):

Among legendary characters associated with nineteenth-century Arkansas, John Andrews Murrell occupies a prominent place. Counterfeiting and thieving along the Mississippi River, Murrell was only a petty outlaw in a time and place with little law enforcement. However, he became a greater figure in legend following his death... born in Lunenburg County, Virginia, in 1806. His father, Jeffrey Gilliam Murrell, was a respected farmer who, with his wife, Zilpha Murrell, raised eight children. Shortly after John was born, the Murrells and other relations moved to Williamson County, Tennessee. However, Murrell’s father fell on hard times, and his sons, who were wild and errant, began to have trouble with the law. At the age of sixteen, Murrell, along with brothers William Murell and Jeffrey Gilliam Murell Jr., were charged with “riot” (disturbing the peace). In February 1823, Murrell was charged with horse theft. He languished in jail for several months before being tried and sentenced (after the fashion of that day) to thirty lashes, the pillory, branding, and one year in prison. The elder Murrell died in 1824, leaving Zilpha to care for her wayward brood. She moved farther west through Tennessee, first to Wayne County, and, finally, to Denmark in Madison County. Murrell, who was released from jail in 1827, married Elizabeth Mangham, who bore him two children...Murrell became a model prisoner, read the Bible, and learned the blacksmithing trade. When he contracted tuberculosis, he was granted early release in April 1844. He died in Pikeville, Tennessee, on November 1, 1844.[2]

From Notes From Under Grounds, by David Whitesell:

Born in Virginia ca. 1806, John Murel (or Murrell) grew up in Tennessee, where he and his brothers pursued lives of crime. Murel’s gang was most active along the Natchez Trace—the trail winding southwest from Nashville down to Natchez on the Mississippi River. His criminal activities all but ended in 1835 when Murel began a ten-year jail term, but his legend was just beginning. The chief trial witness, one Virgil Stewart, promptly published under a pseudonym this sensationalist (and mostly fictional) biography, in which he identified Murel as head of a 455-member “mystic clan” masterminding a national slave insurrection planned for December 25, 1835. Stewart’s warning was widely believed in the South and provoked a series of deadly vigilante actions. Murel’s legend lives on in such venues as Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer, short stories by Jorge Luis Borges and Eudora Welty, and even a Hollywood western starring Humphrey Bogart.[3]

From Wikipedia: "John Murrell (bandit):"

The Murrell Excitement... Virgil Stewart, in 1835, wrote an account of a Murrell sponsored slave rebellion plot sponsored by highwaymen and Northern Abolitionists. The account was thought to be fictitious. The account was published as a pamphlet called 'A History of the Detection, Conviction, Life And Designs of John A. Murel, The Great Western Land Pirate; Together With his System of Villany and Plan of Exciting a Negro Rebellion, and a Catalogue of the Names of Four Hundred and Forty Five of His Mystic Clan Fellows and Followers and Their Efforts for the Destruction of Mr. Virgil A. Stewart, The Young Man Who Detected Him, To Which is Added Biographical Sketch of Mr. Virgil A. Stewart.' Stewart wrote this so-called "confession of John Murrell" under the pseudonym of 'Augustus Q. Walton, Esq.,' for whom he invented a fictitious background and profession. Some historians assert that Stewart's pamphlet was largely fictional, and that Murrell (and his brothers) were at best inept thieves, having bankrupted their father over the years for bail money.... However, many of the claims made in the pamphlet were believed at the time in some parts of the South, and led to the "Murrell Excitement." During this time, there was increased tension between the races and between locals and outsiders. On July 4, 1835, there were disturbances in the red-light districts of Nashville, Memphis and Natchez and twenty slaves and ten white men where hanged after confessing to complicity in this plot. On July 6, in Vicksburg, an angry mob decided to expel all professional gamblers from the town, based on a rumor that the gamblers were part of this plot. The gamblers resisted, and as a result, 5 gamblers were hanged by the mob... The following claims were originally derived from Stewart's "History..." of John A. Murel.... While in the Tennessee State Penitentiary, John Murrell, as part of his reform, was required to work and learned the blacksmith trade. A decade in prison, starting in 1834, under the Auburn penitentiary system, of mandatory convict regimentation, through prison uniforms, lockstep, silence, and occasional solitary confinement, broke Murrell mentally and supposedly left him an imbecile. He spent the last months of his life, as a blacksmith in Pikeville, Bledsoe County, Tennessee. The Nashville Daily American newspaper mentioned a different account of his last year of life, that, upon his release from prison, at 38 years old, he became a reformed man, a Methodist in good standing, was a carpenter by trade... In a deathbed confession, Murrell admitted to being guilty of most of the crimes charged against him except murder, to which he claimed to be "guiltless." John A. Murrell died on November 21, 1844, just nine months after leaving prison, having contracted "pulmonary consumption," now known as tuberculosis.'" [4]

