| Jacques (de Savoye) de Savoije is a Cape of Good Hope - Kaap de Goede Hoop (1652-1806) Stamouer-Progenitor Join: Cape of Good Hope - Kaap de Goede Hoop (1652-1806) Project Discuss: DUTCH_CAPE_COLONY_PROGENITORS |

Contents |

Biography

Name

Birth

- Date: Jacques was born about 1636 [6] / in 1636. [1][2][4][5][7][3]

- Place: Aeth, France [4][6] / Aeth, Hainault, [Belgium] [3] / Walloon Region, [Belgium] [7] / Henegouwe in Spaanse Nederland [1] / Aeth, Hainant, France [2] / Ath, Hainaut, [Belgium] [5]

Baptism

Event

Name mentioned

- Today baptism ('1701) at the Groote Kerk, Cape Town of Christina de Veij / Vijf' daughter of exiled (later pardoned) Chinese convict LIM Inko aka Abraham de Veij / de Vijf & freed slave Maria Jacobs (from Batavia) baptized Cape of Good Hope (Namen der Christen Kinderen) 18 December 1701 (father: Inko de Chinees) (mother: Maria {Jacobs} van Batavia) (witnesses: Maria de Savoije, Maria–Magdalene le Clercq, 2nd wife of Jacques de Savoye (from Ath in Hainault [Belgium])] & Pieter Meijer); she signs her name "Christina de Vijf"... [9]

Migration

Death

- Date: Jacques de Savoye passed away about 1695 [4] / [in] [1][6] / [on] 8 Oct, 1717 [2][3][5][7]

- Place: Kaapstad [2] / Drakenstein, [South Africa] [3][7] / [Cape Town] Western Cape [South Africa] [5]

Events

English

- Between 1690 and 1724, 54 Huguenots signed documents. These signatures were published by Graham Botha in his book The French Refugees at the Cape and includes those of Louis de Berault, Pierre Simond, Jacques Delporte, Jean Durand, Jacques de Savoye, Jacques Nourtier, André Gauch, François Retif, Guillaume Néel, Paul Roux, Daniel Hùgo, David Senecal, Jean Prieur du Plessis, Guillaume du Toit, François du Toit, Jean le Roux (or Jean le Roux de Normandie?), Jacques Therond, Hercules des Prez, Abraham de Villiers, Jean Gardiol, Jacques de Villiers, Pierre de Villiers, Isaac Taillefert (or Isaac Taillefer-164)), Jean Taillefert, Jean Gardé, Claude Marais, Estienne Bruére, Daniel des Ruelles, Pierre Rousseau, Jacques Pinard, Estienne Cronje, Jacques Malan, Gabriel le Roux, David du Buisson, Daniel Nourtier, Estienne Niel, Philippe Fouché, Gideon le Grand, Pierre Cronjé, Paul Couvret, Paul le Febvre, Salomon de Gournay, Pierre Vivier, Pierre Jourdan, Estienne Viret, Esaias Engelbert Caucheteux and Jean de Buijs. [10] These signatures were almost certainly also some of those of the 240 burghers who signed the petition headed by Adam Tas [11] against corruption and cronyism by the Government of Willem Adriaan van der stel. [12]

- 1688 - 1702 JACQUES DE SAVOYE AND MARIE-MADELEINE LE CLERCQ [13]

- The story of' Vrede & Lust starts in 1686. In Flanders, 50-year-old Jacques de Savoye is being persecuted by religious fanatics, he has just lost the wife who endured labour nine times to provide him with heirs, and his textile trading business in Ghent is ruined. [13][14]

- De Savoye relocates to nearby Middelburg in Zealand and when the widower meets and marries 26-year-old Marie-Madeleine le Clercq, life is looking up. The newlyweds decide to make a clean break when the opportunity arises to join the exodus to the Cape. Ever since the Jesuit assassination attempt in retaliation against De Savoye’s hosting of Reformed services in his home, he has felt as threatened as the French Huguenots. [13]

- The travelling party includes De Savoye’s mother-in-law, Anthonette Carnoij, two children from his first marriage, Margo (17) and Barbère (15), the new baby, Jacques (9 months), plus three servants, the Nortier brothers, Jean, Jacob and Daniel. The latter, a carpenter, will be accompanied by his wife, Maria Vijtou. To smooth his way in the new country, De Savoye sets about obtaining letters of commendation, which refer to De Savoye as well as his servants as eminent people: “his [De Savoye’s] life seemed a worthy example of purity and holiness, in an environment where idolatry reigned supreme and such a lifestyle was almost impossible”. [13]

- The 160-foot Oosterlandt [15][16] captained by Carel van Marseveen, departs from Middelburg on January 29, 1688. Amongst the European passengers are the families of Jean Prieur du Plessis and Isaac Taillefert and the soldier Jacques Therond. After 70 days, the immigrants arrive in Table Bay on April 26, a fine day. Instead of having to divert to Saldanha, the Oosterland anchors and the passengers are ferried ashore by rowing boat. [13]