From History of Tennessee: The Making of a State:

John A. Murrell and the Reign of Disorder: His mother was a woman of evil disposition, teaching him his first lesson in vice, by the time he was of age he had become a confirmed evil-doer; and formally adopted robbery as a profession... He knew no degrees in crime, and regarded murder as in no wise more heinous or repugnant than the theft of a watch. He never robbed a man, unless by stealth, without killing him, and he never robbed by violence where the person robbed could not be killed.[5]

From Robert E. Howard, Two Gun Raconteur, "The Hellbender, John A. Murrell," by Keith Taylor:

Robert E. Howard had a powerful interest in the desperadoes of his native southwest. “I could fill a thick volume of such disconnected bits and still not exhaust my chaotic store,” he wrote to H.P. Lovecraft in June 1931. I’ve found that passion expressed again and again in his letters... REH certainly viewed with a blend of fascination and horror the career of John A. Murrell. His letter – the June 1931 missive mentioned above, to Lovecraft – describing it, contains some of his most eerie and evocative writing outside his horror stories. Perhaps even including those: "Murrell was a hellbender, in Southwest vernacular. He planned no less than an outlaw empire on the Mississippi river, with New Orleans as his capital and himself as emperor. Son of a tavern woman and an aristocratic gentleman, he seemed to have inherited the instincts of both, together with a warped mind that made him as ruthless and dangerous as a striking rattler." Zilphia, nee Andrews, had been the daughter of a prosperous Virginia planter... genteel and accepted. She hadn’t been “a tavern woman” all her life; she inherited the inn from her parents. John A’s ancestors on both sides came from the state’s early landed families. Not a lawbreaker or ne’er-do-well in generations. The moral decline in the family began with Zilphia. She managed the inn (near Columbia, Tennessee), since her preacher husband was often away giving sermons.... Poor old Jeffrey didn’t know the half of it. To put it bluntly, the voluptuous Zilphia was a bigger harlot than Rahab. She was also a thief to match any in Fritz Leiber’s "Lankhmar," and she taught her four sons to assist her. Male travelers with bulging purses were given the come-on by “Mom Murrell,” and she would whore with them while William, her eldest, or another son, took their coin, watches, and anything else worth having. They weren’t likely to complain later. It would have meant admitting in court that they’d paid the preacher’s wife for sex, and “Mom Murrell” would surely have denied it with a scandalized face, backed by her kids, well coached to appear wild with outrage at the slur on their mother’s honor.... The Murrells were a strikingly good-looking family. The notorious John had a splendid appearance, and his sister, Leanna Murrell (one of three or four girls) was both a beauty and a superb dancer.[6]

From Ancestry's Rootsweb:

John Andrews Murrell... His father and uncle, Drury, posted bond for him... John A. Murrell was received in the Penitentiary August seventeenth one thousand eight hundred & thirty four he is five feet ten inches & a half in height & weighs from one hundred & fifty eight to one hundred & seventy pounds dark hair blue eyes long nose & much pitted with the smallpox tolerably fair complexion twenty eight years of age Born in Lunenburgh County Virginia & brought up in Williamson County Tennessee his mother wife and two children reside in the neighborhood of Denmark about nine miles from Jackson Madison county Tennessee his wife's maiden name was Mangham her connexion reside on the waters of South Harpeth Williamson Co. Tennessee. His Brother Wm. S. Murrell a Druggist resides in Cincinnatti Ohio he has another brother living in Sumpter County S. Carolina he has a scar on the middle joint of the finger next to the little finger of the left hand & one on the middle finger of the same hand a scar on the inside of the end of the finger next the little finger of the right hand has generally followed farming was found guilty of Negro stealing at the Circuit Court of Madison County & sentenced to Ten Years confinement in the jail & penitentiary House of the State of Tennessee." (from the 1831-1842 Prison Record Book, Tennessee State Archives) When he was released (April 18, 1844)... John A. Murrell's Cell---While inspecting the records of the penitentiary yesterday, records grown musty and yellow with age, an American reporter came across an entry concerning a noted individual, whose name, fifty years ago, was a terror, not only to Middle Tennessee, but to the entire State. The individual referred to was John A. Murrell, and the entry that startled the reporter, as he nervously clutched the page, was the notation made on the records when Murrell was received at the penitentiary in 1834 for stealing a negro in Madison County. The entry, as it appears on the penitentiary records, is as follows: "John A. Murrell was received in the penitentiary August 17, 1834. He is five feet ten inches and a half in height, and weight from 158 to 170 pounds, dark hair, blue eyes, long nose and much pitted with the small- pox, tolerably fair complexion, twenty-eight years of age. Born in Lunenburg County, Virginia, and brought up in Williamson County, Tennessee. His mother, wife and two children reside in the neighborhood of Denmark, about nine miles from Jackson, Madison County, Tennessee. His wife's maiden name was Manghan. Her connections reside on the waters of South Harpeth, Williamson County, Tennessee. His brother, William S. Murrell, a druggist, resides in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has another brother living in Sumsterville, S.C. He has a scar on the middle joint of the finger next the little finger of the right hand. Has generally followed farming. Was found guilty of Negro stealing at the Circuit Court of Madison County and sentenced to ten years confinement in the jail and penitentiary house of the State of Tennessee." On the margin of the record is indorsed: "John A. Murrell was delivered to J.S. Lyon, Sheriff of Madison County, 9th April 1837. See order of Court of Errors and Appeals, at Jackson, filed with convict record, 1834." And below this appears the entry: "Returned April 26, 1837, by order of Court of Appeals." Murrell was discharged at the expiration of his time, but no entry appears on the penitentiary books showing the date of his discharge. While an inmate at the penitentiary, Murrell learned the blacksmith trade and followed it during the time of his imprisonment. He occupied the second cell from the entrance in wing No. 2. The cell was inspected by the reporter, but any marks of Murrell's occupancy that may have existed have disappeared beneath the white-wash that has been applied scores of times since Tennessee's noted highwayman called the cell his own nearly fifty years ago. [7]

From Flush Times & Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson, by Joshua D. Rothman:

In 1834 Virgil Stewart rode from western Tennessee to a territory known as the "Arkansas morass" in pursuit of John Murrell, a thief accused of stealing two slaves. Stewart's adventure led to a sensational trial and a wildly popular published account that would ultimately help trigger widespread violence during the summer of 1835, when five men accused of being professional gamblers were hanged in Vicksburg, nearly a score of others implicated with a gang of supposed slave thieves were executed in plantation districts, and even those who tried to stop the bloodshed found themselves targeted as dangerous and subversive. Using Stewart's story as his point of entry, Joshua D. Rothman details why these events, which engulfed much of central and western Mississippi, came to pass. He also explains how the events revealed the fears, insecurities, and anxieties underpinning the cotton boom that made Mississippi the most seductive and exciting frontier in the Age of Jackson.[8]

From Journals: The Author 2016: Review of Flush Times & Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson, by Joshua D. Rothman:

In 1853 Joseph G. Baldwin's The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi provided a rollicking account of the boosterism and self-making that had accompanied the settlers' appropriation of Native American lands there. Joshua Rothman's new book pays homage in more than just title to Baldwin's vision, although Rothman emphasizes the darker, more sinister aspects of the boom mentality in the new cotton states. To explore this speculative frenzy, Rothman focuses on the cases of Virgil Stewart, chronicler of the “land pirate” John Murrell; the rumored slave insurrection of 1835; and the Vicksburg anti-gambling riot that same year... the book that Stewart published under a pseudonym further embellished....[9]

From Daily Beast:

The cotton boom brought anxieties over social disorder embodied by a man named John Murrell, the great Western land pirate. Murrell was a horse thief and slave stealer who swindled his way through the Deep South in the early 1830s. He became a household name after the publication of a sensational pamphlet that placed him at the head of a secret conspiracy to incite a massive slave insurrection across the South on Christmas Day in 1835 and rob all the banks as the country went up in flames. Tarantino’s plot seems tame in comparison to the pulp fiction of Jacksonian America. The problem was that some people believed it. Not long after the pamphlet appeared, nervous white folks in central Mississippi caught wind of hearsay about an impending slave uprising in their neighborhood. Confessions were whipped out of slaves pegged as suspects, and then they were hanged. Nobody knows how many slaves were killed; the number is probably in the dozens. The slaves’ confessions fingered a few local white men who happened to be notorious in the community for being too friendly to black people. A self-constituted committee of the area’s best men, “unclothed with the forms of law,” tried the white men on the basis of evidence that could never have been admitted in a real courtroom: the confessions that had been whipped out of slaves who were now dead. But fear and vengeance trumped legal niceties. The committee convicted and hanged five of them—two on the Fourth of July. At least one confessed to being part of the Murrell clan, but another luckless fellow whom the committee called an abolitionist assured his wife on the day before he died, “I can meet my God innocently.” Meanwhile, not too far away in Vicksburg, Mississippi, the ritual purification of a society tainted by Murrellism targeted the town’s gamblers. A melee on Independence Day led the town’s respectable people to break up the gaming tables and oust its lowlifes. When a prominent doctor was gunned down during the sweep, a righteous mob seized five desperadoes held responsible for the crime and lynched them. [10]

From Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama, 1800-1840:"

Murrell became adept at using the enticement of freedom to steal slaves.... [11]

From Ancestry: Fold 3, "John Murrell and the 1835 slave revolt:"

In his Historic Blue Grass Line, Douglas Anderson tells of Murrell having been tried in Nashville on a change of venue, on May 25, 1825, on the charge of having stolen a horse from a widow in Williamson County. The verdict and judgment was that Murrell should serve twelve months' imprisonment; be given thirty lashes on his bare back at the public whipping post; that he should sit two hours in the pillory on each of three successive days; be branded on the left thumb with the letters H. T. in the presence of the Court, and be rendered infamous. Mr. Anderson describes the branding from the statement of an eye-witness as follows: 'At the direction of the sheriff Murrell placed his hand on the railing around the judge's bench. With a piece of rope Horton then bound Murrell's hand to the railing. A negro brought a tinner's stove and placed it beside the sheriff. Horton took from the stove the branding iron, glanced at it, found it red hot, and put it on Murrell's thumb. The skin fried like meat. Horton held the iron on Murrell's hand until the smoke rose two feet. Then the iron was removed. Murrell stood the ordeal without flinching. When his hand was released he calmly tied a handkerchief around it and went back to the jail.'[12]

From Nashville Scene, "The Strange Story Behind the State's Thumb," by Betsy Phillips, 2015:

Once a year, the Tennessee State Museum takes out its strangest object... allegedly... the thumb of John Murrell, the great leader of the Mystic Clan, a kind of occult criminal organization that terrorized the people of Tennessee and Mississippi in the 1830s, while planning a vast slave insurrection that would give the Clan control of New Orleans and, perhaps, the whole Southeast. Said to be the son of a Methodist minister and a woman who ran a brothel while her husband was out riding the circuit, Murrell was bad from an early age. He often was said to have posed as a minister himself, preaching inside the church while his gang absconded with the congregation’s horses outside. Eventually... caught, tried for stealing a slave, and sentenced to ten years in prison, here in Nashville. After dying in prison, his body was cut up by curious medical students and, eventually, his thumb made its way to the State Museum, where it resides today. Almost none of this is true. Murrell was a horse thief and likely a slave-stealer. He did go to prison. He didn’t die in prison, though, so it’s likely both his thumbs are with the rest of his body, in a grave down by Chattanooga. There was no Mystic Clan. The truth is something stranger and more horrible. I can’t do it all justice here, because it’s just too weird and too complicated, but I highly recommend 'Flush Times & Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson' by Joshua D. Rothman... The short version is Virgil Stewart... a liar and a thief... In one somewhat failed effort to earn people’s respect, he hunted down John Murrell, a sickly, down-on-his-luck horse thief suspected of slave stealing and helped capture him... he hadn’t managed to track down the slaves Murrell was suspected of stealing, so people weren’t as impressed as he thought they should be. When he was called to testify against Murrell at the trial, he embellished the story somewhat, to make his deeds seem more heroic... Stewart then wrote a book under a pseudonym, in which he cast himself as the great hero in the daring capture of the great land pirate and head of the nefarious, wide-reaching Mystic Clan, John Murrell. Everyone in Tennessee, who had seen Murrell in real life, thought this was hilarious. Dude was ragtag, at best. He was no prince of the underworld. But in Mississippi, the white people were all “Oh, damn, did you hear about this Mystic Clan and their great plot to incite our slaves to murder us?” And then, the white people of Mississippi spent the summer of 1835 killing the [expletive] out of each other and innocent black people on the off-chance they were secretly members of the Mystic Clan. Like, you thought the Salem Witch Trials were bad? That’s nothing compared to the Mystic Clan “trials.” People were hanged left and right. People were whipped. People were run out of the state, shot, beat with rods. Counties went to war with each other. All while a “committee” “presided” over the “trials” and “executions” in order to make sure that no innocent people were killed. Everyone killed was innocent, of course, because there was no Mystic Clan... We tried to point out that Stewart was full of shit, but Mississippi was having none of it. After a while, it became apparent that there was no slave insurrection in the works, the committee disbanded, and everyone pretended like they’d just saved themselves from doom, through the extrajudicial murders of a bunch of people.[13]