- Their first impressions of the awesome mountain are counterbalanced by the diminutive size of the settlement. They have arrived on a new continent, to start a new life. Some will adapt and survive, others not. Madeleine du Plessis will last five years before returning to Europe. The Tailleferts will lose two children within the year. In De Savoye family records, there is mention of a second child, Jacquette, but because one does not read about her in later documents, she may have been born at sea and died during the southbound journey. Undeterred, the resolute Savoyes, as can be predicted from their colourful past, now embark on a most wondrous adventure. [13]

- A farm in Africa

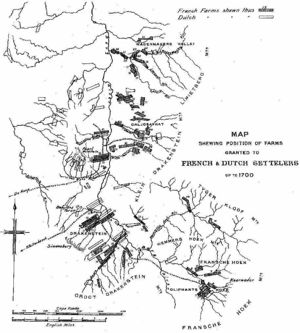

- The scene shifts to Drakenstein, the furthest outpost of the Cape colony, still sparsely populated with only 23 Dutch freeburghers having settled there the year before. The valley is majestically beautiful, though quite rugged, with dense forests, game, notably lion and tiger, and nomadic Khoi (Hottentot). The pioneers live in simple clay and reed homes. [13]

- Nothing in De Savoye’s earlier career suggests that agricultural pursuits such as ploughing, planting, building and raising livestock would attract the merchant, but he now becomes the owner of a magnificent piece of property against the foothills of the Napoleonsberg (today known as Simonsberg). He calls his farm Vrede en Lust (Peace and Delight), nurturing visions of a rural paradise where he can spend his last days. Although the land becomes his full and free property with immediate effect, he only receives the title deed to the 120 morgen[17] six years later, on 15 April 1694. It is then signed and issued by Simon van der Stel, Council Extraordinary of India and Governor of the United Netherlands Chartered East India Company at the Cape of Good Hope,[18] on condition that De Savoye regularly replace trees felled on his farm with young oak trees or other afforestation, and supply the Honourable Company with one tenth of his annual wheatcrop.[19] As a novice farmer, De Savoye prospers, unlike most of the Huguenots, who complain so much about stony and marshy soil that they qualify for handouts from Batavia. Even though he runs up far more debt for initial supplies than any of the other newcomers, he makes a concerted effort to pay back his dues. In 1688 he owes 783 florins, the following year only 144 florins. [13]

- “We Simon van der Stel, Councillor Extraordinary of India, Governor under the United Netherlands Chartered East Indies Company at the Cape of Good Hope, the Island Mauritius and the territory thereabouts, and We, the Councillors, herewith make known [13]

- “That in the year 1688 was granted, ceded and given to the Free Agriculturist and Heemraad Jacobus de Savoye in full and free ownership and is granted, ceded and given to him by these, certain piece of land named Vrede en Lust, situated in Drakestein, extending W.S.W. upwards to the Simonsberg and E.N.E. downwards to the properties of Roelof van Wijk and Hendrik Eekhof, S.S.E. to that of Charl Mare and N.N.W. to that of Daniel Noodje, measuring in length AB and CD six hundred, in breadth AD and BC one hundred and twenty roods, altogether in extent measuring 120 morgen Rhineland measure as indicated by the above figure ABCD by the Surveyor; with full power and authority to plow, sow, cultivate, afforestate, to possess in full ownership, to administer and thereafter should he so desire to sell the said land, to hire it out or to alienate it in any manner whatsoever, in accordance with such laws as may be in force in this Government; and he shall continue to be responsible for and to construct beside his cornfields, a common wagon road for the use and convenience of himself as well as for the other settlers; and also a ford across the river the same width as the road; and further he shall be responsible to replace from time to time the trees chopped down on his farm with young oaks or other timber; and over and above all this, he shall be liable to bring in yearly to the Governor of the Honourable Company a tithe of his grain crop, under penalty that should he fail to carry out promptly these conditions, or should he not plant and cultivate the land in accordance with the laws proclaimed, the authorities shall be free to take the said land from him for the benefit of and to remain under the control of the Government; and he shall be liable to such taxes and perform such public duties as are laid down by the Government here, or as may be imposed in the future for the benefit of the Honourable Company and for the welfare of the Colony.

- Thus granted and given in the Castle of Good Hope

- 15 April Anno 1694 S. v.d. Stel

- SEAL

- By Order of the Hon. Governor and Councillors J.G. De Grevenbroek. Secretary. [13]

- De Savoye contributes greatly to the development of the Drakenstein valley. On 4 January 1689 he is elected Heemraad (Magistrate) because of his efficiency and knowledge of the Dutch and French languages, as well as his comprehension of the Portuguese spoken in the Indies. Van der Stel writes to the Delft Chamber, saying that De Savoye and family are an example for all the refugees and exiles. On 28 November 1689 De Savoye, together with the Reverend Pierre Simond and three other Huguenots, requests that the French farms be spaced closer together so that a church council can be nominated. Two thirds of the community are unable to follow a Dutch sermon, and living one, two or even three hours on horseback from each other, the new farmers struggle to learn the Dutch language. Despite Van der Stel’s indignation, the request is forwarded to the Netherlands and the Here XVII of the Dutch East India Company comply. Two years later De Savoye finally becomes a member of the first French church council comprising four elders and five deacons. By 1692 De Savoye is running a successful mixed farming enterprise. Bar one, he produces the most wheat and barley of all the burghers. He owns four horses, 30 cattle, 10 000 vines and slaves such as Jan from Madagascar and Maria of Bengal. Carpenter Barent Jansz is engaged to build a proper house and when the two men later become involved in a dispute regarding remuneration, the Magistrate determines that De Savoye actually paid too much! [13]