From Ancestry, Rootsweb (TN Weakley), "Bushwackers, Gangs and Nightrider Stories Weakley County, Tennessee: 'John A. Murrell - Notorious Outlaw," compiled by Joe Stout:

From a typewritten paper kept with the Meridian Church books... Tradition says that John Murrell, the notorious horse thief 'preacher' and his band of thieving gangsters, paid old Meridian a visit in the early history of the Church... John A. Murrell was born in Middle Tennessee in 1804. His dad was a Methodist preacher, and he was gone a lot. John did not seem to respect his father, but rather his mother, who taught him and the other children to steal. She would hide from his father what they had stolen... Mark Twain wrote this about John Murrell. "When he traveled, his usual disguise was that of an itinerant preacher; and it is said that his discourses were very 'soul-moving'--interesting the hearers so much that they forgot to look after their horses, which were John A. Murrell was born in Middle Tennessee in 1804. His dad was a Methodist preacher, and he was gone a lot. John did not seem to respect his father, but rather his mother, who taught him and the other children to steal. She would hide from his father what they had stolen. Murrell's name first appeared in the court records of Williamson County in 1823 when he was fined fifty dollars for "riot," at which time three Murrells, one of which was the infamous John A., were bound in a sum of $200 to keep peace. Two years later he was in court for gaming. Later he was indicted for stealing a black mare from a widow in Williamson County. The case was taken to Davidson County on change of venue where he was convicted, flogged until he bled, branded on the thumbs, H T. In those days this branding indicated Horse Thief. He was sentenced to twelve months in prison. Later on, after moving to Jackson, Tennessee he formed a group of outlaws that he called the "clan." Denman Yocum, Esq, was a famous outlaw out west on the Chisholm trail. Squire Yocum was born in Kentucky around 1796. As a fourteen-year-old, he cut his criminal eyeteeth with his father and brothers in the infamous John A. Murrell gang who robbed travelers along the Natchez Trace in western Mississippi.'" [14]

From Ancestry, Rootsweb, G Bonnet, "Bonnet, Ayo, Bloomgarden, Yoast, and related families:"

John Andrews Murrell was a famous highwayman and bandit along the Natchez Trace. Historians differ as to which crimes Murrell was guilty of -- some believe he was a notorious murderer, others no more than a petty thief. However, several (unverified) family stories may be of interest. The story goes that Murrell, and three of his brothers (William, Jeffrey, and James) got their start in crime early, and under the tutelage of none other than their mother, Zilpha (Andrews) Murrell. She was the owner of a roadside inn, and trained her sons to sneak into patrons' rooms at night, loot their bags, and leave silently, and all of this was going on under the nose of her upright husband, Rev. Jeffrey Murrell, who was a Methodist minister. John A. Murrell's wife was Elizabeth Mangham, who was said to be a "woman of scarlet reputation." Given the moral climate of the time, that could mean almost anything, but the court records of Williamson County, Tennessee, do contain records of a charge that John's brother, Jeffrey Murrell, and Jeffrey's wife Mary "Polly" Staggs, were found guilty of keeping a brothel. John A. Murrell was captured in what is now the Kisatchie National Forest, Louisiana, and was brought back to Williamson County, Tennessee, where he stood trial for horse-stealing. Found guilty on May 25, 1826, he was given thirty lashes on his bare back, and had his thumb branded with an "H" (for horse thief). He was then put in jail for a year. Arrested a second time in 1834 on charges of slave stealing, Murrell was given a ten-year sentence in the state penitentiary. The prison record upon his incarceration reads as follows: "John A. Murrell was received in the Penintentiary August seventeenth one thousand eight hundred & thirty four he is five feet ten inches & a half in height & weighs from one hundred & fifty eight to one hundred & seventy pounds dark hair blue eyes long nose & much pitted with the smallpox tolerably fair complexion twenty eight years of age Born in Lunenburgh County Virginia & brought up in Williamson County Tennessee his mother wife and two children reside in the neighborhood of Denmark about nine miles from Jackson Madison county Tennessee his wife's maiden name was Mangham her connexion reside on the waters of South Harpeth Williamson Co. Tennessee. his Brother Wm. S. Murrell a Druggist resides in Cincinnatti Ohio he has another brother living in Sumpter County S. Carolina he has a scar on the middle joint of the finger next to the little finger of the left hand & one on the middle finger of the same hand a scar on the inside of the end of the finger next the little finger of the right hand has generally followed farming was found guilty of Negro stealing at the Circuit Court of Madison County & sentenced to Ten Years confinement in the jail & penitentiary House of the State of Tennessee.' (from the 1831-1842 Prison Record Book, Tennessee State Archives). When he was released (April 18, 1844), he was ill with tuberculosis and only lived another seven months. The Tennessee Democrat of November 23, 1844, states that on his deathbed, Murrell "acknowledged that he had been guilty of almost every crime charged against him, except murder... of this charge he declared himself 'guiltless.'" [sic] [15]