- Meanwhile, the Nortier brothers are doing extremely well for themselves, considering that most young men who came to the Cape were soldiers and sailors and, if they were lucky, farmhands. Daniel, the carpenter, is making money in his spare time doing woodwork. Soon he is ready to claim independence for him and his young family. He and Marie lost their first-born, Jacques, born shortly after their arrival, but a mere two years after arriving in the Drakenstein valley, Nortier becomes the brand new owner of the neighbouring farm La Motte. His brother, Jean, acquires the deed of grant to the adjacent farm Fredericksburg. [13]

- The De Savoyes find it easy to adjust to the predominantly Dutch society at the Cape. Jacques is soon known to all as Jacobus, and the lady of the house, Marie-Madeleine, becomes Maria Magdalena. For Maria one feels a fair amount of admiration. She seems to be adapting well to her new circumstances, so far removed from European culture in every conceivable way, but she is astute and no stranger to hard work. Maria is in fact so capable that she holds power of attorney for Jacobus when in the Cape. For all intents and purposes, she is an active business partner, a no-nonsense type of woman, blessed with a lot of common sense, like her mother, who was destitute but emancipated. In The Hague, Anthonette Carnoij was often at the mercy of charity from the Walloon Church, but in the Cape she confidently engages in dealings with her church in Holland. [13]

- The well-known De Savoyes are held in high esteem. When little Aletta is born a year after their arrival in the colony, Simon van der Stel acts as witness to the christening in Cape Town on 17 July 1689. Not long afterwards Jacobus’ eldest daughter, Margo (in her will, she writes her name as Margarita Theresia de Savoy) who married Christoffel Snyman, also spelt Cristoffle Cnayman, Senayment, Sceniemen, Seniman or Snijman, not long after the family’s arrival in the Cape, gives birth to the infant Catharina. Christoffel is the son of a free black called Antony from Bengal and Catharina of Palicatte. Far from the scandal one would imagine, interracial marriages between whites and freed slaves were not uncommon at the Cape and in the Stellenbosch and Drakenstein districts. For a man like Christoffel it was not unusual to integrate with the local community, both socially and economically. Nothing prevented him from owning a farm, as did Jonkershoek landholders Anthonie from Angola, Louis from Bengal and Jan from Ceylon. Church controversy De Savoye is a man of contrasts. He has a fiery temper and is quick to take offence, but is willing to share prosperity, as proven by his support of the Nortier brothers’ attempt at gaining their independence. [13]

- Unfortunately, a number of incidents cloud De Savoye’s reputation in a small community that thrives on malicious gossip. Rumours that such a well-known and respected citizen as himself has been declared bankrupt in the Netherlands hurt him deeply, and although they are not unfounded, De Savoye feels that he has to clear his name. The Reverend Pierre Simond, for whom the hamlet Simondium was named, takes his position as shepherd very seriously and places De Savoye under censure. A bitter argument ensues and De Savoye is refused communion. Each of the two men has his supporters, thereby creating a rift in the tightly-knit community of Drakenstein. De Savoye approaches the Stellenbosch parish for membership and is accepted. In the interim, he writes to the Netherlands, accusing Simond of various wrongs, such as the intention of importing an oven which everyone else will be forced to use for baking bread, and the fact that Simond’s wife is selling all sorts of things! Moreover, he is upset that Simond demands one tenth of the parish income and opposes a church council so that he can rule like a pope or a bishop. Simond denies everything and in support of their minister, forty-eight of the French testify that they have nothing but praise for him and that the accusations are mere libel. The plot thickens when Christoffel Snyman, presents his baby for the christening with his father-in-law, De Savoye, as witness. Simond declares, in front of the entire congregation, that he will christen the child but cannot accept De Savoye. [13]

- De Savoye, his wife and daughter then launch a vociferous attack in front of the pulpit. Not only do they insult Simond, they threaten to expel him into everlasting perdition. He is called a “tartufle” (hypocrite), a priest, a Jesuit, a Judas, a “caffre” (infidel), a false shepherd, and they promise that their influential friends will teach “ce beau petit Monsieur” (this pretty little chap) a lesson! Simond retaliates in the form of 37 written pages, in which he shows himself to be a master of rhetoric! The council nevertheless investigates Simond’s affairs and in retrospect, this was a spurious attack on officialdom. The combined church councils of the Cape, Stellenbosch and Drakenstein conclude that Simond should have accommodated De Savoye in his church and that the brothers should reconcile, expressing their dismay at the unforgiving nature of the French Calvinists who cannot control their disputes. In essence De Savoye remains a querulous character. He has a habit of becoming embroiled in court cases, often over mere trifles. On 26 February 1693 he takes Pieter Beuk to court over a handsaw. Shortly afterwards, it is Pieter Meyer’s turn to take his employer to court for not paying his wages in full. In 1694, Coert Helm and Daniel Bouvat sue him for the same reason. Several other court cases are noted, such as the maintenance of a drift, De Savoye being responsible for the upkeep of the road between his farm and Klapmuts. Governor Van der Stel even receives a letter from the Rotterdam Chamber concerning De Savoye’s crotchety temper. It reads: “[…] his nature can only be effectively altered and improved by time, kind intercourse, and treatment. This we readily entrust to your discretion.” [13]