From Genealogy.com, Murrell: "Re: JOHN ANDREWS MURRELL 1806-1844, by Gayla Threatt:"

... John is my husband's 2nd Great Grandfather. My mother & I did some research on this family. LS Montoya also gave us the info below... He wasn't as bad as the press & others made him out to be, we don't think. On his death bed he said, he guessed he was guilty of most what was said, but not of murder... Jeffery was a minister but he was a Methodist. Jeffery moved to Middle Tennessee prior to Thomas, Sr. In 1805, he purchased 146 acres in Williamson County, a short distance from where Thomas would settle (in Dickson County) about a year later. His land adjoined that of another brother, Drury, and was near his father-in-law, Mark Andrews. Thomas' children all made respectable citizens, but Jeffery was not quite as fortunate. It is Jeffery's children that I call "Our Outlaw Cousins." Jeffery was an itinerant preacher and traveled throughout the countryside preaching the Gospel of Christ. His reputation was spotless, but his high moral standards were not shared by his wife, Zelphia Andrews Murrell, and their children. Before 1820, Jeffery and "Mom Murrell" (as Zelphia was sometimes called) owned an inn near Columbia, Tennessee. .. in his absence, she converted the inn into a brothel and a den of thieves. She taught her children to steal. After she made a traveler "so weary from the sport she had given him on his bed...that he probably would have slept through an earthquake," her son, John, or another child would pick the traveler's pockets... John A. Murrell, especially, was remarkable for his manly beauty, curling auburn hair, worn long generally, decorated a classic head, and a prepossessing face, that would, said an observer, have drawn attention and been noticed among a thousand people . . . His sister Leanna Murrell, was remarkable for her beauty, and was the most skillful dancer of her day." (Columbia Herald and Mail, June 8, 1877). Not only was John A. Murrell handsome, but he was well educated. He possessed a brilliant mind and was able to adapt to almost any environment. He used these assets to pursue a life of crime that is unparalleled in Southern History. He was our Outlaw Cousin. In his book, Life On the Mississippi, Mark Twain compared John Murrell to Jesse James: "Murel was his equal in boldness; in pluck; in rapacity; in cruelty, brutality, heartlessness, treachery, and in general and comprehensive vileness and shamelessness; and very much his superior in some larger aspects. James was a retail rascal; Murel, wholesale. James's modest genius dreamed of no loftier flight than the planning of raids upon cars, coaches, and country banks; Murel projected negro insurrections and the capture of New Orleans! And furthermore, on occasion, this Murel could go into a pulpit and edify the congregation. What are James and his half-dozen vulgar rascals compared with this stately old-time criminal, with his sermons, his meditated insurrections and city-captures, and his majestic following of ten hundred men, sworn to do his evil will!" (Mark Twain, Life On the Mississippi, pp. 205-206). John's mother taught him well. At the age of 16, he robbed the family treasury of fifty dollars and left home for Nashville. In Nashville, Murrell was recognized by one of his former victims from the Columbia inn. The man, however, was impressed by the young man's skill and asked Murrell to join him in a thieving adventure. This began his criminal career. Before he was 30, he was known as the great "Land Pirate" and was the most feared man along the Natchez Trace. Murrell was best known as a slave thief. By his own admission, he stole more than one hundred. Murrell's motto was, "Dead men tell no tales." Murrell loved fashionable clothes and beautiful horses. He was often seen in Nashville, Natchez, and New Orleans exquisitely dressed and riding fine horses. Usually, these possessions came from travelers he waylayed along the Natchez Trace.'" [sic] [16]

From "Dalton Newsletter - Dalton Gang Letter: September 1996," by Gordon Bonnet:

Jonathan Lyell and Mary Dalton had, among other children, Winifred Lyell, b. February 18, 1738 in North Farnham Parish, Richmond, Va. Winifred married Mark Andrews of Dinwiddie Co., Va., son of William Andrews and Avis Garnett, and had, among other children, a daughter named Zilphia Andrews. Winifred Lyell Andrews died in 1827. Zilphia Andrews married Jeffrey Murrell of Lunenburg Co., Va., son of William Murrell and Frances Pryor. They had, among other children, my ancestor, James H. Murrell, and the famous outlaw John A. Murrell... James H. Murrell moved to Louisiana, allegedly to escape his brother's bad name and influence, where he married on April 7, 1827, in Opelousas, La., to Mary Margaret McBride, daughter of Thomas Walter McBride and Julienne Bogard. They had, among other children, a daughter Emily Murrell, born on May 26, 1829 in Opelousas, La. Emily Murrell married in Opelousas on May 19, 1853 to Esprit Ariez Bonnet, son of Zacharie Bonnet and Marie Rebail of Gap, France. They had, among other children, Alfred Ariez Bonnet, who married Mary Emily Brandt, daughter of Wilhelm Brandt of Germany and Isabella Rulong. They were my paternal great-grandparents.[17]

From Ancestry, Rootsweb:

Zilpha Andrews was the wife of Jeffrey Murrell. Her father was Mark Andrews who arrived in Williamson County in 1801 from Virginia. Her mother was Winifred Lyell. Among the numerous brood of Mark Andrews was a daughter named Zilpha, a lady who does not always appear in family genealogies. She and Jeffrey had four daughters and four sons, among the m the legendy outlaw, John Murrell. Jeffery was already fifty-six years old when they married, closer in age to his father-in-law than his wife. Jeffrey died in 1824, leaving Zilpha to cope with mounting family problems. She was probably not forty yet. As long as she lived, the Murrells were gathered around her, including most of her sons when they were out of prison. She always provided support whenever a family member fell in difficulty. [18]

From the McMinville, Tennessee Gazette:

November 22, 1844 JOHN A. MURRELL, notorious land pirate, died Pikeville, Bledsoe Co., Tenn., Nov. 1, 1844; having admitted to many of his crimes but denied he had ever murdered anyone, as was announced in the McMinnville, Tennessee GAZETTE. MARRIAGE AND DEATH NOTICES, WEST TENNESSEE WHIG. OCT, 1842 - JUNE 1867, JACKSON, MADISON COUNTY TENNESSEE : 'Died in Pikeville, Bledsoe county, on Sunday the 1st inst., of pulmonary consumption, JOHN A MURRELL, the notorious land pirate.[19]

Sources

- ↑ Life on the Mississippi, [a fictionalized account] by Mark Twain (Harper, 1883) p. 243 Life on the Mississippi

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Arkansas, "John Andrews Murrell (1806–1844)" Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- ↑ Notes From Under Grounds, by David Whitesell (Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections 'Small Notes' blog, University of Virginia, Nov. 2014)Notes From Under Grounds

- ↑ Wikipedia: "John Murrell (bandit)"John Murrell (bandit)

- ↑ James Phelan, History of Tennessee: The Making of a State, (Houghton, Mifflin, Chapter XXXII) pp. 343, 347 History of Tennessee

- ↑ Robert E. Howard, Two Gun Raconteur, "The Hellbender, John A. Murrell," by Keith Taylor The Hellbender, John A. Murrell

- ↑ Ancestry: Rootsweb; Obion County, TN GenWeb; (LGMathis) 'Obion Co TN Branches & Twigs - Obion Co., Tn Family Branches Rootsweb, citing Nashville American

- ↑ Flush Times & Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson, by Joshua D. Rothman (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2012)Flush Times & Fever Dreams

- ↑ Journals: The Author 2016: Review of Flush Times & Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson, by Joshua D. Rothman (Oxford University Press) Review of Fever Dreams

- ↑ Daily Beast: "Django Unchained’s Bloody Real History in Mississippi," by Adam Rothman, 2013 Daily Beast

- ↑ Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama, 1800-1840 (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, date) p. 234 Murrell, Stewart

- ↑ Ancestry: Fold 3, "John Murrell and the 1835 slave revolt;" citing Grimstead, 1998: 320-21 Fold 3

- ↑ Nashville Scene, "The Strange Story Behind the State's Thumb," by Betsy Phillips, 2015.Nashville Scene