- Ironically, the first Huguenot church, little more than a barn, was probably located on land belonging to De Savoye, since the address of the church is “The French Huguenot Parish, Vredeen- Lust, Simonsberg”. One of the most impassioned advocates for the erection of a church, De Savoye acquires an annex of 60 morgen to the south of his farm and north of the Grootrivier, on 22 December 1694. Of this, 48 morgen are allocated to the Drakenstein parish. This eastern part of the annex is now known as Rust-en-Vrede and forms part of Plaisir de Merle. [13]

- In 1695, De Savoye is elected one of the first officers when Stellenbosch establishes its own burgher military force and, his status reaffirmed, he proudly leads the company of foot soldiers. As a captain in the Drakenstein Infantry, serving until 1700, De Savoye attends annual military manoeuvres which include drilling and shooting at targets with flint-lock muskets loaded with loose powder. These manoeuvers are a popular social event with the burghers. [13]

- That same year, a signal canon is erected on Simonsberg to tie in with the signalling system at Cabo, defence having become an important matter to the far-off community. When rumours suggest that the French may attack the Cape, the burgher unit, consisting of 100 inhabitants of Stellenbosch and Drakenstein, perform active duty every 14 days, reinforcing the Cape garrison on a relay base. In future they would be called up on a regular basis for duty at the Cape and in the interior, for example in 1715, when commando’s were mounted against the San who stole cattle. [13]

- Family matters

- The family’s living conditions probably consist of a tiny, flat-roofed structure. In all likelihood, the church building is probably De Savoye’s first attempt at building a house, since it is described as the “hut of one of our Frenchmen who has moved” (loge d’un de nos français qui a changé de place”). The traveller Valentyn describes it as a small, low building with walls not higher than three or four feet, made of clay with a flat thatch roof. [20] The first houses were all rudimentary, built with the most basic implements and dependent on the natural materials that are available – a mixture of clay and reeds, the bricks moulded roughly, dried in the sun and cemented with burnt limestone. Free burghers who did not find clay often built ‘hardbieshuise’, believed to be named after the hard reeds or ‘biesies’ used to build them. These huts were similar to the grass huts of the blacks further north, although larger and more commodious. Building homes took second place to establishing crops and livestock herds that would enable the burghers to repay the company for their land.[21][13]

- As early as 1658, fuel for the firing kilns had become so scarce at the Cape that the search for wood had extended to the settlements of the free burghers. The Company then prohibited the brick and lime makers from collecting the small bushes growing on the Cape flats, as the settlers used to for plaiting the walls of their huts. Meanwhile, Jacques and Maria are blessed with another child. Little Aletta is five when her brother is born. Philippe Rodolphe (spelt Rodolf in Dutch) is the first baby to be christened in the new Drakenstein church, according to the entry in the register, which dates from August 1694. With Jacques attending to judicial, religious and military matters, it is Maria who holds the fort, not only inside her little clay house, but also on the surrounding land, with the help of servants, mostly soldiers granted as contract workers. Two sons-in-law, Pieter Meyer and Christian Ehlers, are also occasional employees of the family. For the sake of his two sons, De Savoye acquires two more farms: in 1698, one at Simonsvlei, and soon thereafter the farm Kromme Rivier in Wagenmaker’s Valley, to the north of the current Wellington. In 1705, he purchases another farm in this vicinity. He applies for permission to hunt, like many farmers who thus provide for their families, and permission is granted to shoot eland and hartebees in the vicinity of Roodesand. The land is leased to other farmers, the first being Lanquedoc’s Jacques Therond, the soldier who was also on board the Oosterland when they first journeyed to the Cape, on condition that he build a house and kraal and plant 5 000 vines. De Savoye retains a third interest in the farm and never gains much profit from its operations. [13]

- Although he appears to flourish, the opposite is true. His finances at the Cape have become just as precarious as they were in Europe. The turn of the century is not a very joyous occasion on Vrede en Lust. The inhabitants are no longer optimistic, merely stoic. The southernmost tip of Africa brought opportunity for De Savoye and his family, but life is difficult – in fact, it is one long struggle for survival. So much remains to be done, so much wilderness to be tamed. At heart De Savoye is a European gentleman, an entrepreneur, a businessman, not a farmer. It will take another century, and many more hardworking men, born to the land, before the farm is sufficiently developed to claim its rightful place amongst the thriving Cape wine estates. [13]

- Barely a year into the new century, De Savoye gives up full scale farming. By 1701, the Company, to whom De Savoye is heavily indebted, insists on repayment of the loan. He raises some cash by selling Vrede en Lust to his son-in-law, Christiaan Ehlers, and accepts a mortgage bond for the balance of the sale price. This bond is immediately transferred to his old enemy Pierre Simond, possibly to cancel the debt for the house in Table Valley, on the corner of the present-day Burg and Castle Streets, which De Savoye buys when the 50-year-old Simond returns to Europe. [13]