- ↑ Ancestry, Rootsweb (TN Weakley), :Bushwackers, Gangs and Nightrider Stories Weakley County, Tennessee: John A. Murrell - Notorious Outlaw," compiled by Joe Stout from various sources. [1]

- ↑ Ancestry, Rootsweb, G Bonnet, "Bonnet, Ayo, Bloomgarden, Yoast, and related families" G Bonnet

- ↑ Genealogy.com, Murrell: "Re: JOHN ANDREWS MURRELL 1806-1844, by Gayla Threatt"by Gayla Threatt

- ↑ "Dalton Newsletter - Dalton Newsletter: September 1996," by Gordon Bonnet Dalton Newsletter, citing Southwest Louisiana Records, by Father Donald J. Hebert; (Hebert Publications: Rayne, LA, 1974 - 1990)

- ↑ Ancestry, Rootsweb page Rootsweb page

- ↑ McMinville, Tennessee Gazette, Friday, Nov. 22, 1844.

See Also:

- Wikidata: Item Q2403455

- "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, UT: Personal Ancestral File - Robert Anthony Perry.'" [2]

- "Rare Newspapers: 'Death of John Murrell... famous land pirate' Nov 29, 1844." [3]

- "Find A Grave: 'John Andrews Murrell... Son of Rev. Jeffrey Gilliam Murrell, Jr. (1738 Lunenburg, VA - 11/25/1824 Williamson County, TN).'" This memorial has been deleted.

- Ross Phares, Reverend Devil: Master Criminal of the Old South, (Pelican, 1974) John Murrell

- James L. Penick, The Great Western Land Pirate: John Murrell in Legend and History (University of Missouri Press, 1981)

- HR Howard, The life and adventures of John A. Murrell, the great western land pirate, with twenty-one spirited illustrative engravings (New York: H. Long & Brother, 1847) great western land pirate

- "'Wicked River: The Mississippi When It Last Ran Wild' by Lee Sandlin; Pantheon. [4]

- "Genealogyl Trails: 'MADISON COUNTY TENNESSEE; THE 'MURRELL GANG' - John A. Murrell & Daniel Crenshaw West Tennessee's Local Bandits.'" [5]

- "Madison County, Tennessee: Historical Sketches of the County and Its People, by M. Secrist; Lulu Press, 2013." [6]

- "The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume 1; Volume 7, by Junius P. Rodriguez ABC-CLIO." [7]

- "Huntsville History Collection: 'Natchez Trace Bandits: John A. Murrell, A Vintage Vignette', by John P. Rankin, 2011: '[8]

- "The Great Western Land Pirate, Again: An Essay Occasioned by a Diary Entry of Private Tabler', by William Edward Henry" [9]

- "DataB.US: 'John Murrell (bandit)'. [10]

- "'American Pirates: Jean Lafitte, Edward Low, William Walker, John Ashley, Raphael Semmes, John Ordronaux, John Murrell, Pierre Lafitte, Thomas Tew', et al; Wikipedia University-Press, 2013.'" [11]

- "Wikipedia: 'John A. Murrell Grave 'John A. Murrell Grave photograph." [12]

- "Ancestry: Rootsweb; Perry - Webb Families in Tennessee/Kentucky Source: THE ANDREWS FAMILY OF VIRGINIA, TENNESSEE, MISSOURI, AND BEYOND, by Grace Andrews Maglione 1990 776 Seven Hills Lane, St. Charles, MO63303 Page 9-10.

- Source for information on Murrell Family is from Ellender Murrell Boudreaux of Louisiana.

No known carriers of John's ancestors' DNA have taken a DNA test. Have you taken a test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

- Notable vs. Notorious Jul 31, 2016.

Featured Eurovision connections: John is 30 degrees from Agnetha Fältskog, 24 degrees from Anni-Frid Synni Reuß, 25 degrees from Corry Brokken, 17 degrees from Céline Dion, 26 degrees from Françoise Dorin, 27 degrees from France Gall, 28 degrees from Lulu Kennedy-Cairns, 23 degrees from Lill-Babs Svensson, 18 degrees from Olivia Newton-John, 33 degrees from Henriette Nanette Paërl, 31 degrees from Annie Schmidt and 18 degrees from Moira Kennedy on our single family tree. Login to see how you relate to 33 million family members.

M > Murrell > John Andrews Murrell

Categories: Gangsters | Lunenburg County, Virginia | Unknown County, Mississippi | Opelousas, Louisiana | American Outlaws | Notables