- At Cabo, De Savoye engages in a commercial venture dealing in agricultural produce, but fails to meet with great success. He buys skins and makes pants for sailors to earn extra pocket. Aged 70, having lost none of his fighting spirit, De Savoye also attempts to expose the corrupt government of Governor Willem Adriaen van der Stel and becomes a leading champion of the burgher cause. He is arrested in 1706, together with two of his sons-in-law, namely Pierre Meyer of Dauphine (Aletta’s husband) and Elias Kina (Barbe-Thérèse’s second husband). The dissidents are imprisoned in the infamous ‘Dark Hole’ in the Castle, which Adam Tas, the wellknown diarist, describes as the most putrid prison in the world, where usually only prisoners condemned to death spent their last days. When Pieter Meyer becomes ill, he relents in a diplomatically worded statement, saying that he regrets all his wrongdoings, but De Savoye shows no fear and says he signed the petition because the Cape was going to the dogs. His only goal, he insists, is to prevent officials from owning property and allow the burghers free trade in cattle, grain and wine. [13]

- On 12 February 1712 De Savoye applies for free passage back to the United Provinces[22] for him, his wife and mother-in-law. This is not granted, but in view of their age and indigence, they pay half-fare as deck passengers on Cornelis de Geus’s ship the Samson. Why does De Savoye not ask for assistance from his three sons-in-law? Is he too proud, or are relations strained? The house in Table Valley is only sold in April 1713, the year of the small-pox epidemic, which means that those proceeds could not be used either. [13]

- When De Savoye and his wife are admitted to membership of the Walloon Church in Amsterdam in 1714, with a Cape attestation, there is no mention of Anthonette Carnoij. She may have passed away in the course of the journey. Yet another major and unforeseen upheaval awaits the family. The next year, the couple’s son, Philippe Rodolphe, who had been sent to Europe as a young man for his education, returns to the Cape, taking passage on the Westerdijxhom as a soldier and subsequently joining the shore establishment, where he rises to the rank of junior merchant. [13]

- With three daughters and numerous grandchildren also in the colony, the parents are induced to leave Holland once again and make the long journey back to the Cape, where they are admitted as members of the congregation on 16 March 1716. On 15 September of that year, Jacobus de Savoyen presents his son, then aged 22, for church membership. Philippe Rodolphe leads a respectable life as book-keeper and military paymaster, a member of the Orphan Board and the Marriage Board, a Cape deacon and cellar master of the East India Company in Cape Town. He is appointed to the latter position in 1721 and still occupies it at the time of his death in 1741, when the surname De Savoye dies out in South Africa. [13]

- Jacques, the baby who accompanied his parents on their long south-bound voyage, never farms near Simonsvlei. The farm on the Kromme River was promised to his mother by Simon van der Stel in 1689 and held in trust for the minor, together with another property in the region, but his early death occurs some time before 1708. Margo becomes the founding mother of the Snymans in South Africa. The couple have nine children before Christoffel passed away and in 1707, the 36-year-old widow marries Henning Viljoen. The following year, her eldest, Catharina, marries Johannes Viljoen, the brother of her stepfather. The descendants of both Henning Viljoen and Johannes Viljoen are therefore also descendants of Jacobus de Savoye. Aletta, the first of the De Savoye children to be born on African soil, marries Pierre (Pieter) Meyer, a Huguenot from Dauphine, one of the original immigrants in 1688. One of Aletta’s sons, Philippe Rudolph Meyer, becomes deputy-merchant and cellar master of the Cape government. The Meyers have seven children and countless Meyers are also direct descendants of Jacques de Savoye. [13]

- Two years after his return to Africa, in October 1717, Jacques de Savoye passes away – aged 81 and a pauper. His wife, Maria Magdalena, dies in May 1721. Vrede en Lust’s first owner was a man of great vision, a megalomaniac, whose great strength lay in his powerful religious life and voluntary efforts as a missionary for the Protestant cause. [13][23]

- De Savoye, Jacques, (*Ath, Bel., 1636 - †Cape, October, 1717), merchant and Cape free burgher, was the son of Jacques de Savoye and his wife, Jeanne van der Zee (Delamere, Desuslamer). De S. was a wealthy merchant in Ghent, Belgium, but his devotion to the Protestant religion led to his persecution by the Jesuits, and there was even an attempt to murder him. [24] In 1687 he moved to the Netherlands and left for the Cape in the Oosterland on 29.1.1688. In addition to his wife, mother-in-law and three of his children, he was accompanied by the brothers Jean, Jacob and Daniel Nourtier. [7]

- Came to the Cape in 1688 aboard the "Oosterland." Farmed "Vrede-en-Lust" near Simondium from 1688 to 1702 when it was sold. The family moved to Cape Town where Jacques started a Commercial enterprise in 1702 and then sold in 1708. He was the District Councillor for Stellenbosch and Drakenstein. He was arrested in 1706 for opposition to the Governor W.A. van der Stel and subsequently released. [7]

- De S. soon became a leader among the French community at the Cape: he was one of the deputation which, on 28.11.1689, asked the Governor and Council of Policy for a separate congregation for the French refugees, and the following year he helped to administer the funds donated to the French refugees by the charity board of the church of Batavia. At various times he also served on the college of landdros and heemraden. [7]

- To begin with, De S. farmed at Vrede-en-Lust at Simondium and in 1699 was also given Leeuwenvallei in the Wagenmakersvallei (Wellington), but settled at the Cape soon afterwards. He apparently experienced financial difficulties since in 1701 he owed the Cape church council 816 guilders and various people sued him for outstanding debts. In 1712 he described himself as being without means. [7]

- In March 1712 he left for the Netherlands in the Samson, accompanied by his wife and mother-in-law. He enrolled as a member of the Walloon congregation in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, on 16.12.1714, but only four months later, on 20.4.1715, it was reported that he had returned to the Cape. There is, however no documentary proof of his presence at the Cape after 1715, nor of C.G. Botha's assertion that he died in October 1717. [7]

- De S. often clashed with other people. During the struggle of the free burghers against Wilhem Adriaen van der Stel, he was strongly opposed to the Governor and was imprisoned in the Castle for a time. He was also involved in a long-drawn-out dispute with the Rev. Pierre Simond,* and he and Hercules des Pré went to court on several occasions to settle their differences. [7]

- He was married twice: first to Christiana du Pont and then to Marie Madeleine le Clercq of Tournai, Belgium, daughter of Philippe le Clercq and his wife, Antoinette Carnoy. Five children were born of the first marriage and three of the second. Three married daughters and a son remained behind at the Cape, as well as a son who was a junior merchant in the service of the V.O.C. and who died without leaving an heir.[25][7]

- Most probably, Jacques' first wife Christine du Pont, died in Kent, before he and his daughter Magatha (as she referred to herself), came to the Cape according to certain sources. Other sources refer to a marriage with le Clerq on more or less the same date of his first wife's death. This was before 1686. Jacques left for the Cape on the Oosterland. Some sources indicate that he and his daughter Margatha made that trip. (and not his second wife). Margatha was not the daughter of the wife (le Clerq) There are some discrepancy to sort out, that may be possible to resolve by making use of fixed dates. As far as I am concerned, the marriage ended due to the death of Christine. [5]

Afrikaans

- De Savoye, Jacques

- Hy was 'n handelaar in Ghent. [7] Hy was eers getroud met Christiana du Pont op 4 Jul 1657 in Frankryk. [7]

- Vlug 1667 na Franse verowering van Ath na Gent in Vlaandere; uitgesproke Calvinis; verhuis 1686 as wewenaar na Sas van Gent in Zeeland. In 1687 gaan hy en gesin na Middelburg, Zeeland, en in 1688 op die skip Oosterland na die Kaap. [7]

- Jacques, Madeleine (sy tweede vrou) en sy familie is op 'n passasierslys van die "Oosterland" wat heelwat vlugtelinge na die Kaap gebring het in 1688. Hulle was ongeveer 1686 in Gent getroud, en arriveer in die Kaap as Franse Hugenote in 1688, saam met Jacques se 2 dogters uit sy eerste huwelik met Christiana du Pont, nl. Margaretha Theresa (17) en Barbere Theresa (15) asook Antoinette Carnoy en die baba seuntjie Jacques. [7]

- About Jacques Dureau

- "Beste Loffie, M Boucher het van die inligting, oor die ouers van Jacques de Savoye, uit die SA Biografiese Woordeboek gebruik gemaak vir sy boek French Speakers at the Cape: the European background.

- Ek het in 1993 van 'n genealoog in België se dienste gebruik gemaak wat deur die Katolieke Doopregister 1582 - 1796; die Katolieke Huweliksregister 1616 - 1796 van Ath, België asook deur die "Civil Records" van Ath 1582 - 1795 en 1652 - 1674 gewerk het. Jacques de Savoye is op 29 Januarie 1636 gedoop en nie gebore nie. Hy was die tweede kind van Julien de Savoye, gedoop Ath 26 Oktober 1602 en Jeanne Dureau/Durieau

- Julien de Savoye was die sesde kind van Jacques de Savoye en Jeanne van der Zee/da la Mere -Jeanne Dureau was 'n dogter van Jacques Dureau/Durieau en Marie Ghersouille.

- Ek weet nie of die De Savoyes Rooms Katolieke of Protestante was nie. Jacques de Savoye was 'n Protestant toe hy en sy gesin hulle aan die Kaap kom vestig het. Hy was een van die afvaardiging van 5 Hugenote wat op 28 November 1689 onder leiding van Pierre Simond vir goewerneur Simon van der Stel besoek het om 'n eie gemeente en kerkraad vir die Hugenote te versoek.

- Vriendelike groete, Juna Malherbe, Franschhoek" [23]

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 WikiTree profile De Savoye-15 created by Pieter Meyer, Apr 9, 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 WikiTree profile De Savoye-10 created through the import of wikitree upload.ged on Jul 19, 2012 by Arrie Klopper.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 WikiTree profile De Savoye-13 created through the import of Ancestors_DippenaarAndre_noinfo.GED on Oct 23, 2012 by Andrew Dippenaar.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 WikiTree profile De Savoye-32 created by Schalk Pienaar, Jul 14 2014. Sources:

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 WikiTree profile De Savoye-33 created by Schalk Pienaar, Jun 7, 2014. Source:

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 WikiTree profile De Savoye-5 created through the import of Margaretha Theresa DES AVOYE.ged on Apr 25, 2012 by Werner Schneeberger. (Included following note: 1 PROP Vrede-en-lust, Drakenstein 2 DATE 1688) Source:

- Title: Suid-Afrikaanse Geslagsregisters Volume 10 p. 633 (Abbreviation: SAG Vol. 10 Author: GISA)

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 WikiTree profile De Savoye-19 created through the import of Vermaak Family Site - 05 May 2013.GED on May 5, 2013 by Dina Vermaak. Sources:

- Author: Serge Meunier Title: Meunier Web Site Text: MyHeritage.com family tree

- Author: Paul Mare Title: Mare/Maree Family in South Africa Text: MyHeritage.com family tree Family site: Mare/Maree Family in South Africa

- Author: Lionel Thomas Title: Lionel Thomas Family Text: MyHeritage.com family tree

- Author: Paul Mare Title: Mare/Maree Family in South Africa Text: MyHeritage.com family tree Family site: Mare/Maree Family in South Africa

- ↑ Added by Evan Snyman 13 September 2014. Source:

- ↑ Source: First Fifty Years - Project collating Cape of Good Hope records Facebook Community Page: Timeline (2014) December 18, 2014 Seen and added by Philip van der Walt Jul 17, 2015.

- ↑ Entered by Pieter Meyer 25 April, 2013. Source: Colin Graham Botha, The French Refugees at the Cape (Cape Town: Cape Times Limited, 1921), p. 74. Also see Geni.com > French Huguenots who emigrated to South Africa.

- ↑ Also see: Robertson, Delia. The First Fifty Years Project. http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/ Page: Adam Tas & Adam Tas, Dagboek (eds. Leo Fouché, A.J. Böeseken, vert. J.P. Smuts). Van Riebeeck-Vereniging, Kaapstad 1970 2011 dbnl / erven Leo Fouché / A.J. Böeseken / J. Smuts. Seen and entered by Philip van der Walt Apr 3, 2017.

- ↑ Willem Adriaan van der stel succeeded his father, Simon van der Stel, as Governor of the Cape in 1699; Willem van der Stel abused his official position to corner an over-supplied market in farm produce. Van der Stel was jealous of Adam Tas's wealth and easy going life, and in 1706 he used his legal powers to arrest and imprison him. Tas became a Stellenbosch legend when he had this petition drawn up against incumbent Governor W.A. van der Stel and other farming officials. Tas and his fellow free burghers were protesting against the corruption and extravagant lifestyle of Van der Stel and the fact that abuse of power by officials led to unfair competition with burghers. The Tas petition was submitted to the Lords Seventeen, the governing body of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), in Amsterdam. The petition was rejected and on Sunday, 28 February 1706 Magistrate Starrenburg arrested Adam Tas. From documents in the desk of Tas, Van der Stel established the nature of complaints against him and also the names of the dissatisfied burghers. Though several more burghers were arrested and punished, they were victorious at the end, when the Lords Seventeen in October 1706 categorically prohibited officials to own land or to trade. His wife Elizabeth van Brakel tried hard to get him released; when Adam Tas was finally freed after thirteen months, he named his farm 'Libertas' (liberty). Van der Stel was recalled to the Netherlands in 1707. Sources: http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/adam-tas-arrested; http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/SOUTH-AFRICA/2005-05/1116668205 (seen and added by Philip van der Walt with the kind help of Maria Labuschagne on Apr 3, 2017.)

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 13.22 13.23 13.24 13.25 13.26 13.27 13.28 Added by Schalk Pienaar, 18 May 2014.

- ↑ See: Persecution of Huguenots Entered by Philip van der Walt July 6, 2014.

- ↑ Added by Schalk Pienaar April 18, 2014. Source:

- Botha, C Graham: The French Refugees at the Cape, 2nd Ed 1921.:

- Namen van de fransche gereformeerde vluchtelinge toe gestaen op het reglement en Eedt als vrije luijde te vertrecken naer de Cabo de bonne Esperance met het schip Oosterlant :

- Jacques de Savoije van Aeth

- Maria Magdalena le Clerck van tournay syn huijsvrouw

- Anthonette Carnoij van tournay : de schoonmoeder van Jacques d'Savoije.

- barbere out 15 jaren } Alle kinderen van Jaecques de Savoije

- Jacques out 9 maenden

- En hebbe alle dese voorenstaende mans persoonen gedaen den Eedt in hande van de heer galernis tresel als schepe binnen deser stadt Middelb. op de 8 Januar

- Jacques de Savoije van Aeth

- Namen van de fransche gereformeerde vluchtelinge toe gestaen op het reglement en Eedt als vrije luijde te vertrecken naer de Cabo de bonne Esperance met het schip Oosterlant :

- ↑ Ships Carrying Huguenots to South Africa:

- Ships Passenger List for Huguenot Ship Oosterland to South Africa 1688: "Belonged to the Chamber of Zeeland. Captain Carel van Marseveen. Left Middelburg on 29 January 1688, and Goeree on 3 February 1688. Arrived at the Cape on 26 April, 1688." [Among the passengers noted]

- * Jacques de Savoye (1636-1717) and Marie-Madeleine le Clercq (abt 1660-1721); * Antoinette Carnoy (abt 1630-?); * Marguerite-Thérèse de Savoye 1672-aft 1713); * Barbere-Thérèse de Savoye (1674-aft 1713); * Jacques de Savoye (1687-bef.1708); * Daniel Nourtier (abt. 1667-1711) and Marie Vitu (abt 1668-1711); * Jacques Nourtier (1669-1743); * Jean Nourtier (1671- aft. 1694); * Jean Prieur du Plessis (1638-1737) and Marie Menanteau (abt 1662-aft 1693); * Carl Prieur du Plessis (1688-1737) (born at sea); * Isaac Taillefert (abt 1651-1699) and Suzanne Briet (abt 1653-aft.1711); * Isabeau Taillefert (1673-1735); * Jean Taillefert (1676-aft.1708); * Isaac Taillefert (1680-1689); * Pierre Taillefert (1682-1726); * Suzanne Taillefert (1685-1724); * Marie Taillefert (1687-1689); * Jean Cloudon (?- aft. 1700); * Jean Pariset (1667-aft.1707); * Jean du Nus (1672-aft.1712); * Sara Avice (?-1688); * Jacques Therond (1688-1739)

- Sources: mostly Appendix 2 of "Hugenotebloed in ons are" by J.G. le Roux (1992; ISBN 0-7969-0566-5) and "French speakers at the Cape" by M. Boucher (1981, ISBN 0-86981-222-X) Contributor Lesley Robertson, Source: www.olivetreegenealogy Ships Passenger Lists seen July 16, 2014. Entered by Philip van der Walt.

- Ships Passenger List for Huguenot Ship Oosterland to South Africa 1688: "Belonged to the Chamber of Zeeland. Captain Carel van Marseveen. Left Middelburg on 29 January 1688, and Goeree on 3 February 1688. Arrived at the Cape on 26 April, 1688." [Among the passengers noted]

- ↑ The Rhineland measure was usually adopted in surveying land. It was approximately three times the size of the equivalent Dutch measure.[citation needed]

- ↑ The seal of the VOC used on documents at the Cape was a representation of the ship Dromedaris in which Van Riebeeck voyaged to the Cape.[citation needed]

- ↑ Translation of the original title deed of Vreede en Lust, a farm in the District of Drakenstein, April 1694. Granted in 1688 to the Huguenot Jacobus de Savoijen.[citation needed]

- ↑ Kolbe, Naaukeurige en Uitvoerige Beschryving van De Kaap de Goede Hoop http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/29363#/summary [citation needed]

- ↑ Hartdegen, Paddy (1988). Our Building Heritage – An Illustrated History. Halfway House: Ryll’s Publishing Company. p 12.

- ↑ Philip van der Walt July 9, 2014.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/g5/p5156.htm ( Schalk Pienaar, Jun 6 2014).

- ↑ See: Persecution of the Huguenots Philip van der Walt July 6, 2014

- ↑ G.C. DE WET

It may be possible to confirm family relationships with Jacques by comparing test results with other carriers of his Y-chromosome or his mother's mitochondrial DNA. However, there are no known yDNA or mtDNA test-takers in his direct paternal or maternal line. It is likely that these autosomal DNA test-takers will share some percentage of DNA with Jacques:

-

~0.39%

Letitia Botha

:

23andMe, GEDmatch EZ6728393 [compare]

:

23andMe, GEDmatch EZ6728393 [compare]

Have you taken a DNA test? If so, login to add it. If not, see our friends at Ancestry DNA.

Rejected matches › Jacques de Savoye (bef.1687-bef.1708)

Featured National Park champion connections: Jacques is 17 degrees from Theodore Roosevelt, 8 degrees from Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, 18 degrees from George Catlin, 20 degrees from Marjory Douglas, 26 degrees from Sueko Embrey, 18 degrees from George Grinnell, 18 degrees from Anton Kröller, 21 degrees from Stephen Mather, 21 degrees from Kara McKean, 21 degrees from John Muir, 15 degrees from Victoria Hanover and 29 degrees from Charles Young on our single family tree. Login to find your connection.

D > de Savoye | D > de Savoije > Jacques (de Savoye) de Savoije

Categories: Cape of Good Hope Stamouer-Progenitor | Cape of Good Hope Project Needs Validation | Huguenot Migration | Huguenot Emigrants

Le 29 aoust 1694 Philippe Rodolf fils de monsieur jacqes de Savoye Et madame le clair, le temoins Et Rodolf passemant Et sa famme -

The 29 August 1694, Philippe Rodolf son of Monsieur Jacqes de Savoye and Madame le Clair. The witnesses: Rodolf Passeman and his wife

Please merge De Savoye-70 into De Savoye-15